How Kenley Players brought Broadway to the masses

Did Midwestern theatrical impresario John Kenley reinvent onstage stunt casting? Honestly, yeah.

(Welcome to the Wednesday newsletter! Each week, I’m publishing a new pop culture essay from a freelancer. Remember: Your subscription fee helps me pay these freelancers for their efforts! This week: Margaret Hall on Midwestern theatre impresario John Kenley, whose love of stunt casting just might have changed Broadway forever.)

In the years before Broadway’s Covid-19 shutdown (which began March 12th 2020 and will hopefully end September 14th 2021), you might encounter a handful of predictable elements when going to see a show. Your seat would not have enough leg room. The curtain would go up at least five minutes later than advertised. And chances are, producers had brought in a TV or film star to bolster the marquee potential of the production.

This habit of star casting in stage shows wasn’t always the case. In the 1940s and '50s, Broadway stars were bonafide celebrities, recognizable figures even to those who had never set foot in a theatre. Entire columns of newspapers were dedicated to chronicling their comings and goings, audiences leapt to their feet when these stars appeared on nationally syndicated game shows, and their names were spoken in the same breath as the top earning film stars. (In fact, many of them became top earning film stars.)

By the mid-20th century however, there was a pronounced cultural shift away from theatre, linked to the rise of rock ‘n roll and a new generation's rejection of what they saw as their "parents entertainment." Grand dames were out, and rock stars were in. In the middle of it all, one person in northwestern Ohio set off a grenade in the hierarchy of theatre, the ripple effects of which could still be felt on March 12th 2020, when a number of celebrities had Broadway runs cut short.

The name of this grenade thrower was John Kenley.

Born to Slovakian saloon keepers in 1906, John was born in Denver Colorado, after the family had fled increasing prohibition laws on the East Coast. Born intersex, John (who occasionally went by "Joan" but utilized male pronouns when at work) entered show business when the family moved to Cleveland Ohio, where he worked as a female impersonator, acrobat, dancer, and audience plant at comedy show before he made the move to New York City. There, he worked for the legendary modern dance choreographer Martha Graham as a dancer and acrobat before working as a play reader and assistant to the Shubert Brothers, theatre owners who founded one of the most powerful organizations in Broadway history. Every actor that came to New York had to go through Kenley, and he steadily built up a little black book of the greatest talents in the industry, calling his network his “Kenley Players.” In 1940, he took that name to Deer Lake, Pennsylvania, a resort town for Appalachian coal barons, where he created the first official Kenley Players theatre in a converted church.

To say that Kenley’s productions quickly became a local religion in Deer Lake would be an understatement. Theatre had been considered by many to be entertainment for “city folk.” National tours as we now know them were scarce at best, and if your town hadn’t existed during the Vaudeville era when the routes were originally drawn up, you were out of luck. Your community theatre likely didn’t exist as far as New York producers were concerned. If you didn’t live near a big city like Chicago or Cleveland, anything beyond a school pageant was in short supply.

Thus, demand for theatrical entertainment was so high that Kenley soon expanded out of his first theatre, creating his own tri-city circuit of summerstock theatres in Columbus, Dayton, and Warren, Ohio. He then expanded into Michigan, with the number of theatres north of Lake Erie depending on the demand that season, creating what was effectively a tristate touring circuit, with productions playing in different theatres in different regions depending on the month.

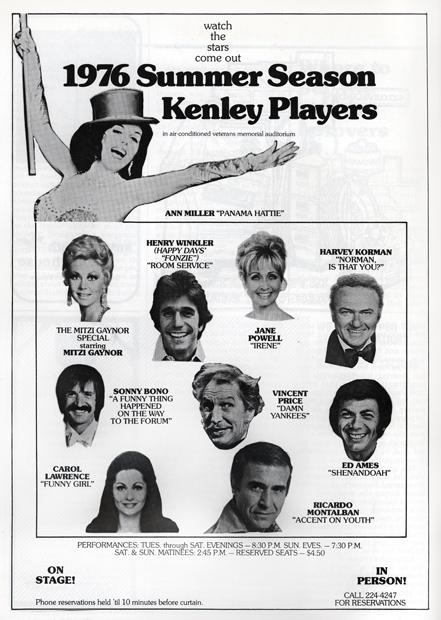

It was on this circuit that Kenley began a practice that would become his signature: stunt casting. As a summerstock theatre, the run of shows at Kenley Players was short, with productions rarely running more than a few months. This restricted length made Kenley productions highly attractive to film and television actors, who could fit a run in between filming schedules.

The actors Kenley had met and networked with in his Shubert days had matured into some of the most famous stars of the era, and he would bend over backwards to showcase them in his productions. He built shows around whoever was available, including several production adjustments of questionable legality. Script adjustments and song interpolations were common, often without permission from copyright holders (He famously ended a 1975 production of She Loves Me with the song “What I Did For Love” from the brand new Broadway hit A Chorus Line; that show’s mastermind, Michael Bennett, sent a telegram in lieu of a cease and desist).

For the hundreds of stars who called Kenley Players home, the arrangement was ideal. In the 1950s, many film and television stars were not taken seriously as artists, with kudos instead extended to theatre performers. The divisions of high- and low-brow entertainment were stratified, and performers struggled to establish “legitimacy” offscreen in order to build up artistic respect. A Kenley Players run was just long enough to establish a theatrical career without putting a film career on pause the way a year-long Broadway contract would. For Broadway stars turned film stars, such as Marlene Dietrich, a Kenley Players run gave them a chance to stretch their theatrical muscles in between high-profile (and high-payout) films.

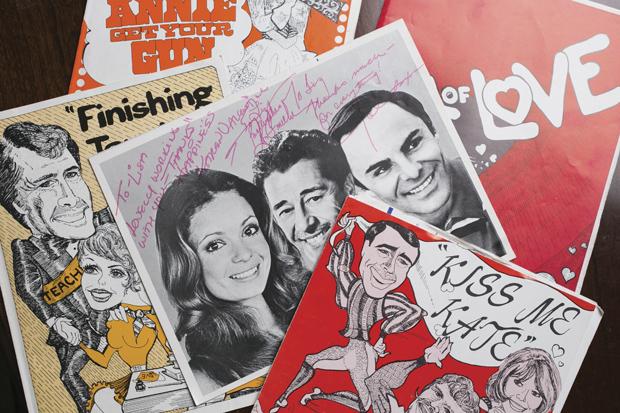

Anna Mae Wong was met by an adoring legion of fans during the very first season, when she performed in the play On The Spot. Robert Goulet and Tommy Tune got their starts on the circuit, and Betty White, Gordon MacRae, and John Raitt were regulars throughout the 1960s. Paul Lynde, perhaps best remembered for his long tenure on Hollywood Squares, worked the touring circuit so often that he became its unofficial mascot, alongside Kenley stalwart Ann Miller.

To call Kenley’s casting choices unorthodox would be an understatement. While some were predictable (Jayne Mansfield performed in Bus Stop after the film starring Marilyn Monroe was released), many were an unusual marriage of performer and part. Nowhere else in the world could you see Billy Crystal as the Emcee in Cabaret, Ginger Rogers as Annie Oakley in Annie Get Your Gun, and a visibly pregnant Barbara Eden as Maria in The Sound of Music. Even Joe Namath, the former New York Jets quarterback, got in on the action for a production of Picnic.

Kenley Players steadily became the most successful summerstock theatre in the country, with the circuit playing to audiences of thousands every night by the 1970s. Kenley was deeply committed to making theatre accessible, with cheap seats often priced at $1.50 so a kid could save up their allowance to see a show every summer, creating a new generation of theatre devotees. Working in and around the circuit became an industry unto itself. Thousands of Ohio teenagers picked up summer jobs as gophers for the circuit, including my own mother. (A gopher is essentially a “go” person, tasked with fetching items for higher up members of the company. My mother, for instance, was usually assigned to the talent that would come on and offstage, as she was good at remembering exactly what kind of pantyhose Mitzi Gaynor needed, amongst other small details.)

Kenley’s domination of the summerstock circuit began to wane in the late 1980s, when his stars began to age out of their performance prime, and new national tour routes began to thin out demand for his productions. 1995 was the last officially recognized season, with Robert Goulet in South Pacific, Barbara Eden in Best Little Whorehouse in Texas, and Tony Randall in The Man Who Came to Dinner, amongst others. John Kenley lived to nearly 104, and passed in 2009. Obituaries mourned him as one of the greatest Midwestern theatre impresarios.

Kenley’s ideas did not die with him. While star casting had been around since the dawn of Broadway, Kenley’s particular brand of bringing film stars to the masses had caught on like wildfire long before his death. In 2009 alone, you could see The West Wing’s Allison Janney in 9 to 5, Full House’s John Stamos in Bye Bye Birdie, and American Idol’s Constantine Maroulis in Rock of Ages. As production costs had ballooned and general public interest in the theatre had waned, many producers looked at John Kenley’s stunt-casting ways as a blueprint for how to bring new blood to the theatre.

By 2020, it was next to impossible to open a Broadway show without some type of Hollywood name attached to it, be it a performer or a brand. A show like the Temptations jukebox musical Ain’t Too Proud could get away with casting all theatre performers, as it had an existing band’s fanbase to rely on, but many shows opted for the safer bet of bringing a flashy star’s fanbase along for the ride. The 1996 revival of Chicago, which has become the longest running American musical in Broadway history, turned the practice into an artform, with celebrity athletes, reality show stars, and pop stars taking turns in the cast, alongside many others. Shortly before the Covid-19 shutdown the show had even run its own digital competition show to cast a fresh face as Roxie Hart. (It is currently unclear if the winner, Emma Pittman, will take on the role once Broadway reopens.)

Whether or not the reliance on stunt-casting will continue is currently up in the air. In the years leading up to the shutdown, many theatre fans grew tired of the promotional move, especially as the power of the Broadway star continued to wane. 2019 hit Hadestown and several other critical darlings found their footing based on artistic merit and not flashy names above the title, and as Broadway reopens, it is those stalwart theatre fans who will be filling seats long before tourism rebounds.

Regardless of how stunt casting is utilized in the future, the impact of the Kenley Players circuit cannot be ignored. John Kenley sent shockwaves throughout the industry due to his blending of the theatre and film worlds, permanently changing both mediums. In many ways, his taste came to define theatre for an entire region, and by extension, an entire generation.

Episodes is published three times per week. Mondays feature my thoughts on assorted topics. Wednesdays offer pop culture thoughts from freelance writers. Fridays are TV recaps written by myself. The Wednesday and Friday editions are only available to subscribers. Suggest topics for future installments via email or on Twitter. Read more of my work at Vox.