Why Hayao Miyazaki and David Lynch excel at dream logic

And very few of their imitators do

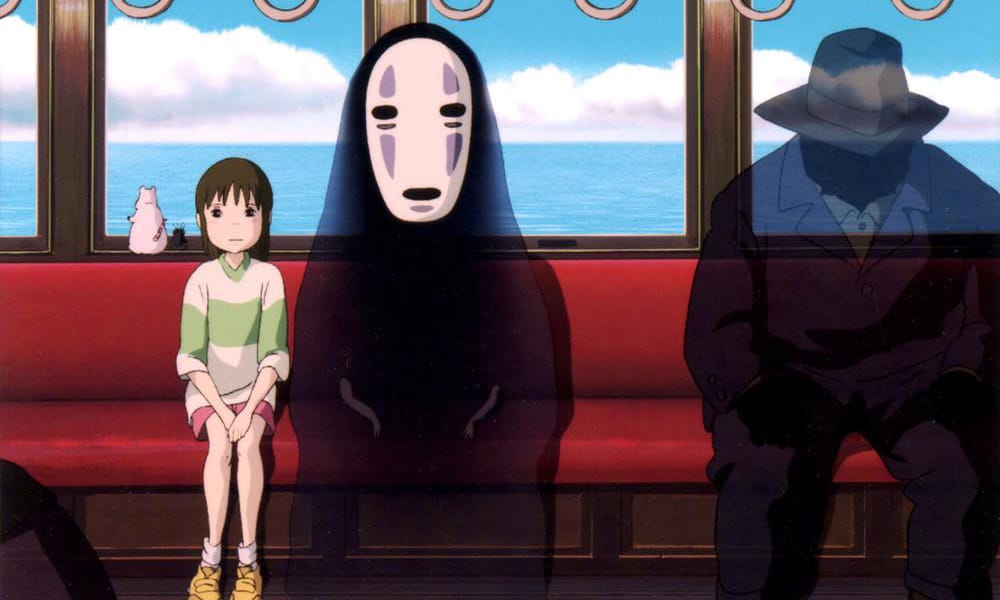

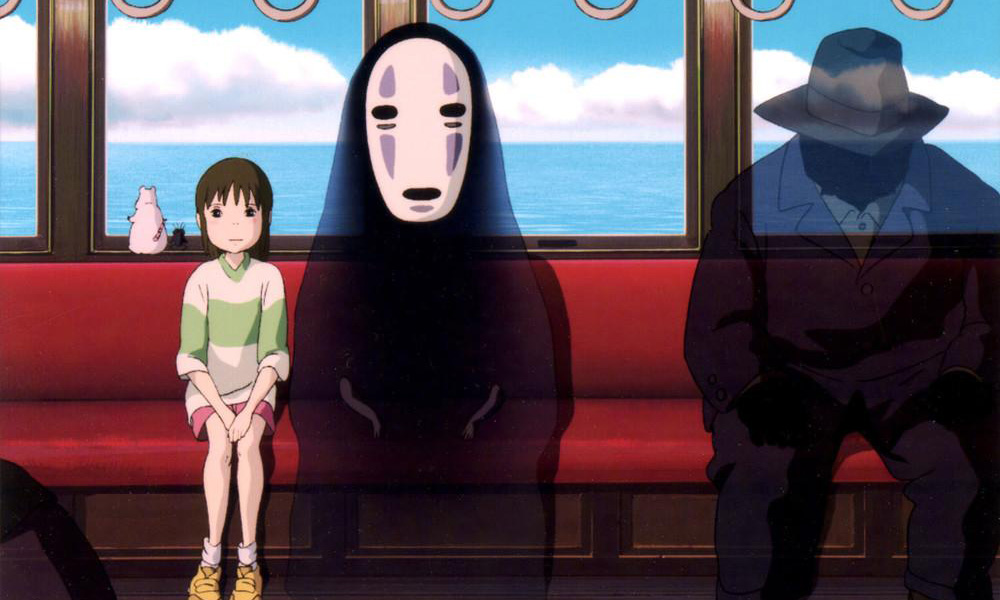

A few weeks ago, in the midst of a rotten day, I sat down to rewatch my favorite movie of all time, Spirited Away. The movie falls generally into one of my very favorite subgenres, the portal fantasy, and the character of Chihiro, a young girl who forgets her name and nearly becomes lost forever because of it, has personal resonances with me for some reason.

But what struck me on this time through the movie — which I’ve seen many times — was just how little time it bothers explaining anything that happens in it. Sure, if you know a ton about Japanese mythology and folklore, you will probably be able to parse the otherworldly rules and denizens of the strange spirit bathhouse Chihiro finds herself trapped in. But for the most part, the movie only tells you what you absolutely need to know. Everything else feels like it’s happening for reasons you can’t quite grasp.

This is true of many of Hayao Miyazaki’s films, of course. My other favorite of the director’s movies, My Neighbor Totoro, offers slightly more explanation for why two sisters start being visited by a forest spirit and his pals, but only slightly. When they ride on a giant catbus, you either find yourself nodding along in appreciation for the movie’s inventive whimsy, or you’re looking for the next exit.

Miyazaki’s work has often been held up as a marked contrast to films created for children in the United States, which tend to have fairly ironclad logic and rules that are explained over and over again. For as much as I enjoy the films of Pixar, for instance, the only time they start to approach the anything-goes feeling of Miyazaki’s work (for me, at least) is during certain portions of Ratatouille, when the film asks you to just go along with some of its most ridiculous conceits.

On this tour through Spirited Away, I found myself thinking of a wildly different project, at least on its surface: David Lynch and Mark Frost’s Twin Peaks: The Return. Like Spirited Away, Twin Peaks takes place in a world that we have to reach through some sort of portal, where nothing quite lines up with what we know to be true of reality. And like Spirited Away, Twin Peaks is directed by a man who knows how to create odd, dreamlike scenarios that stir something in our subconscious.

Naturally, there are numerous differences between the two artworks. For one thing, Twin Peaks is dark and challenging, intended for an audience that wants to have something enveloping and strange to watch, where Spirited Away is much more mainstream, to the degree that it’s still the highest grossing film of all time in Japan. And for another, Miyazaki’s dreamlike states take the form of whimsy, where Lynch’s are typically nightmarish. Miyazaki plumbs his subconscious and emerges with beautiful visions of other worlds; Lynch just finds dark nightmares.

But I still found myself thinking about why I’m so willing to go with Miyazaki and Lynch to dream states, where so many of the two’s imitators often seem to treat “Lynchian” as a synonym for “throw some weird shit at the wall.” Of course, Miyazaki and Lynch are highly talented directors, among the best alive today (and, indeed, of all time), which sets them apart from everybody who thinks copying Twin Peaks is an excuse to craft an elaborate mythology and center it on a small town. (RIP Happy Town.)

Here’s the best answer to why these two are so much better at this than others that I could come up with: Miyazaki and Lynch ground their dream states in rules, but they are not rules that we can comprehend. To tell you the truth, I’m not sure Miyazaki or Lynch could comprehend the rules either. They simply understand that in a dream, there’s always a vague sense that someone somewhere could make sense of what’s happening if you could just ask the right questions of the right person.

That need for rules that are never explained might also offer a hint as to why so many TV shows that aim for Lynchian eventually get consumed by full-on mythology. I love Lost, for instance, but there’s a distinct difference between its first three seasons, when the Island was dark and weird and hard to understand, and its last three, when the writers started trying to explain a lot of the weird shit going on on it. (It’s sort of impressive the degree to which they explained nearly everything without explaining it in a way that casual viewers could put together easily — it might be the best splitting of the difference between explanation and obfuscation in popular art that I’ve ever seen.)

The only TV show I think has come close to the sheer unsettling nature of Lynch or Miyazaki is probably The Leftovers, where the show gradually accumulated a rich body of lore that only somewhat made sense. And yet the lore did make sense to most viewers, because it was steeped in Judaism and Christianity, two religions that most Americans have at least a passing familiarity with.

The reason The Leftovers excels at weirdness might also explain why Lynch and Miyazaki excel at weirdness. They, too, are drawing from rich religious traditions. Lynch has spoken often about the ways that transcendental meditation has influenced the ways he tells stories, and if you really try hard enough, you can tie most of the spirits in Miyazaki’s films to Japanese folklore. But importantly, none of these stories have a sequence where someone sits down and explains the rules of what’s happening. The characters simply find themselves in a scenario that feels like it should make sense but doesn’t, ultimately.

Lots and lots of uncanny stories (horror, fantasy, sci-fi, etc.) take place in worlds that have iron-clad, rock-solid rules which some character or another explains fairly early on. This technique is great, especially when it works well. But goodness me do I prefer when there’s a story that is grounded in some sort of logic that I can never quite parse, because that logic is being held for me by others far more powerful and wise, who live in a temple I can never access. The thing about “dream logic” is that it’s still logic; we’re just not privy to its secrets. And to me, that’s always going to be more compelling than knowing exactly why the thing does the thing and how to stop it.

Programming note: Hey, everybody! I’m thinking of adding a paid tier to this newsletter, because with the slow strangulation of culture freelancing outlets, I’m seeing a dearth of the kind of writing I love to read. With enough paid subscribers, I could ideally pay for the writing and editing of one new freelance piece every week, usually on Wednesdays. Then I’d probably run a TV recap on Friday, time permitting. (The Monday edition of the newsletter will always be free.) Let me know if this is something you might be interested in!

What I’ve been up to: It’s been two weeks since there was a new newsletter. (I was on vacation last week!) And I didn’t run any of the usual segments in the last newsletter before break, because that was a short story! So it’s been a while since we checked in on what’s up with me. In that time, the piece I’m proudest of running was this story on the incredibly boring aesthetics of the Republican National Convention, which was a real drudge of a convention.

Read me: Speaking of stories where there are rules somewhere that the reader is not privy to, Tamsyn Muir’s Gideon the Ninth (which everybody I know read last year and which I am just getting to now) is a tremendously effective version of a story where it’s clear there are rules, and we’re probably going to find them out at some point, but until then, everything is weird and strange and wrong. It’s terrific science fantasy, and you should read it! I ship Gideon and Harrowhark! I don’t care what you think!

Watch me: I always love Dan Olson’s work, but his new video, In Search of a Flat Earth, is really something else. It starts out debunking flat earth theories, then quickly pivots to pondering the psychological need for flat earth theories, then takes an amazing twist halfway through that made me think in new ways about things that deeply concern me. Watch it!

And another thing… I’m not saying one of you needs to make me a Wikipedia page, but I wouldn’t say no to a Wikipedia page…

This week’s reading music: “Your Belgian Things” by The Mountain Goats

Episodes is published once per week and is about whatever I feel like that particular week. Suggest topics for future installments via email or on Twitter. Read more of my work at Vox