The eerie prescience of Satoshi Kon's Perfect Blue

The 1998 anime film predicted our world of online celebrity and all the terrors that come with it.

(Each week, I’m publishing a new pop culture essay from a freelancer. Remember: Your subscription fee helps me pay these freelancers for their efforts! This week: Nubia Jade Brice on the eerie prescience of Satoshi Kon's Perfect Blue.)

In the 2020s, if you’re not sharing your most intimate thoughts and private details online, do you even exist? Or better yet, does your existence even really matter? If someone can’t check your Twitter right now and see what you’re up to, will people assume you’re not doing anything at all?

Considering how strongly the previous millennium advocated for privacy, this change in attitude likely wouldn’t have been predicted by commentators at the turn of the century. In 20 years we shifted from keeping our online family business in the family, to recording our every move for clout. But in the late ‘90s, Satoshi Kon’s forward-looking anime feature Perfect Blue dared to ask the question most viral wannabes fail to consider: “What’s the worst that could happen?”

Perfect Blue, which was released in Japan in 1998, was incredibly ahead of its time. The anime horror feature tells the story of Mima Kirigoe, a B-list pop star turned actress, who achieves internet fame on a website called “Mima’s Room,” dedicated to broadcasting her every move and thought to her adoring fans. It’s exactly the kind of self-marketing strategy people expect in the 21st century, one that offers an invasive peek that fans swoon over. Yet the movie takes place in the ‘90s, long before the terms “internet celebrity” or “influencer” were coined. Besides, Mima doesn’t own a computer. She doesn’t even know how to work one. So who’s updating her site?

At first, Mima thinks nothing of the site. She even purchases a PC to read the day-to-day accounts of what she is supposedly up to. She is entertained to the point of being unbothered. “They know me so well,” she giggles, without an ounce of fear. The idea of self-preservation that has been instilled in the average internet user today is unfathomable to her. It’s all new. She doesn’t yet know what to be afraid of.

As Mima struggles to rise to fame, her TV roles become more risque, and the entries on her blog become personal to the point of being invasive. (Though the term “blog” wouldn’t be coined for several more years after Perfect Blue’s release, it’s the best description of “Mima’s Room.”) Whoever is writing the blog knows where she is, her deepest fears, her superstitions. They even write what she’s thinking so accurately that any fan would think she wrote the posts herself. It’s not just that this mystery’s stalker is pretending to be her; it’s that their exclusive looks into Mima’s life aren’t entirely wrong. As the site grows more and more invasive, she struggles to maintain her grip on reality while her MA-rated acting career tarnishes her previous good-girl image. And all the while, the pop group she left behind continues to rise to stardom.

Mima struggles with a sudden level of online popularity that many people would welcome with open arms nowadays. In the age of Instagram and Twitter, the idea of privacy is a fleeting luxury that even the most normal of people no longer have. There’s no use in having something that can’t be shared and monetized for financial gain and internet fame, no matter the emotional and psychological cost.

To many influencers, the cost of privacy and dignity is worth the perks that come with internet infamy. The problem with viral fame is that it makes the poster a worldwide commodity. They’re no longer a tangible person, but an internet persona voluntarily subjecting themselves to being ridiculed, adored, and even imprinted on. It’s as if by sharing a snippet with fans, you’ve created a codependent relationship where their entire livelihood is intertwined with milestones of your life. They deserve to know what you’re doing, and it’s your obligation to give them that. The very people you want to love and admire you now feel entitled to you. In a sense, they own you.

For Mima, the sudden loss of privacy breaks her. She can no longer live up to the ideals that her fans have come to expect from her. They expect her to act and conduct herself as an innocent pop star. Her success, as well as her entire identity up until this point, hinges on her living up to a carefully calculated idol persona. Too many of her fans cannot handle the idea of her rebranding herself into something other than what they’re already familiar with. After receiving an anonymous fax labeling her a “traitor,” Mima quickly learns the problem with internet fame is that it allows faceless fans to project themselves onto people they’ve never met and to expect to be vicariously compensated for work they’ve never done.

These sorts of parasocial relationships are not uncommon. For decades, teens have taped band posters to their walls and wasted countless hours reading interviews in magazines. Now one YouTube search will grant fans hours of content on their favorite celebrities. In most cases, it’s just a harmless fascination or attraction that naturally fades over time. Most people are rational enough to understand their one-sided celebrity object of obsession will never reciprocate their feelings. Yet Mima’s fans seem to think that their opinions and desires hold more weight than they realistically do, or even should.

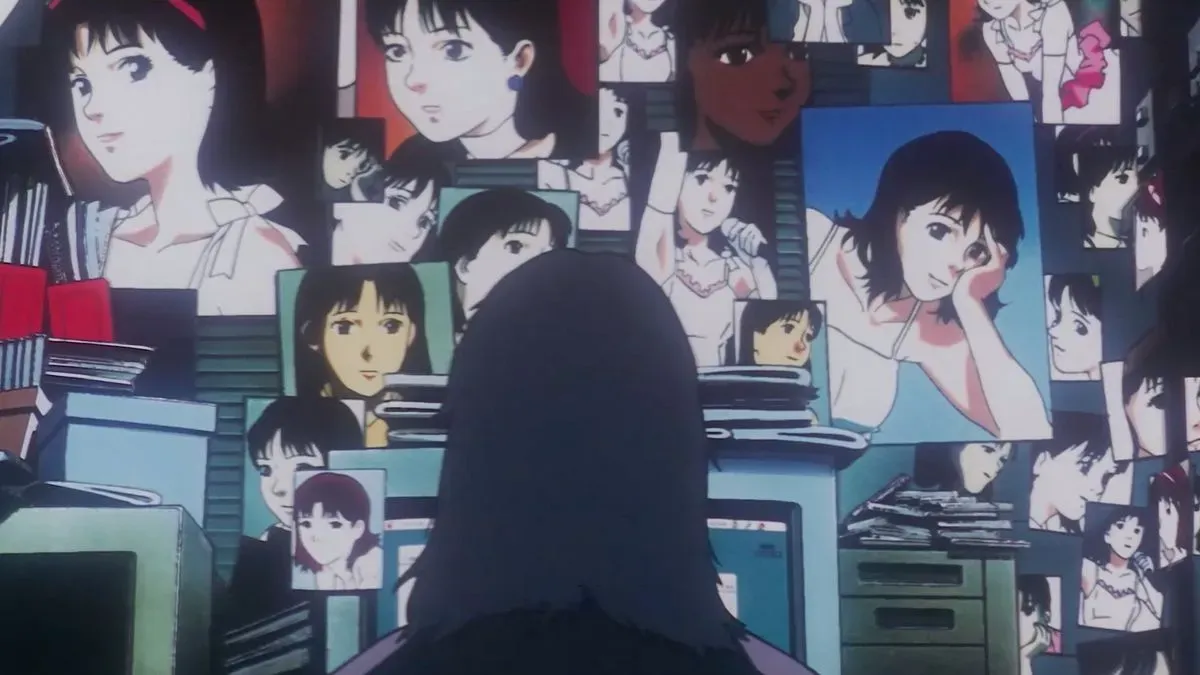

Throughout the film, viewers hear conversations between dedicated fans who feel Mima’s career moves are questionable at best. The audience is also introduced to a stalker fan named Mamoru Uchida, whose all-consuming Mima obsession makes him the most obvious choice for the film’s villain. The more detached from reality Mima becomes, the closer to her he feels, believing that she is reaching out for him to save her from the industry in ways only a truly devoted fan could.

Unfortunately for Mima, attracting a stalker, especially a violent one, is not uncommon in the world of celebrity. Many people are familiar with the stories of John Lennon and Gianni Versace, or more recently, Youtuber Christina Grimmie, all of whom were gunned down by obsessed fans. The internet takes an already faded line in the sand between celebrity and non-celebrity and all but completely erases it until it’s too blurry for even most casual admirers to comprehend fully. Unlike with Lennon and Versace, however, “Mima’s Room” gives Mima’s stalker unlimited access to her private life, further distorting that line, another eerily prescient nod to where online celebrity has gone in the 21st century.

Like many online celebrities trying to make the transition from C-list content creator to certified A-lister, Mima is forced to make questionable career moves that to others may feel like selling out. Often it seems like the drive for fame forces people to consider options they never would have previously, whether that’s creating controversial content for likes, or (in Mima’s case) filming graphic television scenes and partaking in nude photoshoots. Her team knows her 15 minutes will only come at the expense of her dignity, but they manipulate Mima into taking more provocative jobs for the sake of her career. (She’s not particularly into the idea.) Luckily it pays off, and for a moment, all of her sacrifices seem worth it. All it cost her was everything.

Mima’s story, of course, is one of the more extreme tales of the dark side of internet fame. The movie heavily dramatizes her constant misfortune with multiple attacks, including shrapnel-filled fan letters and even a handful of murders aimed at members of Mima’s team. She’s targeted more than once in person, while her character and career choices are under constant scrutiny. It’s no surprise that her mental health begins to crumble as it appears she can’t do anything right for her career or for her adoring fans.

In the final climactic scenes, the culprit behind the vicious attacks and the website “Mima’s Room” is revealed. For someone with so few friends, Mima’s fame puts her on the radar of so many potential perpetrators that it’s hard to eliminate anyone. However, if there’s one thing we’ve learned in recent years from cases like Meghan Markle’s and Brittany Spears, when it comes to fame, it’s often the people closest to you that end up betraying you the most.

Being safe online doesn’t get views or clout or even pay bills. It costs to be an internet sensation, and most times, those costs aren’t the kind that can be quantified in numerical value. Perfect Blue’s Mima Kirigoe never asked to be immortalized in an internet blog, but the internet made it possible for people to find her anyway. Her privacy was taken from her, and that theft was justified under the illusion that everyone wants to be ultra-famous. While many viral hopefuls these days would welcome being discovered under the heat of controversy, Mima just wanted a meaningful career.

Contrary to popular belief, not everyone seeks to broadcast their private lives online for attention, fame or otherwise. But these days anyone can go from no one to trending with nothing more than a cellphone video. All attention is not necessarily good attention. From the moment we create that new blog or post that gently retouched Instagram photo, we never stop to think, “what’s the worst that can happen?” Because to too many, the worst that can happen is to never have been famous at all.

Episodes is published three times per week and edited by Emily VanDerWerff. Mondays feature her thoughts on assorted topics. Wednesdays offer pop culture thoughts from freelance writers. Fridays are TV recaps written by Emily. The Wednesday and Friday editions are only available to subscribers. Suggest topics for future installments via email or on Twitter. Read more of Emily's work at Vox.