The surprisingly similar arc of sitcoms about aliens

Why do most sitcoms about aliens start out as hits, then get canceled after season four?

I have a bad habit of viewing everything in terms of patterns and cycles — if something happened once, I keep looking for ways that same pattern repeated itself throughout history. Usually, I’m grasping at straws, because my brain likes to see things that way. But sometimes, I’m really, really not — like with the surprisingly similar histories of sitcoms about aliens.

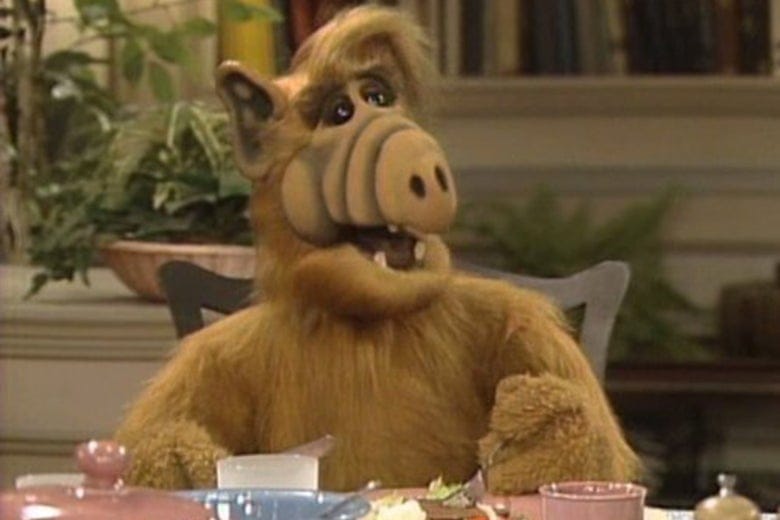

There have been four sitcoms about aliens that could have been credibly called “hits” throughout American TV history. In the 1960s, My Favorite Martian rose as high as 10th in the Nielsens. In the 1970s, Mork & Mindy rose all the way to third. In the 1980s, ALF hit 10th as well, and in the 1990s, 3rd Rock from the Sun spent a couple of seasons in the Nielsen top 30, at a time when TV viewership was beginning to splinter. (Remember when the show distributed 3D glasses for a dream sequence in its second season finale via Barq’s root beer and Little Caesar’s Pizza? The ‘90s!)

Naturally, there have been plenty of alien sitcoms we wouldn’t call hits — foremost among them probably CBS’s short-lived Bronson Pinchot vehicle Meego and the actually-pretty-good ABC show The Neighbors — but all four of the above shows were successful enough to flirt with the American pop culture mainstream. 3rd Rock even became a minor Emmy magnet, which always struck me as unjustified, but when have the Emmys ever made sense?

Look beyond the Nielsens, and you’ll see even more strange overlaps. All of these shows but 3rd Rock inspired Saturday morning cartoons (and I’d wager if 3rd Rock had debuted just a few years earlier when Saturday morning cartoons were still a thing, they would have at least thought about it). Most became big-time merchandising hits, particularly with kids. They all stuck around for several years in syndication, despite only 3rd Rock getting very far past 100 episodes. And most of them featured major stars who would go on from their series to bigger and better things — Martian had Ray Walston, Mork had Robin Williams, and 3rd Rock had Joseph Gordon Leavitt (to say nothing of John Lithgow and Jane Curtin who went into the series as stars). (ALF, of course, won a Tony Award for his searing performance in the 2004 revival of Sondheim’s Assassins.)

But what’s most interesting to me is the strikingly similar pattern all four of these shows experienced. They debuted with a full head of steam in season one — that’s when Martian and Mork hit their ratings peaks. They declined a bit in season two (only ALF went up). And they began to crater in season three, before completely falling off the map in season four. Martian was canceled after season three, while 3rd Rock eked out two more seasons past its disastrously rated fourth (largely because NBC kept hoping it would become a bigger hit than it was). But that all four of them followed almost this exact pattern — hit to disaster in four seasons or less — suggests there must be some vaguely similar way we perceive these shows.

The most obvious culprit is time slot shenanigans. Mork & Mindy famously collapsed from third place to 27th place in its second season because ABC incorrectly thought it was strong enough to anchor its own night. (Clearly it wasn’t.) And when 3rd Rock was canceled, Lithgow bemoaned the show’s 19 different time slots across its run. But outside of Mork, these shows’ networks largely let them be in the time slots where they worked until the ratings abruptly fell apart. ALF largely spent its run on Mondays at 8 pm, for instance, before NBC moved it to Saturdays as a last-ditch effort to revive its ratings. (That effort failed.)

So it goes beyond switching time slots. The answer, I think, lies in how fundamentally flimsy the premise of “alien being arrives on Earth and dissects our quirky ways” is. It seems like it should have plenty of gas in it, right? If anything is clear about humanity, it’s that we sure do have our quirky ways. And there are enough of them that a particularly astute alien observer might find ways to poke holes in all of the silly things we do.

But this isn’t really a premise for a sitcom so much as it is a premise for a series of comedic sketches. You can build a movie around a series of those sketches — most “fish out of water” films follow that basic idea — but you can’t exactly build an entire TV series, where you need a new story every episode. Thus, you have to spend more and more time with the non-alien characters, but the show was sold on the back of the idea “there’s an alien!” Once the alien ceases to be alien, the show functionally doesn’t have a premise.

What’s more, this will happen very, very quickly. One of the things I like banging the drum about is how TV normalizes absolutely everything. Spend a long enough time watching Walter White break bad, and he might start to seem like a hero to a lot of the show’s fans, no matter how much the series’ creators long to tell you he’s not. Spend a long enough time in Gilead from The Handmaid’s Tale, and its ritualistic, state-sanctioned rape can start to seem a little routine.

Dramas have a semi-solution to this problem. They can just keep upping the stakes. Breaking Bad gave Walter nastier and nastier villains to face off with, and it led him to commit graver and graver sins in response. Handmaid’s has shown us places in Gilead that are even worse than the Boston area (with, admittedly, uneven results), and it’s offered an increased focus on the resistance to the Gilead government as a respite from its horrors (again, with uneven results).

But sitcoms — particularly multi-camera sitcoms — can’t really raise their stakes. You can end a season of ALF with the threat of the government taking Gordon Shumway away forever (as the series actually ended), but if the show had been renewed for a fifth season, ALF surely would have been back at home with his human family within the space of a special one-hour season premiere. Sitcoms are typically relationship-based. Mork and Mindy are roommates, and maybe they could date. But where do you go with that eventually? Do you get them married and give them a kid? Sure. But then you’re just another family sitcom — even if the kid is played by comedy legend Jonathan Winters. (I’m not making this up. This really happened in the last season of Mork & Mindy.)

Yes, there are ways to make a sitcom that have nothing to do with core relationships, but those shows tend to burn fast and bright. Indeed, four seasons might be the maximum amount of time you can make such a premise-heavy comedy work — see also: The Good Place and Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt. But even those shows had core relationships that grew and changed, despite the high-concept premises at their center, because those shows all starred real human beings. Once you have a character who exists solely to say, “These humans and their foibles!” you paint yourself into a corner where building real human relationships is impossible because it betrays the core idea of the show.

This is not to say this problem is insoluble — I think The Neighbors worked better because it spent time making the human characters more than just people to roll their eyes at the alien antics. But it is probably such a big problem to solve that it can’t be fixed within the confines of the “built to run forever” network sitcom. The next alien sitcom to be a hit (and there will be one) will almost certainly be on streaming, and it will almost certainly run three seasons of 10 episodes each, because the streaming model is built for shorter runs, and everybody will be sad when it’s canceled, assuming there were many seasons of laughs to come, when in any other time, it would have been right at the point where everything would have started to fall apart.

What I’ve been up to: Hey, everyone! Did you miss me? I’ve taken several weeks off from this newsletter’s Monday edition, after what happened to me in early July. I’m trying to ease back into it, but forgive me if I take a few weeks here and there. I’m still struggling to write quite a bit.

In the time I was away from this, I’ve published a number of things at Vox, and I’m proudest of this profile of actress Eve Lindley, this take on shipwreck YouTube, this look at Taylor Swift’s similarities to Bruce Springsteen, and this paean to The Office and its place in our popular culture.

Somehow, The Office has only grown in stature since it left the air in 2013, bolstered by Netflix, where the extremely limited data there is suggests that it’s a massive smash. Twitter imploded when NBCUniversal announced it would be pulling The Office from the service in 2021.

There are Office crafts on Etsy. There’s Office merch on Amazon and in Hot Topic. Pop star Billie Eilish — a teenager! — samples the show in a song on her Grammy-winning 2019 album When We All Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go? In the midst of the global quarantine due to Covid-19, the show’s stars reunited not once but twice for goofy YouTube talk shows hosted by John Krasinski, who played Jim. The show also lives on as part of the internet’s lingua franca, as anybody who’s ever had to say “NOOOOOOOOO” in GIF form can tell you.

But why? Most shows that become this big in reruns have at least a hint of escapism to them — think Friends (with its candy-colored New York City full of attractive, presumably rich, white people) or The Simpsons (set in an animated world). The Office is a little gray and drab, a little like being devoured whole by a week of Mondays. It takes place in a world where you wear a tie to work, drive every day to a dull office park, where the closest thing to excitement is playing a prank on a coworker. The series features a kind of social realism largely missing from more current notions about the importance of “meaningful” work.

Read me: TV critics have spent a lot of this summer grappling with the legacy of the cop show, but this piece by Alan Sepinwall might be the single best example of the form. It goes in depth and includes a touch of the personal to arrive at the conclusion that big things about the genre have to change.

Since video footage of George Floyd’s killing by members of the Minneapolis PD went viral, there’s been a very public reckoning not only with American policing, but with fictionalized depictions of American policing. The deaths of Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Rayshard Brooks, and the many clips that followed of police officers assaulting peaceful protesters, have gone a long way toward undoing the conditioning of decades of televised stories of heroic cops. That it took a string of horrifying and ubiquitously filmed incidents to turn public sentiment is a testament to how thoroughly television had burnished the image of law enforcement officers as unassailable do-gooders.

Cowboys dominated TV in the Fifties and early Sixties. Many of them just happened to have tin stars affixed to their chests, the better to provide some legal framework for when they slapped leather and gunned down that week’s bad guy. Westerns were eventually put out to pasture, but the idea of lawmen cleaning up their communities by any means necessary remained pervasive. Other professions have fallen in and out of fictional fashion — spies were big for a while, then private detectives, then doctors — but cops are so enduring that characters from other genres often get squeezed into police procedurals when no one can think of a better idea for livening things up. (Not long ago, the Fox network simultaneously had Ichabod Crane, Frankenstein’s monster, and Lucifer helping out local law enforcement in different series.)

From Marshal Matt Dillon (Gunsmoke) to Marshal Raylan Givens (Justified), Sgt. Joe Friday (Dragnet) to Detective Vic Mackey (The Shield), television’s endless flood of cops has accomplished two things. Early on, it presented police officers as infallible heroes who are professionally and temperamentally equipped to handle any delicate situation. Then eventually, it began depicting less admirable cop behavior, but in ways that tended to explain it — and, after a while, to normalize it. These fictional stories have rewired many of us to assume cops are always acting in good faith, and to ignore or wave away those moments when they’re clearly not.

Listen to me: By the time you read this on Monday morning, the first half of the second season of Arden, the scripted audio fiction podcast I co-created, will be available on your podcatcher of choice. I’m ridiculously proud of this season, and if you have never listened to the show and want a place where you can hop in, consider the third episode of this season (Spotify, Apple Podcasts), which introduces our main case for the year and features some absolutely phenomenal work from our cast (which includes people you might know from the TV like Zach Grenier and Rebecca Metz). We have moved heaven and Earth to get this half-season out in the midst of Covid-19, and I’d love if you checked it out.

And another thing… This tribute album to Adam Schlesinger, one of the brains behind Fountains of Wayne, as well as so much great movie and TV music (particularly from the series Crazy Ex-Girlfriend), is really terrific. Schlesinger died in March from Covid-19, and his loss will make the music world all the poorer.

This week’s reading music: “Calling Occupants of Interplanetary Craft” by The Carpenters

Episodes is published once per week and is about whatever I feel like that particular week. Suggest topics for future installments via email or on Twitter. Read more of my work at Vox