Class and the modern romance novel

Romance as a genre can't escape the long shadow of that hot rich guy Mr. Darcy. Should it?

To one degree or another, all modern romance stories owe something to Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice. In the same way that Frankenstein serves as ground zero for our modern science fiction, Pride and Prejudice has proved so durable a romance plot that novelists are still reworking it to great effect to this very day. (Obligatory link to my favorite romance novel, a queer retelling of P&P.)

The core of Pride and Prejudice is what might be called an "enemies to lovers" plot with a soupçon of "grumpy/sunshine" added in to boot. (If you are my college English literature professor, please stop shuddering at my description of your favorite novel using modern romance novel tropes.) Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy dance around each other, verbally sparring, wearing down each other's defenses, until, defeated, Darcy can only admit his love for Elizabeth. Hooray for love!

In truth, of course, Pride and Prejudice is about a great deal more than its romance plot, especially when said plot is considered within the context of the era in which it was written. The book features heavy elements of social satire and commentary on early 19th-century marriage customs, with a great deal of irritation at the notion that a woman is only as good as her marrying prospects. The novel's famous first sentence – "It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife" – reduces the woman in the equation not just to an object but to the object of a prepositional phrase.

(Jane Austen sidebar! Austen places "wife" at the very end of the novel's opening sentence to make sure it sticks in your mind most readily, but the structure of the sentence itself reduces the importance of "wife" as much as it possibly can relative to the other words in the sentence. As an object of a preposition, the word has little room to maneuver. To rework the sentence into one where "wife" is the subject results in something borderline nonsensical. This prison is the one Elizabeth Bennet is entangled in as the novel begins, and the first sentence places you in it with her. But enough about how Jane Austen is great! This is a newsletter about other things!)

Regardless of how you feel about Pride and Prejudice as a novel of manners, you also have to admit it's a brilliant romance story. Elizabeth and Darcy are such good foils, and in a world where romcoms are absolutely full of their progeny, it's all but impossible not to read what we know of modern romance back onto the book. So many folks have gleefully riffed on this book over the years that when many of the reviews of my beloved 2005 film adaptation (the Keira Knightley/Matthew MacFadyen one) bemoaned the film replacing social satire with swooning romanticism, I felt a little annoyed at the idea that one couldn't do a swooningly romantic adaptation of the book. Why not? Right?

The more I think about this, though, the more I wonder if in reducing Elizabeth and Darcy to archetypes that recur throughout one of my favorite genres, we've lost some of Austen's nose-thumbing at the expectations of women of a certain class in her time and at the very idea of marriage as a chance at class-betterment to begin with. Even Austen lost sight of this a bit. Pride and Prejudice, after all, ends with Elizabeth giving in to the matrimonial expectations the book has so thoroughly tweaked. That she's marrying someone she truly loves is a victory, of course, but she's also marrying a guy who's going to make her fabulously rich.

Modern romance as a genre is generally interested in how issues of gender, race, and sexuality intersect with a love story, but it too often seems to look the other way when it comes to class. Many a romance novel or film either focuses on financially comfortable to obscenely rich characters or simply pretends class doesn't exist.

Please note that I did not say "all." There are certainly romances that feature working-class characters, struggling to get by. But they tend to skew more toward romantic drama (Nicholas Sparks, of all people, plays with these ideas from time to time) and away from anything lighter. Some historical romances play with these class distinctions, with the idea of whether the wealthy person and/or member of the royalty can ever marry a commoner, but that presentation of class is often more like that seen in a fairy tale.

I do not know that there is anything wrong with this. I don't particularly read romance novels for gritty realism (most of the time), but it does seem like almost every romance book I read now underscores that at least one of the two potential lovers is financially set for life, if not both of them.

It even extends to stories set in what we might think of as a working-class milieu. Tessa Bailey's It Happened One Summer, for instance, features a charming romance between a seemingly vapid Hollywood socialite and a gruff fishing boat captain. When it comes time for the two to talk money even tangentially, Bailey makes sure the reader knows the fisherman is loaded because he owns his own boat and takes in the lion's share of the profits. To some degree, this flips a stereotype on its ear. A fisherman who owns his own boat probably could be a millionaire, rather than a working-class stiff just trying to keep ahead of his landlord. However, I found myself rolling my eyes at the need to underline the guy's level of wealth.

In a similar vein, Christina Lauren's The Soulmate Equation features a solidly middle-class single mom who has a love-hate thing with a techie dude that eventually becomes true love, as you'd expect. The book (and its companion, The True Love Experiment) can't simply have the mom end up with a guy who's got enough money for them to live comfortably. It has to have him sell his dating app for so much money that they and their kid will never have to worry about money ever again. They have joined the American ultra-rich, and all is well.

(Sidebar: "Guy who designs a mega-successful dating app" is quickly becoming a new trope in romance novels. Unsurprising? I guess?)

Central to a lot of romance is the fantasy of being swept off your feet, and in a world where the gulf between the rich and everybody else grows wider every day, it's a lot easier to imagine being swept along by love if the person you fall for is rich enough to never have to worry about money again. And romance's love of someone who's rich and powerful being undone by a protagonist coded as relatively "normal," again, stretches all the way back to Mr. Darcy. So it's not like these stories don't come by their ultra-rich love interests honestly.

Yet even in books where the issue of class is mostly set off to the side in favor of other elements, it's simply assumed the characters always have enough money to do whatever they want. Even in my beloved Written in the Stars, where the two lovers are an astrologer and a wannabe actuary (God, what a pair), they're both just successful enough – or come from successful enough families – that they don't end up having to think about money very much at all.

Naturally, there are plenty of literary genres where a focus on class isn't particularly necessary, and it's possible romance is one of them. So why do I get so hung up on it here and not in, say, space opera? I think my annoyance stems from how closely romance has to track the inner emotional state of a character, and in many of these novels, the characters' inner emotional states are rarely roiled by wondering how they're going to pay for an unexpected car repair or something. My wife and I generally have enough money to afford the things we need, but we're always a couple of disasters away from being flat broke. So it rankles because if you were writing a romance novel about me, I would be thinking about my bank account a lot. Then again, if I were doing that, maybe I wouldn't have the mental space to fall in love.

Maybe I just need to make my peace with the frequency of this trope in romance. Maybe if everybody in every romance novel I read was staying just ahead of the poverty line, the books would cease to be escapist fantasies (probably they would). Maybe I need to stop looking for every genre to be able to do everything and just accept that there are certain things certain genres are better suited to.

Yet I still find myself thinking about this a little more with every new romance novel I read (and I read a lot of them). In a time when we're more aware of income inequality than ever, it really feels like the "Thank God I found a hot millionaire to marry" trope should come with an added side of increased self-reflection. Then again, having the character think about these issues, then run off with the millionaire anyway (because true love always wins) could end up making them feel like a huge hypocrite. Maybe in a romance novel, as in real life, money can't buy you love but it can sure buy you the security and space to really make a go of it.

Talk back to me: My guess is that a lot of my concerns would be alleviated if I read more self-published or indie romances. So what are your favorite romances that involve folks who have to scrape to get by? Bonus points if they involve single parents because I'm really into that right now for some reason. Tell me in comments or by replying to the email version of this newsletter!

Consider becoming a paid subscriber: Running this newsletter is absurdly expensive, and by becoming a paid subscriber, you'll both help keep the newsletter online and keep posts like this free for those who can't afford to upgrade. But you'll get other stuff, too! Paid subscribers get access to comments, a weekly discussion post on Fridays, and occasional other special posts and features. There will be some other fun treats along the way. Click the button to learn more!

Three things: I am on vacation this week, so these three things are all vaguely beachy, you know? (If you include "going whaling in the 1800s" as "vaguely beachy.") (And you should.)

- It wouldn't do to have a romance-themed newsletter without offering a romance novel recommendation, and I really enjoyed Elle Kennedy's The Summer Girl. My least favorite part of the romance novel formula is the third-act breakup, and Kennedy had one of my favorites in a long time, thanks to some soapy complications she leaned into perfectly. The book's interest in parent-child relationships also gave it a thematic spine that gave the conclusion some real weight. If you're looking for a late-summer beach read, well, this book has summer in the title!

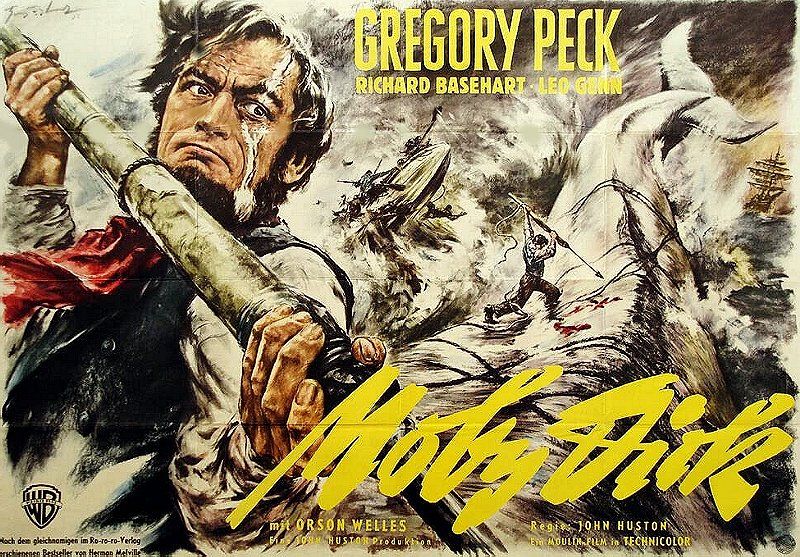

- Do you want to hear me talk about a totally different novel('s film adaptation)? Then consider listening to my appearance on the podcast This Had Oscar Buzz, where I talked about John Huston's 1956 adaptation of Moby Dick, a film for which he received a DGA nomination (which would normally portend Oscar glory), only for both his and the film's Oscar hopes to fall short. Alas!

- Is there a better soundtrack for your beach day than this set of Taylor Swift mega-mashups? Possibly! But if you're me, maybe not!

This week's reading music: You're Working the Night Shift at Kmart on a Stormy Night by TortoiseCity

Next week: How to make lemonade

Episodes is published twice a week, with an edition for all subscribers on Wednesdays and one for paid subscribers on Fridays. It's written by Emily St. James, who covers whatever she feels like writing about, but if you have suggested topics, please reply to the email version of this newsletter or comment (if you are a paid subscriber).