The repersonalization of Emily VanDerWerff

On discovering you exist

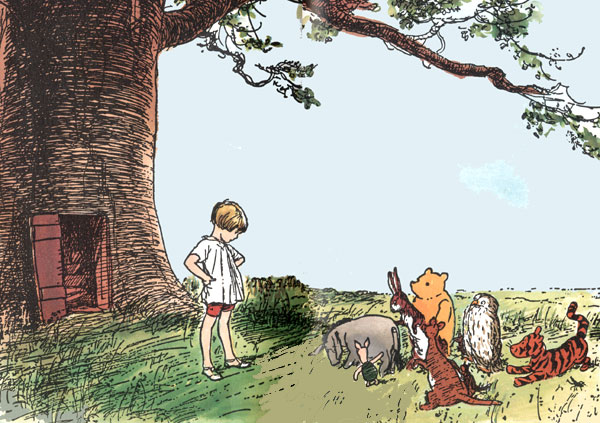

One of the stories that has followed me my entire life involves a 3-year-old version of myself. When asked what my name was for my of that third year, I would apparently respond “Christopher Robin” with such confidence that many people around the little town I grew up in became convinced my name was Christopher.

This story has always been told by my parents with a chuckle and a nod toward my future life as a writer. I loved Winnie the Pooh so much that I decided I was the story’s main human character via some sort of 3-year-old logic. I did this a lot as a little kid. I took my favorite stories and tried to force my way into them, as though my core being was a plug-and-play application just looking for the right hosting software. That’s why this story has always been told with an eye toward my fascination with narrative that would become my life’s work. Look, the logic goes, the kid loved stories so much that she tried to become one.

And there’s something to this. I was fascinated by stories as early as I can remember. I kept trying to understand why they held me in such thrall and almost immediately began figuring out ways to decode them. When I later met my biological father’s family, I discovered that one of my uncles was a born storyteller as well and had tried to turn his experiences in the Vietnam War into a memoir before his death. Some part of me was always going to have one eye turned toward the world of the make believe.

But I’ve been looking back on my days as Christopher Robin with a more jaundiced eye since admitting to myself that another fictional character I always tried to embody was Laura Ingalls Wilder. (My fondness for playing Little House on the Prairie at recess and insisting I get to be Laura is not something that comes up nearly as often in my family’s narrative of me as my flirtation with being Christopher Robin. I wonder why…….) I didn’t actually think I was Christopher Robin. I knew on some level I was pretending. But I also knew that on some level I was a fiction.

There’s an idea in trans circles that’s called “depersonalization.” It’s especially popular with binary trans people in their narratives of themselves, though it can, of course, apply to anyone who feels cast adrift from the gender they were assigned at birth. The basic idea of depersonalization is that as the trans person approaches and then reaches puberty, the things that make a human being a human being start to shatter and come apart.

Let’s make this metaphor even more explicit. In early 2017, I visited Amsterdam, where a church named the Oude Kerk (literally “old church”) sits in the city center. It has stood for almost a millennium and is now largely a collection of art installations designed to encourage your most pretentious Instagram tendencies. One of the installations when I was there consisted of shattered mirrors thrown on the ground so that they were in great shards of glass, reflecting the ceiling and stained glass windows in splintered fashion.

You could see yourself in these mirrors, but from an odd angle, and carved up into pieces. Beyond you was some other world that you, standing on the ground, could not reach. And because the light in the church mostly came from above, the mirrors had the odd effect of making you a silhouette, blocked out by strong light from behind. You were not really a person. You were a cipher. The real world was through the mirror.

This is how I felt all the time when I thought about myself — I was a collection of pieces, reflected. I was not a whole. I could see that somewhere behind me was a whole other world of light and color, but I could not reach that world no matter how hard I tried. I was a dark blotch on the landscape, a smudge that would maybe be filled in later with a person.

I felt this way as long as I can remember, even before I was aware I was maybe trans, was probably trans, was definitely trans. I felt like a story in the process of being told, something probably not helped by the fact that I literally didn’t know my origins (being a child of adoption) and belonged to a faith that insisted I was a part of God’s plan. All around me were signs that the world was whirling toward something., if only I could stand still long enough to be brought back around to see it.

The real trick of explaining the trans identity to anyone is that it’s impossible to understand until you’ve taken the leap to admit that, yes, you are trans. If you are cis, ask yourself, what does it mean to feel like a person? I will wager that you’re not sure how to answer this without resorting to some half-baked answer from philosophy, psychology, or religion (that’s fine). (If you read that and thought, “Well, nobody really feels like a person,” maybe look in to that.)

When I first came out to a (cis woman) friend of mine, she told me about a moment when she was very young and was out and about with her parents, when she was seized with the sudden happy thought that she was a girl, and she liked being a girl, and she couldn’t imagine being anything else. I didn’t have that moment, but most people don’t. But I went one step further than that, even. Not only did I not have that moment, but I kept expecting to just turn in to somebody else.

Early in our relationship, I told my wife to her horror that I wanted to have every experience, to visit every place, to try every thing. This is probably some stark difference between my extroversion and her introversion on some level. But I added on another thing that she reminded me of just the other night: I said I wanted to be everyone.

I was 18 when I said this, so I of course knew I wasn’t going to suddenly morph into another human being. But my parents remember when I was a kid and would ask them when I might finally become someone else. I couldn’t have told you who “someone” was — maybe a little boy who lived with his best stuffed animal friends in a hundred acre wood — but even then I had a deep and abiding sense of wrongness that I tried to solve via story. I was a character in a fiction. A writer was figuring it all out.

Sometimes when I read back over things I wrote as a child or a teenager, it’s embarrassing the degree to which this theme kept cropping up, my fascination with the idea that somebody somewhere was designing the story I was a part of, which robbed me of any agency and trapped me in its grip. Because I was always most fascinated by television, I usually interpreted my life through the lens of being a character in a TV show. I had no choice but to break up with my girlfriend, because the storyline was getting boring. That time I became depressed and suicidal in my junior year of high school was a ratings stunt. When my marriage almost fell apart, my efforts to hold it together were desperate and raw and real, but some part of me was calculating just how amazing the story was playing for the audience.

I was always aware of how, on some level, this was a pathology that didn’t help me. But by the time I was in high school, I was filling whole notebooks not with journals but with episode guides, trying to find the pattern in the noise of my own life. If there really were an infinite number of universes, I reasoned, then there were an infinite number of universes in which I really was a television character, and the events of my life really were some other batch of humans’ entertainment. (By this same logic, every TV show we watch here is a dim reflection of some “real” universe somewhere, an idea I find oddly comforting, which probably shows you exactly the brand of fundamentalist Christianity I grew up in.)

I didn’t tell people about this, because I knew it was a crutch that would be badly misunderstood. And to a degree, it did help me start to develop my own theories about storytelling that have helped me succeed in my various chosen careers, as well as push me to make several dramatic choices that improved my life. I quit a job that I hated because I reasoned the people who were watching me didn’t want to see me so frustrated and beaten down. I reached out to The A.V. Club because I wanted my story to be a little more exciting. I began gender transition because—

That last one is a trick. Every time the part of my brain that said, “Hey, this would make a great story!” butted up against the part of me that knew the real story of my life was the whole thing where I was a woman despite all appearances to the contrary, I would rationalize my resistance to that inherently compelling story arc. Trans representation on television was all well and good for people in my universe, but in the one where I was a TV show? Forget about it.

This is why I’ve become convinced my oldest and deepest coping mechanism for dealing with my own depersonalization, the shattered mirror on the floor of my brain, was the notion that I was a fiction. Indeed, the instant I came out as trans, the coping strategy’s hold on me immediately began to wane. I no longer need it. I just don’t think that way any more. I found a way into the mirror, and I no longer want to be somebody else. I want to be Emily.

Good luck telling that to all of the people counting on Christopher Robin.

Christopher Robin is actually a potent metaphor for transness. The real Christopher Milne resented his father for the way in which Christopher’s childhood was robbed from him and turned into a commodity. For as long as he lived, Christopher Milne could not escape Christopher Robin and the flights of fancy he had as a child. My own childhood was not turned into a commodity, and I was shoved down into a box regardless. It was robbed from me in a very different way.

So I opted in. Somehow, my 3-year-old brain deciphered that if the options were “become a fictional character” or “lose everything to a world that will never understand” the former was preferable. I embraced my own unreality until I had wrung it dry. And after the last few drops were squeezed out, I had to try something else. What else did I eve have?

I was always dimly aware that if my ultimate goal was to become a television writer (which it still nominally is), then turning my own life into a television show was a lousy way to go about doing so. For one thing, nobody really wants to see a realistically presented drama about a TV writer. For another thing, I kept taking stuff that should have been a good fictional plot twist and endlessly ruminating on what it might be like if it happened within the fictional world of my show, which is to say within our very real reality.

(I want to be careful here to point out that I understood that the world itself was real and the things I did within it mattered to other people and to whatever eternal and divine presence is at the universe’s center. I did not, thank goodness, fashion myself as an antihero drama, and now I wonder what the people watching me thought of a show that was centered so much on a character who was always about to do something.)

I kept myself back from my “real” life because I thought my real life was in the waiting for something else to happen. The second I came out and especially the second I started taking estrogen, I realized that, no, life wasn’t going to just happen to me. I was going to have to find a way to make it happen, regardless of whether people in another universe who didn’t even exist found it entertaining.

I’ve been thinking a lot about this repersonalization, the part where I fell through the mirror, the part where I suddenly realized that I existed. It is a little like a religious experience. It is also a little like suddenly realizing you have vast oceans of time in your past that you filled only with darkness, seeking out a lighthouse that had its beams turned inland instead. (Hey, another metaphor!) Make it to shore, maybe, and you stood a chance of finding warmth. But good luck getting there.

Every time I feel like I have a firm grasp on who and what I am now, I suddenly am confronted with a whole new layer of the self that needs to be attended to. I recently turned 39, an age fraught with terror in our youth-obsessed world, but my brain is still arrested somewhere in early adolescence, and my emotions are trapped around the time when I decided I wasn’t the boy my parents said I was but, rather, a fictional one who lived in my favorite book series. (If you gotta be a boy, choose the very best!) I am 39 and 29 and 19 and 9 and 3 simultaneously, and to be alive in that space is to feel a little unstuck in time.

The act of transition is about pulling those shards together, just as the act of coming out is finding your way through the darkness to the shore. But the glass is sharp, and it cuts your fingers. There are so many things buried inside myself that I am only just now coming to terms with. But I know one thing. I know I am Emily VanDerWerff, a real person and not a fiction, who is doing things because she wants to do them and needs to do them and can’t believe she gets this life in which to do them. i lived behind myself in the mirror for far too long, and now I can see what it looks like to stare at yourself dead on. It’s not always pretty, but it’s a start.

Read me: I really shouldn’t use this space to link to my own work, but when I became aware that nearly the last review I was going to write before coming out in the pages of Vox was a review of Fleabag, season two, I used it to ruminate on all of the above. Perhaps it will help you make sense of whatever I’m trying to say even more! (The actual last review I wrote before coming out? Appropriately enough, it was for the Deadwood movie.)

I don’t like to talk about this because saying, “I think I’m a fictional character,” is a pretty good way to make people around you feel very concerned about your well-being. But this little suspicion sneaking around the edges of my consciousness has always been a minor disassociation, a way of distracting myself from myself and inventing reasons that the pain and struggle associated with anybody’s life are part of some larger story that somebody somewhere is telling about me, to the cheers of an adoring audience.

The more I’ve talked to friends about it, or noticed the ways that they, too, mug for unseen cameras, the more I’ve realized that maybe not everybody thinks about reality in quite the way I often have, but almost all of us are aware of it somehow. Modern life feels so weird and meaningless and cruel at times — and modern technology makes it so easy to apply a performative filter to it, in the form of one screen or another — that starting to imagine some other reality just behind that fourth wall over there is tempting, at least a little bit. It’s a detachment. A defense mechanism.

So when BBC and Amazon’s Fleabag — a show about a woman named Fleabag, who is, like me, in her 30s, and who keeps breaking the fourth wall to talk to the audience, sometimes while she’s in the middle of a conversation with somebody on her plane of reality — released a second season that directly addressed this same tendency within Fleabag herself, I almost couldn’t look right at it. It was too bright.

Watch me: Like… I just want to make this space “WATCH WATCHMEN!!!!” every week, because I haven’t been as locked in on a TV show as I am on that one in quite some time. But probably you would like some other recommendation, right? In that case, why not check out one of my favorite underseen Christmas specials, which I wrote about at The A.V. Club some years ago. A Very Merry Cricket is Chuck Jones attempting to return to the Christmas-y ground he trod so well in How the Grinch Stole Christmas. He almost succeeds. Check out a lovely excerpt, then go watch the whole thing.

And another thing… Given all of the above, it’s kind of remarkable I’m not more of a gamer, given my love for investing pieces of myself in complete and utter fictions. And yet I’m just not. Still, this time of year is my favorite for pretending I might yet become a gamer because it’s when Rock Paper Shotgun publishes their advent calendar of the year’s 24 best games for PC. I always see a million things I want to try, then promptly forget to try them because I’m too busy playing Stardew Valley.

This week’s reading music: “You Learn” by Alanis Morissette (and, yo, the version from the new Jagged Little Pill musical kinda rules????)

Episodes is published once per week and is about whatever I feel like that particular week. Suggest topics for future installments via email or on Twitter. Read more of my work at Vox