What I learned about my trauma from a deeply trans video game

By Lily Osler

(Welcome to the Wednesday newsletter! Each week, I’m publishing a new pop culture essay from a freelancer. Remember: Your subscription fee helps me pay these freelancers for their efforts! This week: Lily Osler, on the ways that the video game Celeste explores a tricky, hard-to-talk-about aspect of trans identities.)

The beginning of Celeste sees Madeline arrive at the mountain trail.

Honestly, I hadn’t even considered playing Celeste until it came out that its protagonist was trans.

I’d heard plenty about the video game before then. I don’t play many games myself, but I’m a trans woman, so most of my friends do. I’d heard them talk about how meaningful and moving and intensely fun they found Celeste. From what I could gather, it was an 8-bit platformer — think Super Mario Bros. — famous both for telling a moving story about depression and trauma and for its brutally hard gameplay.

I was a kid in the 2000s, so 8-bit/16-bit style games play off a nostalgia for a time I didn’t live through and, thus, have never held much appeal for me. The supposedly punishing difficulty level scared me off, too. I’m not even very good at the few games that I do play.

Then in November 2020, Maddy Thorson, the game’s creator, published a blog post explaining that the game’s protagonist, Madeline, is canonically a trans woman. There’d been hints this was the case. Madeline had a trans pride flag in her bedroom in a late cutscene, and the development team had a number of trans people on it, including Thorson themself. But once the blog post went live, the transfemme communities I’m in lit up with excitement. There were dozens of messages from people who’d played the game before and saw new and profound meaning in it with the knowledge that Madeline is a trans girl.

That revelation was what spurred me to buy Celeste. I’m constantly starved for good depictions of trans women in media, especially ones that center the complicated ways we live out our transness, instead of privileging the cis gaze. And I’d heard that Madeline was supposed to be in her young to mid twenties and to have transitioned recently, a demographic I’m in and one that’s almost never explored in popular media about trans people.

In Celeste, the player controls Madeline, a young woman whose backstory is more alluded to than explained. She’s climbing the game’s titular (and surprisingly real) mountain mostly just to prove to herself that she can. She’s recently had what’s strongly implied to be a mental health crisis that dredged up a lot of long-buried traumatic memories. She struggles with anxious episodes, intrusive self-critical thoughts, and panic attacks. Throughout her climb, she’s haunted by a ghostly, red-eyed version of herself who is trying to get her to give up and go back down the mountain. The game’s resolution comes when Madeline realizes that the part of herself that’s trying to sabotage her is terrified and deeply wounded, and that the only way forward in her life is to forgive herself for feeling that pain.

The gameplay mirrors Madeline’s mental health journey in a way that I found striking. The game is very hard, but the difficulty isn’t there to gatekeep; it’s to familiarize the player with failing and trying again, which they will do often. In each of the game’s chapters I died somewhere between 400 and 1,000 times, which I’m told is typical for people who aren’t extremely into hardcore platformers. But the game doesn’t punish you for losing; in fact, it wants you to win. Its controls and level design mean that every time you try and fail, you get a little closer to the end of the level. As you go on, you learn how to understand the game’s environments and how to refine your controls. But mostly, you learn how to be okay with failing and picking yourself up and trying again.

My friend (and this newsletter’s editor) Emily VanDerWerff has a metaphor she uses when she’s talking about the way trans people repersonalize, (the process of coming back into our own minds and bodies after years and sometimes decades of dysphoric dissociation, after we’ve spent a good amount of time living as ourselves).

Unless we had the (very rare) privilege of living completely trauma-free lives before we transition, year one of transitioning is a lot like finally ripping out some old, dusty, hideous shag carpeting from a room, and year two is like realizing, once it’s all torn up, that the floorboards are rotten beneath. You could have easily fallen through at any time before now, and it’s a miracle you didn’t. On the whole, it’s a good thing to know that the rot is there so that you can go in and fix it. But God, it’s terrifying to see it all laid out like that, gray-black and soft and oozing. And it’s going to take forever to fix.

For many trans people, before we transition, our ability to understand ourselves and our lives clearly is impeded by the way dysphoria muffles and nearly suffocates everything it touches. For those of us who medically transition, that first year on hormones — when your brain is finally working the way it should, your body begins to feel like your own, and you develop the strange feeling that you are at last a person — is euphoric. But soon you turn your newfound sense of agency and personhood toward your past. The floorboards, which you’d never once thought about with all that horrible carpet on top of them, are rotten all the way through.

For some trans people, this is an immediate and jarring realization. For me, it was gradual. I went from saying I had a happy childhood to saying I had a fine one to saying I had a rough one but it was okay because it was all behind me now. It was only once reams of horrible childhood memories had already come back that I finally, weakly admitted to myself that yes, I was carrying some trauma.

Yes, those horrible stories I always ended with “but it’s fine” were never actually fine, not when I was living through them and certainly not when I was telling you them, eyes averted, feigning impartiality and distance.

Yes, when I have to go to the bathroom at a party and you hear me hyperventilating and ask if I’m okay, and I moan that you shouldn’t worry about me, that means someone said something that triggered memories of that trauma, and I am currently lying in the tub and having a panic attack.

Yes, I’m terrified. Yes, I’m trying to work through it, but every time I think I’ve processed everything, a whole new batch of realizations, worse than before, come into focus.

Yes, this is hard. Yes, this fucking sucks. Yes, I have no idea what to do.

There are many ways to read Celeste’s story. You could certainly read the game as a metaphor for coming to self-acceptance and transitioning. Others read it as a game about anxiety and depression where the trans themes are at best incidental.

It makes most sense to me, though, as a game about the painful process of repersonalization. Madeline has been transitioning long enough for everyone she meets to effortlessly gender her female, and her identity as a woman is never in question. But she does still have what seem like painful dysphoria symptoms and is clearly anxious about her appearance, cowering from unexpected photos and finding the dark, distrustful part of herself lurking inside a mirror.

More to the point, she’s coping with what is strongly implied to be an estrangement from a once-close loved one. She alludes constantly to “things that happened to me a long time ago” that she “should be over” but which are nonetheless cropping up in her memory with a newfound urgency. She grapples with self-doubt born from deep pain, a fear of confronting her past, and an instinct to try and cover up the floorboards again. She’s so angry, yet can’t bear to turn that anger on anyone but herself. She is finally living as herself. She has to find a way to deal with the things her dysphoria had been covering up.

I bought Celeste during one of the worst weeks of panic attacks I’ve had in a long time. I was finally taking steps to deal with the root cause of the trauma. That work was important but unbelievably hard, and I felt like giving up constantly. I hoped that maybe, even though I knew I put down carpeting again, I could buy a nice rug and throw it over the rotten patches and just try not to think about them any more. I knew how bad this would be, and I knew that now that I could never have peace of mind until I fixed the floor. But the anxiety was unbearable and the panic attacks even worse.

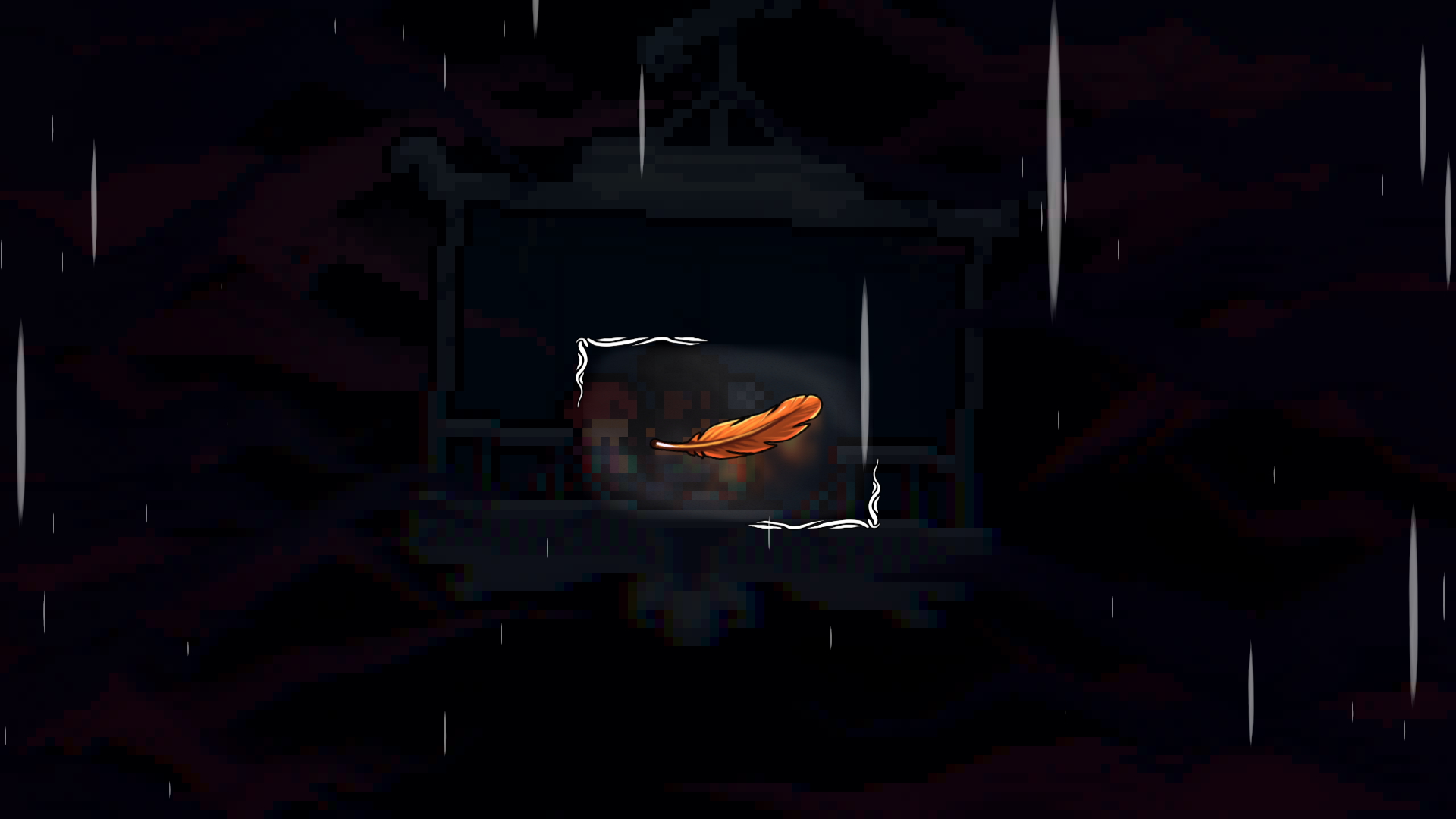

It was right before the worst stretch of that worst week that I played through the end of Celeste’s fourth chapter. The first of the chapters that actually involves climbing a mountain, it’s unusually story-light until the very end, when the gondola Madeline and her friend Theo are taking across a chasm stalls out in midair. The screen darkens, tendrils snake in from every side, and you see Madeline’s sprite heaving up and down far too quickly. She’s having a panic attack. Her friend calmly explains a trick his grandfather taught him for coming down: imagine a feather floating in front of you that you have to keep in the air by breathing deeply and delicately. As he says this, a feather appears in the center of the screen, although the tendrils continue to writhe and Madeline continues to hyperventilate.

I stared at the feather for maybe half a minute, waiting for the game to go on, before realizing that this wasn’t a cutscene. It was part of the game. When I pressed the jump button on my controller, wind picked up to pull the feather toward the top of the screen. When I released it, the feather softly tumbled down. One of my friends would later tell me she’d found herself breathing along with the feather to keep it afloat, and I did too, involuntarily and then knowingly, because it felt right. It’s touch-and-go for a bit, but as you breathe with the game, the tendrils start to recede, Madeline’s gulps of air get steadier, and the screen slowly fades to black.

Another reason trans women don’t talk often about how common it is to feel the pain of repersonalization is because there’s not really an easy answer. There’s not even something simple you can say to a friend to ease their pain.

It’s not like coping with pre-transition dysphoria itself, where you can suggest to your friends that they do a test run of new pronouns with people they trust and where you can hope that they’ll soon be on a linear trajectory toward a happier, more fulfilled life. When a friend of yours is crying in your lap because they just realized they were abused as a child or never processed a loved one’s death or are having trouble accepting that they will never have a childhood or adolescence or young adulthood as themselves, your only options are listening and supporting them and helping them find a therapist if they don’t have one.

These are all good and necessary things to do for people you love, and they are never, ever enough. And if you’re the person sobbing in your friend’s lap, it is crushing to accept that the only way out of this is probably a lot of slow healing work you have to do on your own. Therapy helps a lot, and so do good friends, but neither can fully assuage the inherent loneliness of processing your deepest traumas.

Knowing you are not alone in your pain doesn’t make it go away, but it makes the work easier to comprehend and it makes the lonesomeness ache a little less. It is both depressing and soul-lightening to realize that so many hundreds of thousands of trans people, in that great multitude who came before us and are walking alongside us, are feeling the same sort of pain. It is no longer obscure. It is no longer something you can’t put into words. You don’t have to pretend any more that transition has solved everything, the way so many of us try to so we don’t scare off eggs who are looking for any excuse to keep the carpeting in place.

You might begin to realize that there is life on the other side. When you are friends with or read stories about people who have had to deal with painful revelations amid repersonalization, you have permission to imagine yourself as them. You have a framework. You can be someone who is going to cry a lot and feel hurt and scared and resentful and alone and yet someone who in a year or two will have a much richer life for having addressed the pain. You can be a mountain climber, falling and stumbling as you slowly learn how to ascend the long trail to the summit.

Just breathe.

I finished Celeste a few weeks ago. The story’s emotional climax comes a chapter before the summit itself: Madeline finally stops fighting against the angry, wounded part of herself and starts listening to her pain without judgment. She and her shadow self reintegrate, and they ascend the final stretch together. I was struck by how the game never suggests that this has solved Madeline’s issues with panic attacks or resurfacing trauma. Her journey is not to total healing — that will take far longer than climbing a mountain. No, her journey is to a place where she can listen to her own woundedness, allowing herself space to be angry and despairing and despondent, without giving up on herself.

A few days after finishing the game, I had another panic attack. I’d gone nine days since the last one, which, for me, was serious progress. The trigger was subtle enough that I didn’t expect the reaction I had, but I also might have just been due. I was still at work, and I awkwardly signed off the call I was on before stumbling into the bedroom as the dread slithered in.

I couldn’t stop crying. I felt as though my ribs were contracting and my arms were vibrating, like some alien implant in my spine was shooting electrical pulses to all the wrong nerves. My partner came into the room to sit with me, but I couldn’t be comforted, and I certainly couldn’t be touched or held. I pulled my body into a tiny ball, as if I could vanish. My thoughts ran in a self-loathing loop. I felt like I was about to die.

My partner asked if she could touch me. I said yes, gently. She put a hand on my shoulder and said, “Think about the feather.”

I did. I imagined that white feather, swaying side to side and twirling along its long axis as it floated toward the ground. I took a few deep breaths to keep it in the air, and after a few more moments where I briefly lost control, I managed to keep it aloft until the dread started to recede back into the walls.

I cried for a while after, ashamed I’d fallen back when I thought I’d made progress. I took some more deep breaths and held myself against my partner. The fear and self-loathing quieted. The bed was soft and gentle, and I was deeply loved, and it took some time to remember that a panic attack is not a moral failing, but I got there.

I took a few more moments to let things settle, and then I got out of bed and started climbing again.

Episodes is published three times per week. Mondays feature my thoughts on assorted topics. Wednesdays offer pop culture thoughts from freelance writers. Fridays are TV recaps written by myself. The Wednesday and Friday editions are only available to subscribers. Suggest topics for future installments via email or on Twitter. Read more of my work at Vox.