The Community reviews

Or: How do you escape your past? (You don't.)

For most of my career, the quote that has been most passed around from something I’ve written has been this quote from a sloppy review of a season three episode of Community:

There’s nothing wrong with being happy. There’s nothing wrong with enjoying something so much that it strips away all that irony and cynicism. And there’s nothing wrong with loving anything so much that it feels like it could pull your heart out of your chest and toss it on the floor. We build ourselves up to not do that, and then we build up the armor so thickly that we have trouble finding what’s underneath. We use that as an excuse to lash out at people who do feel stuff, who do like things (and I am, of course, mostly saying this about myself). It’s hard sometimes to remember that the world isn’t a place to glide through, so nothing can touch you. It’s a place to be experienced.

The quote itself isn’t bad, but the review it’s in is a total mess, jetting off in about 15 different directions before sort of getting to some kind of point. Yet this quote stood out for many readers because this was the last episode of the show to air before it went off the air for several months, which seemed to many like a prelude to its cancellation. “There’s nothing wrong with enjoying something so much…” came to stand in for a lot of people’s feelings for the show itself. It’s the one quote of mine that has been excerpted on Goodreads, which is pretty weird, all things considered.

For many years, I had a grin-and-bear-it sort of relationship with this quote. I didn’t have any clue when I wrote it that it would become so beloved. In fact, I don’t remember writing that quote at all. The other quote of mine that has taken on a life of its own — the paragraph that begins “What I believed for too long, and what you might believe too, is that your body is not a gift but an obligation” in “The Catastrophist” — hit me like a lightning bolt one day, and I had to find a place to write it down before I lost it. But “there’s nothing wrong with being happy”? Lost to the brain fog.

I remember writing that review. I remember liking the episode but having no idea how much I liked it, because I found my own emotions difficult to articulate. I remember feeling obligated to like it, which is never a great place for a critic to be in, but I was “the Community guy,” after all. I remember the day I wrote it, I didn’t leave my bed. I remember badly wanting to be somebody else but not knowing how to say that. That quote above is not about Community; it’s about gender dysphoria. But I just realized that a few days ago when it swam up into my vision again.

It’s back because Community is on Netflix now, and seemingly everybody who loved the show in the past is watching it again, as are a few new fans as well. (The show has long been on Hulu, and it’s still there for the time being. But for whatever reason, a show doesn’t seem to exist unless it’s on Netflix, despite Hulu’s strong subscriber base here in the States. This has always irritated me for some reason.) Thus, my Twitter mentions have become a parade of people telling me how much they loved my reviews, or how essential they consider them, or etc.

I am trying to tread carefully here, because I don’t want to make it sound like I hate that people enjoy reading my writing, or that pieces I have written have taken on lives of their own. This is what every writer wants to have happen to their work, and I’m so glad anything I have ever written has had as long of an afterlife as the Community reviews.

But I’m also a little irritated by the attention they still get within my career. I thought at first that this might stem from my A.V. Club work in general, but I’m never as frustrated by attention paid to the pieces I wrote about, say, The Sopranos or Mad Men or Freaks and Geeks. I published a book of X-Files reviews, and the hardcover is under my previous name, and I still feel a lot of love for those pieces. (I don’t really love my Deadwood reviews, but that’s a clear case where I think I could do a lot better if I wrote them now.)

One interesting aspect of the Community phenomenon has been that a lot of times when I meet another trans woman, she’ll tell me how much those reviews meant to her at the time, or how they helped her come out, or something similar. It’s always wild to me, because somehow, my writing helped her figure out what she was up to, while only further pushing me into the dark. And the more I try to unravel this particular part of the conundrum, the more I realize that relationship to my own sad past is part of what’s going on.

Because here’s the thing: I had a codependent relationship with Community. It might sound weird to say this about a TV show, but for three or four years there, it was the reason people read me, and it was the show that not only built my reputation but also helped keep the lights on at the publication where I worked. There was an open secret around the A.V. Club offices that every Friday, we watched as the traffic skyrocketed because of the weekly Community piece, and when the show would go off the air for any amount of time, we would jokingly fret that we were going to go out of business. We weren’t, but the degree to which people wanted to read about this one specific TV show on our website was staggering. And I was the person writing about the show.

I do not know if this would have happened to anybody covering the show for us. Initially, I wasn’t supposed to cover the series. I thought the pilot was fine but no great shakes, and I was eager to hand it off to a junior writer. But Keith Phipps sensed that the show was going to be a bigger deal than I thought it would, and he asked me to take on the assignment. I did, and it made my career. But I think there’s a world where any one of the high-profile AV Club writers could have covered that show for the site and done just as well, if not better.

At the time, though, I concluded that I was the reason people were reading, and I had to make sure they kept coming back. This was easy enough during the first season, when I was just having a fun time watching the show and didn’t yet think it was so seismically perfect that it was the future of television. (If memory serves, I slightly preferred the first season of Modern Family.) It was in the second season — a daring season of television I still would put up there with some of the best I’ve ever watched (though it’s more hit and miss than you remember) — that my relationship with the show started to lose the critical detachment it should have had.

For one thing, I became aware the people who worked on the show were reading what I wrote, sometimes very closely. (The first indication of this I had was when I hosted the show’s 2010 Comic-Con panel and heard this firsthand from several people who worked on the show.) That spooked me, because I didn’t know how to be truly honest if someone who made the show I loved might be reading my more critical words. For another, the second season was when the series went from one of several well-performing shows for us to the show that buoyed our traffic every Friday morning and brought legions of commenters to the site. (Some of them are still commenting to this day!)

Again, this was mostly all well and good in the second season, because I really did enjoy that season for the most part. But when the third season arrived, a handful of things happened. The first was that writing about the show was no longer a fun thing I did once a week but so central to my job that I felt, each and every week, an intense pressure to outdo myself from the week before. The second was that the mostly cordial professional relationship I’d had with creator/showrunner Dan Harmon to that point completely ruptured for reasons I’ve never understood, to the degree that he occasionally would subtweet me in interviews, where he talked about critics who read too much into the show. The third was that, out of nowhere, an entire blog started up that mostly existed to dunk on my Community reviews (a blog that Harmon approvingly tweeted out at one point). The fourth was that for as much as I still enjoyed the show (and I enjoyed it a lot), I liked season three significantly less than either of the first two seasons. But my brand was such that I felt like I couldn’t say that. (Notably, within The A.V. Club world, season three was when several of our most well-known writers kind of turned on the show.) Thus, my reviews became weirdly stiff and performative, full of effusive praise I didn’t entirely mean and bogged down by my own attempts to alleviate the pressure I felt to be the world’s number one Community fan.

Season three was also when my reviews were at their most popular. Whatever I was doing was working. Whatever I was doing was at least partially a lie.

I’ve been rereading some of those pieces today, and they’re almost all a complete mess. I needed an editor badly, who would help me sharpen my ideas. But they’re also bad in a way that can never entirely be alleviated, because I was going out of my way to not admit to myself that what had been fun now felt a little wheezy and hard to maintain. (And when I say that, I don’t know if I mean the show or my reviews.) They’re centerless. They’re avoiding something obvious that they don’t want to think about. Which brings me back to gender dysphoria (of course).

Inevitably, the thing that people who respond to my Community reviews respond to in them is my central idea that the show is about sadness. But I had a weird habit of saying every show was about sadness in those days (see also: Glee), perhaps because I was desperately, desperately sad and unable to coax myself out of bed some days. I knew, deep down, what I had to do to live the life I was meant to lead. (There’s a reason those reviews write so often about what a great character Britta is.) I could not, in any way, bring myself to live that life. So I channeled that into writing about a television show, in a way that spoke to a lot of people and made them feel seen, some of them so much that they found the courage to come out. It would take me several more years to get there.

(Total sidebar: I also completely hated giving episodes grades, something that was common for A.V. Club writers, because it was never clear whether we were grading a show against itself, against all of television, or both. It was sort of all of the above, but officially, we were grading the show against itself. Except if we actually did that, C grades would have been far more common, and fans would have gone apeshit. So we kind of just gave grades within an extremely narrow range that made B+’s seem like failing grades. It was a fucked up system.)

Harmon was fired from the show at the end of the third season, and once season four rolled around, the series wasn’t as popular with our readership. I continued to cover it, but other shows took over as our biggest series, like Breaking Bad and Mad Men and the then-ascendant Game of Thrones. Community became just another part of my job, but whatever overwhelming love I’d had for it at one time had mostly become buried. Even when Harmon returned for the fifth season, I felt detached from the series. Ironically, the thing that made it come back was the final season, which I didn’t have to regularly cover (being at Vox at the time) and which I ended up wildly enjoying, more than almost anybody I know.

Yet Community is still the reason I have a career that has afforded me all sorts of weird luxuries. It’s ground zero for everything that followed, and for a lot of readers, it’s still the primary thing they think of when they think of my work. To be clear: I don’t want to tell anybody not to love those reviews. There’s some strong writing in there (and a very obvious total lack of editing), and I’m glad that writing made people feel more seen.

But when I read over those pieces, they feel like they were written by somebody else. There is something in them that is trying too hard, that is performing a kind of knowing, world-weary masculinity. My best friend, a fellow trans woman, talks a lot about how when she was living as a man, she latched on to the kind of masculinity seen in the film High Fidelity, an all-knowing, catalog-like knowledge of pop culture meant to stand in for a personality. Loving a show like Community, with its voluminous series of references to other pop culture, was like a shorthand for being that sort of dude — good and well-meaning and extremely obsessive about minutiae.

What’s fascinating about this is that this version of masculinity often really is compensating for some other thing. In my case, it was my hope I would never have to look seriously at the small voice screaming at me that I was really a woman, but it could have just as easily been depression or a lack of meaningful relationships or all-encompassing grief. We don’t teach men to feel things in America, not well at least, and the nice thing about being a High Fidelity pop culture man is that you can offload those emotions onto that pop culture. If you can point at an episode of television and say, “I feel like that,” well, then you don’t actually have to feel like that.

Maybe that is what I find most difficult about being so heavily remembered the Community reviews, then. I have changed, in ways both obvious and not so obvious. I have grown. I have become a better person, more articulate about my feelings and more capable of expressing those feelings. I’ve also become a better writer, because I have several more years of doing it under my belt (along with an emotional clarity that has come from coming out). And I have written so much stuff over the years that I think better expresses the person I’ve become and the person I actually am.

But the reviews are still the reviews. There’s nothing wrong with them, not really. I’m glad people love them. But every time I read them, I remember the too-warm apartment I wrote them in, the stickiness of the bed I rarely left, the slow-motion sense that I was throwing my life away. But I had this one thing, this one thing people knew me for, and in that world, I was quite well known indeed. I loved a TV show, and then I merely liked it, but I felt like I had to love it. And eventually, I had to leave it behind, just a little bit, in order to find my way back to myself.

After all, in the end, there’s nothing wrong with being happy.

What I’ve been up to: It was a really strange week for me at Vox. I recommended TV shows to watch while you’re distracted, felt disappointed by the Netflix movie The Half of It, and found myself both impressed by the Parks and Recreation reunion and hoping nobody got any ideas from seeing it.

It also seems to have taken inspiration from a somewhat unlikely source: the recent duo of Saturday Night Live episodes produced with the cast sequestered at home. In and of itself, this isn’t remarkable. SNL is the highest-profile program to have produced any new episodes since quarantine began, and Schur is an SNL veteran himself. But what’s interesting is the way the special seems to have taken structural cues from the sketch comedy.

If you look at the special as an episode of a sitcom, it mostly falls flat. The story, such as it is, barely exists, and its big moment of emotional catharsis involves all of the characters performing a song from the show’s best season, in an ending the special doesn’t remotely earn. But if you think of the special as a collection of comedic sketches starring the Parks and Rec characters, it hangs together much better.

Read me: This newsletter by my friend Katelyn Burns about how often cis people talk about trans people like we’re not here, listening to everything they say about us, is straight fire emoji.

Predictably, backlash emerged to the backlash to the paper.. Many media members who depend on stoking trans controversies were quick to seize on the retraction, painting it as activists erasing the work of “good” scientists.

It is important to notice who has been missing from this conversation. This is cis people talking to other cis people, about trans people, as if we are animals displayed in the zoo.

Gliske himself penned a brief post on Medium in response to the retraction of his paper. Among a few criticisms he addressed was one in which reviewers claimed it was “disrespectful” or “ludicrous” that he suggested “the experience of incongruence between one’s body and desired gender could be due to changes in an individual’s sense of gender, rather than an individual having the brain sex of the desired gender.” But his response to this criticism is particularly enlightening…

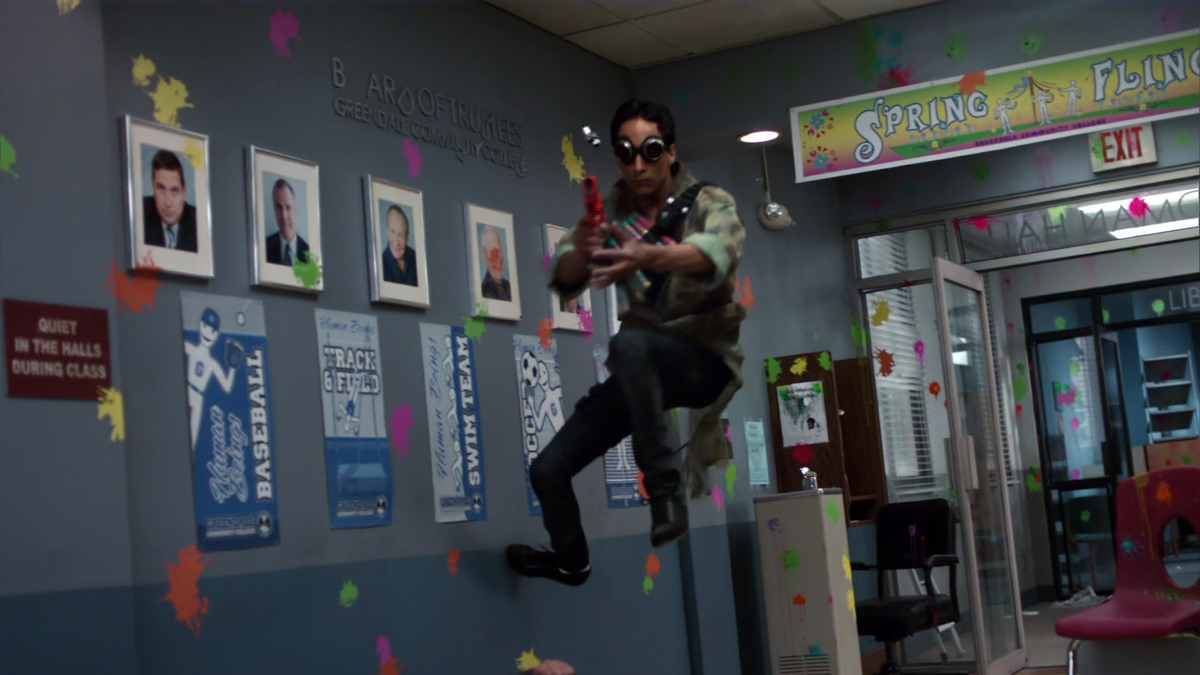

Watch me: You guys heard of this show Community? It’s pretty good, and it’s on Netflix now. I hear there are some solid reviews of it, if you know where to look.

And another thing… My friend Cassie LaBelle is doing an ongoing Twitter thread of reviews of every single fast food chain, and I find it delightful, even if she’s wrong about most of them.

This week’s reading music: “Wedding in Finastere” by Jens Lekman

Episodes is published at least once per week and is about whatever I feel like that particular week. Suggest topics for future installments via email or on Twitter. Read more of my work at Vox