When did network television dominance end?

I have an answer to this question: on November 22, 1998

When I first started paying attention to TV critically in the early 1990s, the assumption was that the pinnacle of the form was to have a show that was successful either creatively or commercially on network television. The handful of shows that threaded the needle to land at the center of that Venn diagram intersection were the series that came to dominate discussion of the medium. Think of All in the Family or Cheers or ER.

Creating something successful within the constraints of network TV was hard enough. Creating something that actually made an artistic statement worth celebrating was rarer still. And creating something that satisfied both of those demands was the rarest bird of all. Creating a show that hit that bullseye essentially meant that the creator was set for life. Matt Groening need never do anything again, because The Simpsons has made him so rich that he retitled Life in Hell to Life Is Swell in 2007, because he thought things were just peachy in that, the year the global economy began to collapse.

But from 1950 to the late 1990s, TV coverage tended to focus on network TV as the main place where the artistic boundaries of US television were being stretched. It's easy to forget now, given what came after, but the 1990s were subject to a handful of stories insisting that TV was suddenly better than the movies. The shows listed in those articles mostly aired on one of the broadcast networks of that era: ABC, CBS, Fox, NBC, UPN, and The WB. A cable show or two (or a cable movie) would sneak onto these lists. (This was, after all, the era of The Larry Sanders Show on HBO.) And PBS certainly made a few buzzy programs at the time. But the shows both TV fans and TV critics talked about were all on network TV.

This era came to an abrupt halt on January 10, 1999, when The Sopranos aired its first episode on HBO. The series wasn't the cable network's first original drama. But Oz, to pick one pre-Sopranos HBO drama, never quite hit the next level, not because it was lackluster (it was quite good!) but because its storytelling approach was so aggressive that it turned off lots and lots of viewers.

The Sopranos is by no means a comforting watch, but it gives you the pressure release valves of artistically satisfying TV shows that also become commercially successful. It had comic relief characters and a high-concept premise. (It's easy to forget now, but in 1999, most of the marketing centered on a mobster walking into a psychiatrist's office.) It had a compelling main character who did larger-than-life things (like kill people) while remaining understandable to the audience. Each episode was satisfying individually, while all of them added up to a season-long whole. And, most importantly, it was readily possible for TV viewers to read themselves into Tony Soprano's world. You could identify with Paulie or Carmela or, hell, Father Phil. Their life was more glamorous than yours, but you could see yourself there.

The Sopranos wasn't an immediate sensation commercially. (It was critically, as you probably know.) But by the end of its first season, it had become appointment television for a growing number of people, and in its second season, it started to blow up. And the show's growing centrality to the TV conversation was inextricably tied to its presence on pay cable. The qualities that made The Sopranos memorable were things you just couldn't do on network TV. Tony Sopranos anti-heroics would have been network noted to death, and, needless to say, the show's language, violence, and sex weren't going to fly even on Fox, restricted as the broadcast networks were by the FCC.

(Sidebar: Not everybody knows this, but cable networks are not regulated by the FCC at all. That's why networks like FX, USA, and Syfy started allowing unbleeped utterances of "fuck" a few years back, without so much as a peep from most viewers. There is, in theory, nothing stopping Nickelodeon from becoming a raunch fest, though that would probably get the channel dropped from most cable packages.)

So if we accept that the debut of The Sopranos was the first real blow against network TV's dominance among TV fans and the TV press, then there has to be a last moment of network TV swagger, right? And could we pinpoint it?

We sure could.

For much of the late '90s, TV conversation centered on two network TV lineups: NBC's Thursday night lineup and Fox's Sunday night lineup. If you were adventurous, you might also include The WB's Tuesdays, but enough people thought Dawson's Creek was kinda crappy that it wasn't quite at the same level. (Those people, by the way, were right.)

But in the 1998-99 TV season (aka the one we're talking about here), both of those lineups saw major pieces of their dominance go missing. NBC was grappling with the end of Seinfeld and the move of Frasier to Seinfeld's old timeslot (a mistake, I think), while Fox had voluntarily shuttled a creatively peaking King of the Hill off to Tuesdays in favor of That '70s Show.

What's more, of the shows left behind that had made these lineups so dominant, only Friends was really at its best. The show's fifth season aired in the 1998-99 TV season and was probably its best season. From Frasier to ER to The Simpsons to The X-Files, both lineups boasted plenty of shows that were still good but past their creative peaks. And yet all of these shows still garnered lots of press attention, especially when they did a big, buzzy episode.

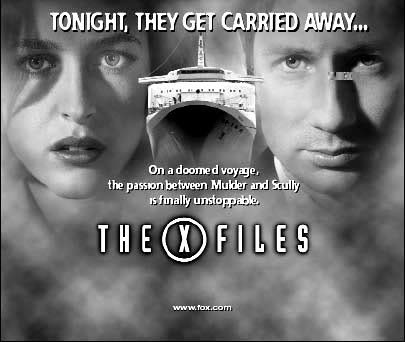

A big, buzzy episode like "Triangle," the third episode of The X-Files' sixth season.

In late 1998, The X-Files was still probably the hottest thing on TV. It had gone from a cool, cult hit that was hip to say was your favorite show on TV to genuine phenomenon, and in the summer of 1998, the first X-Files movie came out. But that movie didn't really push the show to a new level, and its sixth season would be defined by the series casting about for something new to do with itself. (I like the sixth season, but it's nowhere near the series at its best.) What's more, that sixth season saw the show's production move to Los Angeles, a move that deeply affected the look and feel of the series.

Still, the show was more than capable of generating headlines, and "Triangle," an episode edited to seem like it had been shot in a few very long takes, following Mulder and Scully as the former investigated a ghost ship in the Bermuda Triangle and the latter tried to track down her partner yet again, was exactly the sort of thing TV critics and reporters were happy to hype endlessly. "Triangle" isn't the last great episode of The X-Files' original run (honestly, that's probably the penultimate episode of the whole series, "Sunshine Days"), but it's probably the last time the show was able to effortlessly generate huge amounts of hype for itself.

And it's a really good, really fun episode! I watch it again every few years, and I always find it to be a hoot. What's more, it's a fun episode you can watch without having to excuse the show's weird tendency to insert rape storylines into its comedic episodes. "Triangle" is pure pulp adventure, complete with Mulder decking Nazis in the 1940s, all of the show's major players popping up as different characters, and a swing music score that really deserved an Emmy. It's a blast, and if it was the end of The X-Files' dominance as a TV show everybody talked about, it was a good way to go out.

In the book Monsters of the Week: The Complete Critical Companion to The X-Files (available wherever books are sold!), genius TV critic Emily VanDerWerff writes:

To watch "Triangle" now is to remember a time when this was the most daring show on television. It's not deep in the sense of making grand philosophical statements, but it's fizzy and fun and invested in the idea of Mulder and Scully as two halves of a perfect duo. Maybe, then, this is the show at its best. Once there was a show that attempted big, bold things like this, and it was beautiful.

(When it came time to pick the image that would illustrate the season six section of the book, my co-author Zack Handlen and I picked an image from "Triangle," of Scully and her alternate self from a different timeline, seeming to look over their shoulders at each other as they pass. It's one of my favorite images in the whole series.)

"Triangle" isn't the best episode of its series or the TV season it aired in (that, indisputably, is "College," the sixth episode of The Sopranos). But it's the last gasp of a model nobody realized was about to change irrevocably. In early 1999, the brightest TV talents would be drawn, more and more, to cable and later to streaming, and network TV, which is still where the most money can be made, slowly became an unfortunate afterthought.

It is mostly an accident of timing that "Triangle" holds the position it does. "The One with All the Thanksgivings," a.k.a. the Friends episode where Joey gets a turkey stuck on his head, aired just three nights earlier and has probably had a longer tail as a cultural reference point. And a bunch of huge, beloved episodes of other shows aired in early 1999 on network TV, episodes like ER's "The Storm," or Buffy the Vampire Slayer's "Graduation Day" two-parter, or even The X-Files own "Two Fathers" and "One Son" two-parter, which purported to solve the show's overarching mystery about the alien conspiracy. But once The Sopranos debuted, the conversation started to shift rapidly.

Network TV put up a fight for most of the ensuing decade. The West Wing debuted in the fall of 1999 and became a massive success with viewers and with critics, and network TV was home to a bunch of groundbreaking shows in the 2000s from Lost to Malcolm in the Middle to 24. But the network TV barrel had sprung a leak, and no matter how frantically water was shoveled back into it, it was going to drain out eventually.

It's impossible to say what was the very last network TV moment everybody had to watch, because you could argue that as recently as a few weeks ago, CBS's airing of the Oprah Winfrey interview of Harry and Meghan was a must-watch. But if we're looking specifically at scripted programming, it's probably the final episode of Lost in 2010. (Ironically, one of the closest shows since then on network was the first episode of the X-Files revival.) You could also argue for a handful of comedy episodes (in general, network TV comedy held out way longer than network TV drama) or a couple of reality finales, but even there, cable was racing ahead.

In terms of creative strength, The Sopranos gave cable a leg up over broadcast, which it then began using to take huge leaps forward, with shows like The Wire or Deadwood or even Nip/Tuck. These were shows network TV simply couldn't do, for one reason or another, and they were far more likely to drive conversation. And the conversation pivoted accordingly.

I'm not writing this to damn network TV either. I honestly think a healthy broadcast network economy is one of the best ways to keep TV from losing what makes it as good as it can be. The folks who created the great dramas of the so-called golden age of television all did so after having worked in the network TV trenches, and I would almost always rather watch random reruns of a mid-level network show from the '80s or '90s than some of the formless streaming junk that gets on the air today.

But it's hard to miss the ways in which network TV began to feel like it wasn't at the forefront of the medium anymore after The Sopranos debuted. It was a slow process, until, all at once, it seemed like the creative spark had moved elsewhere. There are still terrific shows on network TV right now (like the very X-Files-y Evil on CBS), and you never know if a network will suddenly air TV's hot new thing. But the odds are much longer than they've ever been.

I remember watching "Triangle" the night it aired. I remember being hyped for it. I remember loving the episode but also feeling a bit like I had seen everything The X-Files, long my favorite show, had to offer. I wondered if anything else was on. And a few weeks later, I had my answer.

Talk back to me: What's the last network TV show you remember really being into? Where you just couldn't miss an episode?

And also let me know how you feel about Letterdrop! I'm still figuring out the CMS here, but I like it for the most part! (By the way, subscriptions should be back on in a couple of days! Just waiting on one last piece of housekeeping from Substack.)

What I've been up to: It's been so long since I did a Monday newsletter that I have a whole bunch of new articles over at Vox for you to check out if you haven't. Of them, I'm probably most proud of this piece on the ways in which our conversation about trans lives is completely and utterly broken by pointless questions that ignore the real issue.

Those who question the stories of trans people — especially trans youth — rob us of our autonomy to define our lives. They argue, sometimes implicitly and sometimes explicitly, that cis people are the true arbiters of who we are. They suggest that when trans people advocate for our interests, both as individuals and as a community, we are being selfish, naïve, and uncompromising. But it is not selfish to say you have a self, it is not naïve to believe that you know that self better than others, and it is not uncompromising to insist that you should live a life of dignity the same as anybody else.

Every day that cis people guide most of the conversations about trans people is a day that further suggests our lives are not worth living as they are. But if our lives are what we say they are, and if they are not worth living as they are, what are you trying to tell us? Where would you have us go? Answer that question. I’m waiting.

Read me: There have been a host of really great "why I'm leaving Substack" pieces in the last few weeks, including this one and this one, but I really appreciate Dan O'Sullivan's farewell for its wide-ranging sweep of references to other works and for the phrase "intellectual scab":

I’ve developed a theory of such a figure; they’re what I call “the intellectual scab.” While writers of conscience would never stoop to defend quack doctors attempting conversion therapy on trans kids, for the intellectual scab, it’s an opportunity. Like all scabs, the more integrity others show, the more there is to gain from doing what they won’t. Only in this case, the scab isn’t being called in to dig coal or repair phone lines; as intellectual scabs, their job is to peddle the basest, most vile ideas, the ones those writers with self-respect and brains and talent and conscience are picketing. Short-term, they take home a fat pay packet, with some ready-made branding baked in: they are mavericks for “just asking questions,” it never occurring to their dopey followers that the questions might already have answers.

Watch me: I am by no means a Friends superfan, but this little compilation of the various characters finding out Chandler and Monica are together is a nice reminder of how solid it could be at finding perfect sitcom rhythms. And it's also a reminder of how the Chandler and Monica relationship was a terrific throughline for the first third of its fifth (and, again, best) season.

And another thing... I tried to go meatless as often as possible in March, and while I didn't go 100 percent meatless, I did find some great new recipes I'm going to be using again and again. This salt and pepper tofu recipe is, honestly, one of my favorite things I've made ever. Try it out!

Also just watch this. Trust me.

Opening credits sequence of the week: This credits sequence for the show Charlie & Company seems to be for a largely typical family sitcom, starring Flip Wilson and Gladys Knight, as well as a young Jaleel White. But then, we head to the main character's office, and an endless parade of indistinguishable coworkers appear before us. This show only lasted one season, and it still wrote out all those coworkers before it ended!

A thing I had to look up: I spent a lot of time trying to figure out just how much buzz the Friends episodes that aired between "Triangle" and the Sopranos pilot garnered, but after a busy November sweeps for the show that year, it took it easy for a bit in December and January, just long enough to stay off the hype radar.

This week's reading music: "Ringside" by Julien Baker

Episodes is published three times per week. Mondays feature my thoughts on assorted topics. Wednesdays offer pop culture thoughts from freelance writers. Fridays are TV recaps written by myself. The Wednesday and Friday editions are only available to subscribers. Suggest topics for future installments via email or on Twitter. Read more of my work at Vox.