The best advice I've ever gotten for writing fiction

Why and when to think about your story from a new perspective

Over the weekend, I tweeted a lot about WandaVision. I had mostly enjoyed the show but found the finale so disappointing that I don’t know that I will revisit the series. I’ll be writing more about the show for Vox, but in the midst of a tweet thread, I said something that seemed to strike a lot of people as advice they’d never heard before:

Having trouble viewing this tweet? Click here to open original tweet.

(Text of tweet, for those unable to see it: “‘What does this story look like if it’s told from the perspective of the character with the fewest lines?’ is SO IMPORTANT in serialized fiction, and both Mando and WandaVision struggle with that in unique ways.”)

The context of what I was saying stemmed from the ways in which the series’ final episode seemed aware that its protagonist had done something truly terrible, but also, somehow, not aware enough of that fact. (I also lumped in The Mandalorian, which had a disappointing second season finale whose failures mostly stemmed from its inability to escape its connections with the Star Wars universe at large, a similar but much more easily fixable problem.) WandaVision somehow found itself in an uncanny valley where it left a bad taste in many mouths for a bunch of different reasons. For many of us, it was callous about the pain of several supporting characters; for many others, the finale’s storytelling awkwardly lurched between the action they craved and the plot resolution they didn’t really care about.

The problem, as I see it, is that the show’s writers and producers seem to have struggled to see the story of the series from the point-of-view of anyone who isn’t its protagonist. Thus, the series is aware that the other characters are mad and have good reason to be mad, but it isn’t really aware of the depths of that anger.

When I talk about things like this, people assume that what I want is for a show to stop dead in its tracks and give a long monologue to the barista about how the events of the show seem to them. But that’s not really true. I’m not talking about what audiences see on screen so much as I’m talking about what work the writers put in even before the thing shoots. If I’m writing a scene in a coffeeshop, I probably don’t need to know everything about the barista’s life, but it would be good to know how they feel about their job that day, how they feel about the way the protagonist treated them while ordering, etc. The best way to make a story’s world feel fleshed out is to make the people within it feel fleshed out.

This idea stems from some great advice I once got from a big-name showrunner, who was at that time working on their most popular show. I asked them just why the world of the show felt so alive, and they said more or less what I mentioned above: In each and every episode, they thought a bit about how the world of the show looked to the people who had the least lines. That way, if the show wanted to suddenly do a full scene with an extreme supporting character, that character’s perspective wouldn’t come as a surprise, even if the audience was seeing it for the first time, even if that perspective was an unexpected one.

Once you have a vague idea of how a tertiary character feels about the world of the story, you have a better idea of the scope of your world, and that work will show, even if you’re, say, writing a novel in close first-person, where you never leave the protagonist’s point-of-view. The random people the protagonist meets every day are going to feel a certain way about the protagonist, and even if the protagonist is oblivious to this, the reader won’t be. It makes for a richer, more detailed experience, and I often feel as though I can tell when a writer has put in this work.

Now, you can become overrun by analysis when you do this. Like I said, you don’t need to know what the barista ate for breakfast that morning. If the barista is only in that scene, then their opinion on the story is necessarily a small window, and probably a very limited one: What did the protagonist order, and how did they treat me when they did? You could work up a reason for the barista to, say, be a little snippy or whatever, and that might be fun. But it might also become distracting.

Thus, the trick of doing this is balancing the necessary work of thinking about the world through perspectives other than your main character’s versus the needs of the story and plot itself (where the odds that you’ll need to know everything about the barista’s day are very small). My general rule of thumb is that the shorter the narrative, the less you need to think about this, and the shorter the screentime, the less you really need to work at it. A one-scene character in a movie requires less thought than a one-scene character in a novel requires less thought than a one-scene character in a TV show, because the longer a story runs, the more the verisimilitude of its world becomes important. But it’s highly unlikely any of these characters would require endless amounts of consideration.

Another key thing to note is that no matter how much work you do considering the points-of-view of every character, those characters can’t read each other’s minds in the way you can. Dana Hamill in season two of Arden is a character who basically doesn’t care about anyone but herself. (She maybe cares about Olivia.) Knowing how deeply Rosalind cared about Dana didn’t change knowing how callously Dana could treat Rosalind. It just helped us twist the knife a little more.

To bring this back to WandaVision, I don’t really know that the writers of that show needed to spend any more time thinking about how Wanda felt about what she had done. What was necessary was spending more time thinking about how everyone else felt about what she had done. It was there that I found the show’s storytelling seriously lacking, as though its reality extended only to the perspective of its protagonist, a dangerous zone for a serialized story to be in.

What I’ve found is that the more I’ve done this, the more it’s become an automatic reflex. I don’t spend a ton of time thinking about the world of the show from minor characters’ point-of-view anymore because I have a writing muscle that is already doing this. Heck, we had a whole episode in Arden season two retelling the story of the season from the point-of-view of supporting characters, and we wrote it in a week, simply because of the character work we had already put in. (Then again, Arden is a show almost entirely about point-of-view, and our writers room tends to talk about this concept more than most writers rooms do, I imagine.)

Do you need to do this? Not really. I don’t think any writing advice applies unilaterally, because writers are very different. (The one exception might be writers of nonfiction, who should at least try to get inside the heads of their sources, if only to find biases that might not be immediately evident.) All I can tell you is that applying this principle has made my writing feel richer to me and has helped me more readily develop characters and worlds that feel more real on some intangible level. I’d love to hear if this process works for you, too.

Talk back at me: Are you a writer? Comment with the best writing advice you’ve ever gotten! If you’re not a writer, give us advice for your field of expertise. (Comments are only open to paid subscribers!)

What I’ve been up to: I wrote a bit about WandaVision at Vox, in advance of the finale. The article attempted to synthesize a bunch of the online debates over the series, though it necessarily didn’t touch on all of them. Then, of course, the finale invalidated a lot of those arguments by creating several new ones, but that’s the biz.

With the arrival of Covid-19 and attendant quarantines, the MCU went silent. Its planned 2020 releases — movies Black Widow (originally scheduled for May 2020) and Eternals (originally scheduled for November 2020) and TV series The Falcon and the Winter Soldier (originally scheduled for August 2020) — were all pushed to 2021. These shifts have allowed for a seriously crowded 2021 for Marvel, which is currently scheduled to release four movies and six TV shows this year. A full year off from Marvel discourse created a vacuum that the first Marvel project to return was bound to fill with a vengeance.

Enter Disney+ series WandaVision, the unassuming sitcom pastiche/superhero tale/fantastical story about witches (and a semi-serious examination of grief and trauma) that has been at the center of pop culture discourse almost from the moment it premiered on January 15. Originally scheduled for the spring, the series’ early completion made it the first new Marvel project to premiere since Spider-man: Far from Home came out in July 2019.

Read me: I have been enjoying Aaron Reed’s newsletter 50 Years of Text Games, charting the evolution of interactive fiction, both digital and analog. His most recent entry is on Choose Your Own Adventure books, which were, needless to say, a favorite of mine as a child. But the whole newsletter is worth a read.

Bantam’s marketing director Barbara Marcus took on the challenge of selling the unusual book. “A children’s paperback series [didn’t] have dollars, display space, or reviews” in those days, Marcus later recalled. Standard practice was to basically use kid titles as filler, dumping them on bookshops along with more profitable adult books and letting the stores figure out what to do with them. When asked how she promoted the new series, Marcus remembered: “We did absolutely nothing except give the books away. We gave thousands of the books to our salesmen and told them to give five to each bookseller and tell him to give them to the first five kids into his shop.” The decision to print the books in standard paperback size rather than an oversized children’s format was also a shrewd one: younger readers felt like they were reading a real, grown-up book, and early teens didn’t have to feel self-conscious about being seen with one. The numbering, too, was a clever idea, suggesting there were other titles you were missing out on and encouraging kids to trade books or fill in the gaps in their collections. The series soon became a massive success.

While the format would seem to offer little room for experimentation, some books pushed tentatively against its boundaries. In Inside UFO 54-40 (CYOA #12), the winning ending—finding a legendary anti-authoritarian utopia—exists only on a page you were never instructed to turn to. Trouble on Planet Earth (CYOA #29), unlike most books in the series, changes the reality of the fiction with each choice you make: it’s less a book about exploring alternate choices than entire alternate universes. Hyperspace (CYOA #21) featured all manner of time-and-space-bending threads, including a CYOA book-within-a-book and the author, Ed Packard, showing up within his own story. A key to the books’ popularity was that, unlike with the parser-driven computer games of the time, it wasn’t possible to input a failed command. To navigate the story, all you needed to know how to do was read. Computer games would eventually make a similar turn, sacrificing simulationism for more fool-proof methods of input, but not until the Windows model had supplanted the command-line interfaces of earlier machines.

Watch me: I think I’ve written about the YouTube channel Be Kind, Rewind in this newsletter before, but the latest video on the legacy of Faye Dunaway’s performance in Mommie Dearest pulls together everything the channel has been talking about for years now. It’s a terrific piece.

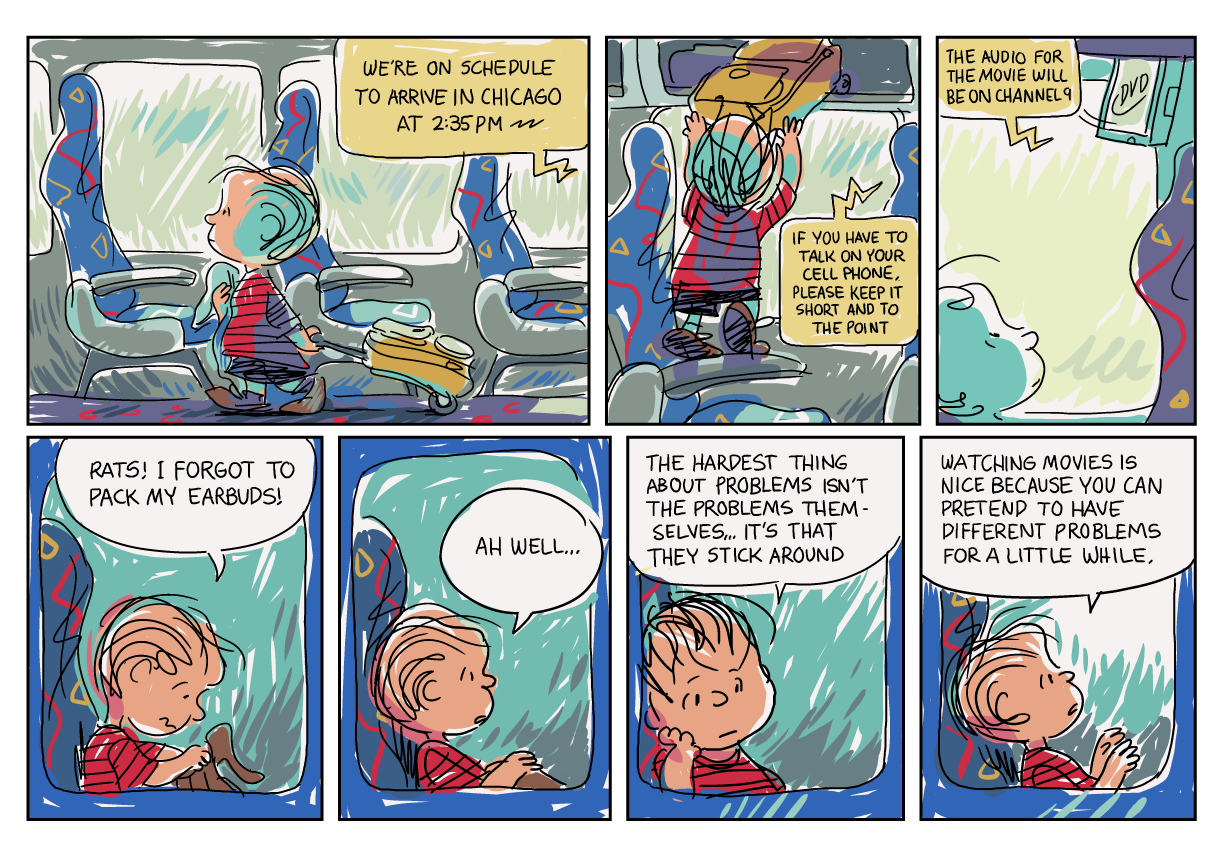

And another thing… As a trans person and a Peanuts fan, this take on Linus and Charlie Brown, all grown up, is a moving meditation on what we lose as we age. I loved it!!!

The first small portion of Good Ol’ Charlie B. (Credit: Marina Kittaka)

A thing I had to look up: I keep forgetting whether to capitalize the V in WandaVision (you do, indeed, capitalize the V).

This week’s reading music: “Thru and Thru” by The Rolling Stones

Episodes is published three times per week. Mondays feature my thoughts on assorted topics. Wednesdays offer pop culture thoughts from freelance writers. Fridays are TV recaps written by myself. The Wednesday and Friday editions are only available to subscribers. Suggest topics for future installments via email or on Twitter. Read more of my work at Vox.