Why I'm leaving New York

And what it means to come home

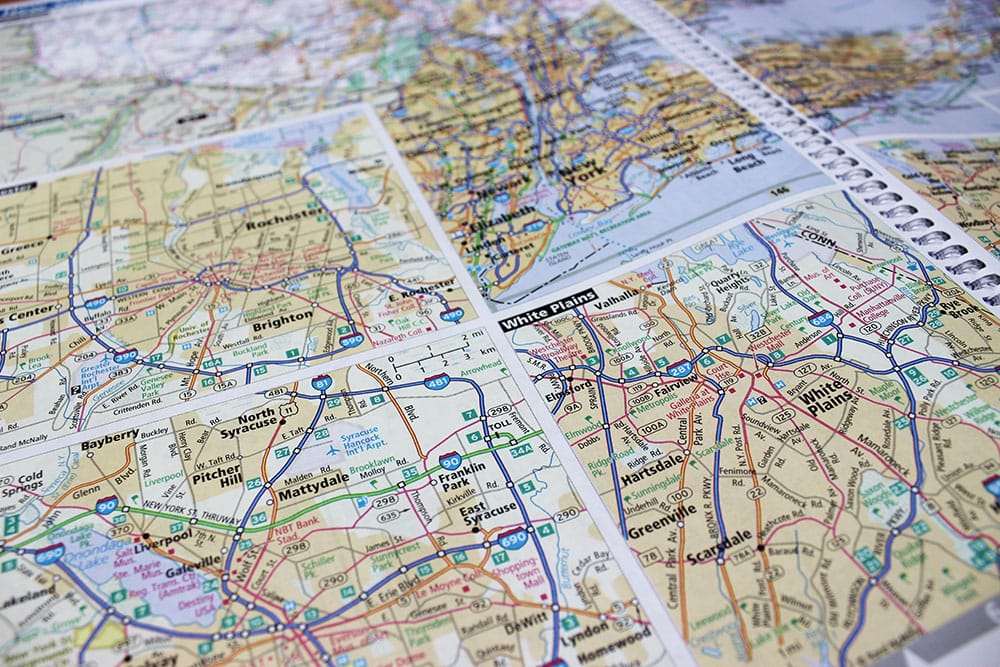

When I was a child and well on in to adulthood, I loved to look at maps.

I especially loved to look at US road atlases, those oversized Rand-McNally tomes that I would pore over in the backseat on long car trips. Down along the backroads of the US, I would wonder who I might be if I had lived in Alaska or Colorado or Vermont. What life might I have led? What person might I have been?

I was drawn to the remote places. I would ponder northern Alaska, say, for long minutes, and the far northern stretches of Minnesota — the highway stretching north along the shore of Lake Superior beyond Duluth, for instance — was another place that particularly called to me. Somewhere there, I might finally figure things out and put myself together.

I always saw this yearning as a natural outgrowth of my adoption. When my biological mother was in the last few months of her pregnancy, she chose a few possible families for me to end up with if I were assigned male at birth and a few possible ones if I were assigned female at birth. It stood to reason that the fact that I ended up with my parents was some combination of destiny and happenstance. There were universes where I ended up with other families, it would stand to reason.

And that’s just the assigned male at birth version of me. The assigned female at birth version of me, thanks to the weird strictures of the agency that handled my adoption, would have been a little sister to a big brother, the child of an entirely different set of parents. This is to say: I owe the life I have, with all its privileges and pitfalls, almost entirely to being trans, something I’ve written about more here.

When I looked at a map, I lived in none of the places I saw there, but I lived in all of them, too. What I saw on a map was an endless ocean of possible lives. The life I led felt entirely arbitrary, like if I pushed hard enough at the edges of it, it would give way and lead to something different, more real.

I loved portal fantasy growing up because I half expected to open the door to my bedroom and find not Oz or Narnia but a nondescript home in suburban Boston, a sleepy bungalow on the Florida panhandle, a mountain cabin in Montana. Something was wrong, and I didn’t know where to start looking to fix it.

I graduated from college at the last possible moment when one could use a journalism degree to receive job offers. I spent my first year of employment working at a newspaper in Milwaukee as a temp (which was amazing), and when that job wrapped up, I applied to six or seven different papers around the country and got interviews at five of them.

Not only did I get interviews, but I was flown out to meet with staff members in person. Later, I received job offers from all five. I am not saying this to brag about my journalism skills — at the time, they were perfectly fine but no great shakes — but to say that the pre-housing crash 2000s were a wild time, and I owe almost all of my career to the accident of timing.

The newspapers were based in Omaha; Riverside, Calif.; suburban Chicago; Raleigh; and Duluth, Minn. I also desperately tried to get a job at the Bergen County Record in New Jersey, because a family member worked there and because that would put me in spitting distance of New York. Alas, by the time they got back to me, it was already too late. I had taken the job in Riverside, a decision that led me to my current life in Los Angeles. At the time, I surmised, correctly, that if I didn’t leave for LA or New York in my early 20s, I never would. And I knew, deep down, that I had to get to one of those two cities. My future was waiting for me there.

But the longer I worked in journalism, the more that it seemed like my life should have been in New York. So much of the media is based there that many of my friends worked there, and when I visited with more and more frequency over the years, it was with the uncanny sense I used to get looking at those road atlases. It was like my alternate life was a palimpsest that overlay the city, guiding me toward a life where things hadn’t gotten off-track somewhere along the line. I could feel the frequency, but I couldn’t see it.

I felt this most keenly in places like Brooklyn and Queens, the places I surely would have found an apartment had I gotten a job in the city in the 2000s somehow. Walking through them, I could see little bodegas and cafes that might have become my haunts, could see folks hanging out and chatting outside of their buildings who seemed like possible acquaintances or even friends. Los Angeles felt so boxed off and isolating to me, a collection of Skinner boxes masquerading as homes. New York felt more real to me on some intangible level. I was sure I belonged there.

I applied for jobs in New York here and there, once even getting fairly close with the Times itself. But I know now that the life I thought I could find elsewhere was never waiting for me, because it wasn’t waiting for me in a place but, rather, inside of myself. I’ve never lived in New York, but to finally get to a place where I could move forward with my life, I had to leave it — or at least the idea of it — all the same.

My friend and ward Sydney, a terrific reporter on trans issues, first bonded with me over how many shared interests we had as kids, in ways that felt weirdly eerie to me. One that particularly struck me was how we both had a deep and abiding love of geography, of staring at the map until we might feel it suck us into some new place. Sydney used that desire to travel the world, while I mostly daydreamed about it.

But the better I get to know Sydney — and the better I get to know trans people in general — the more I understand that this shared desire was about a very potent certainty that life was wrong, the world was wrong. There had to be something better somewhere else, if you could just push through reality to the other side. (Come to think of it, these are the themes that undergird The Matrix, one of the cornerstone works of trans cinema.)

Maybe Sydney came to terms with her transness in her 20s because she didn’t have an adoption excuse to fall back on when it came to longing for some other life. But I also know her well enough to know that she was probably just more stubborn than I when it came to running straight at the problem. She took the freeway; I took the weird little backroad.

But the weird thing about this is that once I finally came out, it really was like I had found my way into some portal fantasy. There were times when I would be at a gathering and meet a new person and feel an intense, shooting certainty in the back of my brain that this person was going to be extremely important to me, and they’ve almost always joined the ranks of my very best friends. It did feel a little like witchcraft, like I had cast a spell that caused parts of my old life to dissolve slowly but surely, replaced by something more stable and lasting. I hadn’t managed to find my way through the door to the life I was supposed to have led, but I kind of had all the same. With every new friendship I built, every new project I launched, it became harder and harder to believe there was this long interregnum when I knew something was up but couldn’t see any way to look at it straight on.

A trans woman who emailed me recently described this as being “guided by resonance.” She feels, she says, like she’s an animal guided by sonar, sending pings out to the deep black and slowly building a map of the life she’s meant to have. It really does feel like that palimpsest overlaying one reality. One day, you wake up in a new world. You just have to have the strength to listen to the sounds that will guide you to it. You have all the tools to find the path through the dark. You only need to trust them.

I was in New York recently to meet with the Vox Culture team, who include among them my very favorite people. I adore my team, and I adore my editor, whom I’ve worked with for almost five years now, one of the longest professional relationships of my life (and honestly one of the longest relationships of my life period, excluding familial ones). In the past, even as recently as last year, when I would go to New York, I would feel the familiar sensations unfurl inside of me, start to see that map of the life I was not leading where I had turned these streets into my own.

But one morning, after meeting some good friends in the further out reaches of Brooklyn, where people on a fixed income can still (barely) afford to live, I was walking back to the train that would carry me to my office, and I had an unfamiliar thought: I wanted to be home. Looking around me, at the old buildings turned into housing, at the numerous little storefronts heralding a wave of gentrification, I no longer felt like this was a life I had misplaced. Maybe I could have been happy there, but I had never actually lived there. As surely as my real life had faded in around me once I had the courage to say my true name, this old dream was crumbling.

To be trans sometimes feels like a fairy tale, like you’ve made a bargain with some old god. You will give him years and years of a false life, years that he will use for his own purpose, and then, you will reach the end of that bargain, and he will be forced to give you the life you were meant to lead. Maybe I will move to New York someday, but it will now be on my own terms and not an attempt to force my life to begin. I joined my life already in progress, and once I got there, amazing things began to happen.

That morning, walking through Brooklyn, I felt sad that I had to leave my dream of New York. But a continent away, my wife was sleeping in our warm bed. Our cats were gathered around her. I had friends in New York, yes, but my deepest friendships were increasingly in LA, because that’s what happens when you can actually engage with people on a level where you’re not a weird maze they have to solve to find the real you. My creative collaborators were there. My favorite restaurants and bars were there. My church was there, and my messy desk piled high with TV screeners was there. When I wasn’t looking, I had gotten my life back, and that life was in Los Angeles, which meant my home was there, too.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the parable of the wise man who built his house upon the rock, instead of the man who built his house upon the sand. The first saw his house stand firm amid the storms, while the latter saw his house crumble as the ground gave way beneath him.

The parable was always explained to me as being about faith — you cannot have good faith without a strong foundation. (To be fair to everybody who explained it to me this way, they can cite as their primary source Jesus Christ, who explains it similarly.) But a minister friend of mine told me that there are some strains of theology that say you cannot find God until you find home, which is to say that what’s important in the story is not the foundation but the house itself. Finding God is all well and good, but you have to have the right vessel to do it in.

Imagine, then, some earlier version of myself, looking at a map, maybe, or walking down a street in Brooklyn, and opening doors to other houses that blow away in the wind. And now, here I am, having found a house that stands firm against whatever I can throw at it. One day I opened a door and saw myself, wondering where I’d been, excited at long last to leave behind dreams and start living in a world where it rains and rains, but the walls don’t come tumbling down.

Annoying public service announcement: If you didn’t back the second season of my podcast Arden, you still can! Because we met our original funding goal, the curious can still purchase our various perks over the next several weeks. If you’re interested in trans stories, told by trans people, well, this season (with two trans writers in our room — including me, obviously — and several trans people in our cast) qualifies. We more than met our goal, but every little bit you can spare helps, and we have some cool perks, including the ability to make me review some dumb bullshit in this very newsletter!

What I’ve been up to: This week, I published two pieces I’m extremely proud of. One was an interview with Portrait of a Lady on Fire director Céline Sciamma, which inadvertently touched off a days-long discussion of when Leonardo DiCaprio got famous and how (don’t ask). The other was an examination of what it means to be a traditionally feminine trans woman, to mostly be a passing trans woman, and a whole bunch of other things. It’s a loose sequel to “The Catastrophist” (aka my coming out essay), and if you haven’t read it yet, well, I am really, really proud of it.

In the months thereafter, money seemingly poured out of me. It was so, so expensive to be a woman. I found myself having to buy an entirely new wardrobe, one I’m still struggling to fill out here and there. I needed new shoes. I needed makeup. Buying all this stuff in aggregate was expensive, of course, but each individual item was expensive in and of itself.

Can a man spend a lot of money on clothing? Of course. But he also has many affordable options. Finding such options in the women’s section was its own challenge. It was as if I was experiencing the market pressures of being a teen girl in the space of about three months instead of over several years.

Even beyond that, there’s the cost of laser hair removal and electrolysis to get rid of my facial hair. There are regular sessions with a therapist who specializes in gender dysphoria. There was a crash course in voice training, in an attempt to coax my old rumble into a reasonable alto. Changing my name cost almost $500, and a printout of the paperwork proving my name was changed was another $50. There are so many expenses to come, including surgeries and more documentation of my identity, and so on and so forth. It’s expensive and exhausting, and it will never end.

And yet I never ask myself why I’m doing all this. I just am. I need to.

Read me: Hey, don’t let us trans ladies have all the “telling stories about the trans experience” fun! Daniel Lavery’s new book, Something That May Shock and Discredit You (published under the name Daniel Mallory Ortberg) is one of my favorite books ever, ever written about realizing the extremely strange thing that you were assigned the wrong gender at birth and have to go about correcting that. Lavery writes so brilliantly about what it means to be a trans man. Read an excerpt in the New York Times, and check out my colleague Constance Grady’s review. You can also read some awesome interviews with Lavery!

The below is one of the best descriptions of being trans I’ve ever read, and now that I read it again (months after I first read it), I am realizing I just kind of wholesale ripped it off above, so let’s pretend I didn’t do that, huh? And as penance, buy Danny’s book.

One of the many advantages of a religious childhood is the variety of metaphors made available to describe untranslatable inner experiences. A few years later, with a transition slightly less bedcentered, I might have described that feeling instead as this: after a number of years being vaguely troubled by an inconsistent, inexplicable sense of homesickness, I woke up one morning and remembered my home address, having forgotten even that I forgot it in the first place, then grew fearful and weary at even the prospect of trying to get back. I have often had a relationship to men that has been bewildering to me. I have been sometimes too charged with an emotion I cannot name, and tried to get them to relate to me in a way that was not easily recognizable, either to them or to me. Had I been in any way prepared for that moment of question-asking, I would have arranged my life in such a way that the moment would have never come. I never saw it coming, so I was never ready; then it was over.

The timeline of awaiting a rapture is broken into two parts: First one becomes willing to be stolen away, then one waits patiently for it to happen, occasionally topping up one’s own willingness and preparedness if stores seem to be running low. But the forces of Heaven do the lifting, the heavy work, the spiriting away, the catching up of the body in the air. The timeline of transition is both alike and nothing like it: One becomes, if not willing to transition, at least curious, sometimes desperate, sometimes terrified, sometimes confident, sometimes tentative. Then, at some point, one has to do or say something in order to make it happen. The force of my desire to transition, when I allowed myself to be hit with the full force of it, felt so supernatural and overwhelming it felt as if all I had to do was stand and wait and somehow the process would begin itself around me, first the lifting, then the heavy work, then the catching up of the body in the air, then the translation from the corruptible to the incorruptible. My own desires had seemed external to me – I certainly couldn’t remember deciding to want anything – so it stood to reason that whatever came next would happen to me rather than because of me.

Watch me: A movie that, for me, captures the feeling of homesickness that Lavery alludes to above (and that I hint at as well) is the 2014 animated film Song of the Sea. The film has nothing to do with transness, except for all of the ways that people who shapeshift into animals — in this case selkies — are kind of trans-adjacent in folklore. It’s one of my very favorite movies, and it has such a particular late autumn melancholy that I can barely stand it.

And another thing… Here’s John Goodman singing the theme song to a Myst parody called Pyst. It is an incredibly weird bit of ‘90s video game ephemera, and I’m so thankful the Digital Antiquarian reminded me the game even existed.

This week’s reading music: “A Little Uncanny” by Conor Oberst

Episodes is published once per week and is about whatever I feel like that particular week. Suggest topics for future installments via email or on Twitter. Read more of my work at Vox