How Florence and the Machine convinced me to call myself disabled

On concert parking lots, important doctor's appointments, and the casual ableism of the everyday

(Welcome to the Wednesday newsletter! Each week, I’m publishing a new pop culture essay from a freelancer. Remember: Your subscription fee helps me pay these freelancers for their efforts! This week: Allison Darcy on an unlikely personal revelation spurred by Florence and the Machine.)

In June 2019, there are two important dates on my calendar: a rheumatologist appointment I have waited five months for and a Florence and the Machine concert.

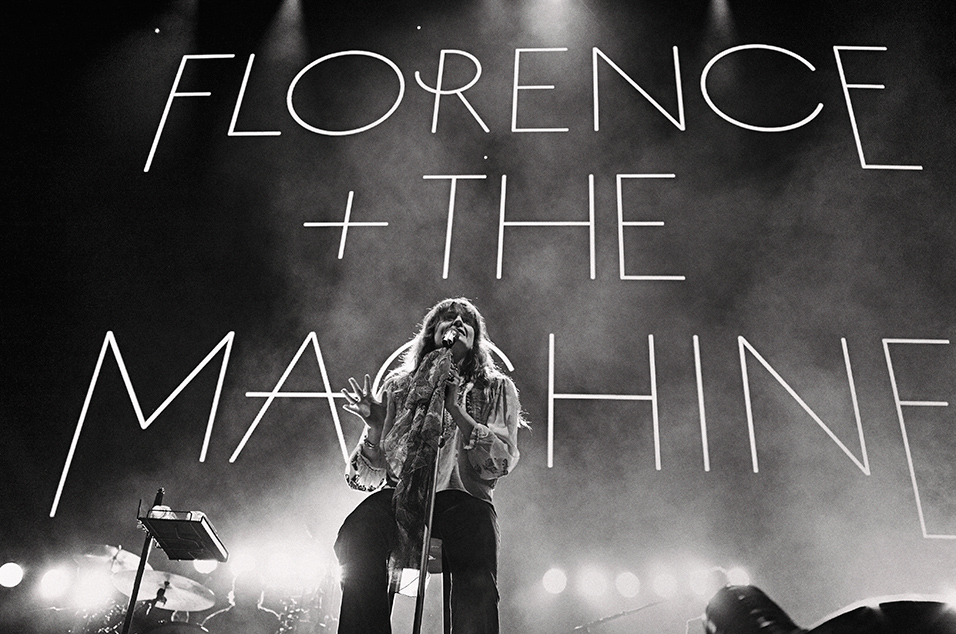

My best friend, Madeline, likes singers like Florence Welch, who twirl and flutter about the stage between their effortless, inimitable vocals. Admittedly, I’m not always on board with her music taste — but when I hear a semi-mainstream musician Madeline has followed for a decade whom we can both sing along to is on tour, taking her to see the group seems like the perfect birthday present.

It is true on the day that I get us the tickets. It isn’t when the day of the concert arrives.

Madeline knows that I have been in pain for six years. Yet I cannot tell her the week leading up to the concert has felt like wading through sandpaper, that my shallow sleep has been disrupted every night. I don’t want to give her the chance to say we don’t have to go.

I don’t want to give her the chance not to.

My rheumatologist appointment would be a routine one, even if tinged with the faint outline of hope. For three years, I had lived in a repetitive cycle: over-Googling what was wrong with me, trusting too much that an expert would figure things out, returning to denying the feeling of my muscles pulling from my joints like old gum, and over-working myself — because apparently, I was normal and supposed to live like a normal person.

Three urgent care doctors, one DO, three primaries, one neurologist, one psychiatrist, and five physical therapists all told me the same thing in the end: “There’s no logical reason you should be in this much pain.” And each time, I’d give up. For a while. And then, I’d get back to hoping someone — anyone — could figure this out and cure me. That’s where I was by the time my June 2019 appointment came.

Anyone diagnosed with a chronic illness or disability as an adult can tell you that the moment of actual diagnosis is not necessarily one of doom and grief, the way movies and able-bodied friends imagine. If anything, the moment often comes with a sense of relief: This pain, these strange symptoms are real. You were right. And though I certainly did feel that when my all-too-brief appointment ended with exactly the diagnosis I thought I would eventually be given and the finality attached to it — no, my pain would not go away; no, there was not a known cause or fix — I surprised myself with crying. A part of me, it turned out, had been holding out through all the Band-Aid fixes and tests. A part I didn’t know existed had still thought this could be simple and curable, that I could somehow be wrong about the diagnosis that all my symptoms fit.

But I wasn’t.

The declaration was made simply, quickly, and without many details. The rheumatologist did not take the time to hear my concerns or fears, and all her recommendations were just platitudes I’d already heard. When I started crying, she spoke to my husband instead of me.

The website of the concert venue where we will see Florence states that anyone who needs to use the accessible parking can. At least, it says that the day of the show. It says a placard is not needed. It is not implied; it is explicit: You do not need a parking placard. I am confident it says this. I checked six times.

I don’t require this parking, if it is limited and the space is needed for someone else to access this concert — but it is preferable when there’s room, and at this pain level, it will be the difference between us getting as close to Florence as we can with our cheap tickets or sitting up at the top of the hill, closest to the lot and farthest from the stage. The ability to use the accessible parking feels like an ice-pack for my ego, whose bruise has gone unnoticed despite all examinations.

I tell Madeline on the way that I am testing out the word “disabled.” She nods. Does not comment. She rolls down the window when we turn in, our car diagonal between lanes. The labeling is unclear. We can’t figure out which to be in.

“Sir,” she asks a parking attendant, “Are ADA and VIP parking the same?”

“No,” he says, “ADA means American Disabilities Act.”

“Yes,” she says, “Okay. Yes. But is this the right lane?”

“This is the VIP lane.”

“Right. Is it also the ADA lane?”

“That’s American Disabilities Act.”

“Which lane,” she sighs, “is that?”

“Oh. I don’t know,” he says. “Ask the first person you see on your left.”

When my wait for my appointment came to an end, I lost my carefully metered optimism, but I didn’t actually fall away from my research habits. Instead, I took to the internet, library, and friends-of-friends trying to define the word “disabled.” I’m unsure I ever hid the fact that I was acting for myself particularly well, though I tried, not wanting to offend anyone. Still, I suppose I knew what I believed from the moment I made the first search.

The way I cook, groom myself, and imagine my future had started to change half a decade ago: a difficult and non-linear process of grieving the latent dreams that I could one day dance on Broadway or that I'd be a confident, bar-hopping party girl well into my 30s. As I began to lose functionality in undergrad, I’d moved from calling myself an extrovert to an introvert, unable to explain in any other way that I actually did need 10 hours of sleep to get through the day. Four days leaving my apartment in a row generally required at least 48 hours recovery time. Could someone who could theoretically function like others, for a short time (just with lots of suffering and to the detriment of any other commitments) call themselves disabled? I knew one thing either way: Able-bodied, I was not.

When I asked the rheumatologist what to do with her prognosis — "go back to PT, practice better sleep hygiene, try to stay positive!” — I knew the most important lifestyle change would be the hardest. I needed to ask for help.

Well, I wasn’t about to start doing that. Not with people I knew, anyway. But there were small reaches I could make. Little bits of change. Ways to move through the world that didn’t make me feel like an inconvenience.

We keep driving in search of the ADA lot. The first person on the left tells us it’s coming up on our right. We drive until there is nowhere left to drive. Nothing comes up on our right. She asks someone else, who says there was a sign “a ways back.” We turn around, and slowly, looking closely, find it: unlit, small, and half peeled off, the sign for accessible parking is almost invisible from the road.

I allow myself to exhale when we pull up to what is essentially a field of rocks with a dozen cars. There is room for maybe 50 more, and we are among the last to arrive. “Is this ADA parking?” Madeline asks. I’m eyeing the gravel.

“Do you have a parking placard,” the woman standing guard says, no question mark present in her voice.

“The website says you don’t need one,” I shout through the open window.

“Ma’am,” she says, “this is parking for people with disabilities. What’s your disability?”

And I reply with no hesitation, my words perfectly clear: “Do you want to see the medications I keep in the car, a list of upcoming doctor’s appointments, or my back brace?”

The woman ushers us in silently, and Madeline almost applauds. But this is not a spontaneous mic-drop. This is an answer I knew I’d have to give, even as we asked which lane to be in, even as I checked the website again, even as I told Madeline how excited I was for things to be this easy. This is an answer I rehearsed all day.

I have been warned against Dr. Google by every professional I’ve seen. I am cautioned by the support groups I’ve joined on Facebook: Do not tell any professionals you have been looking things up about your body. Do not tell them you have discussed these things with others who can relate. Do not tell them you think you have this disorder or that one, and never, ever let them think you think you are the expert on yourself.

Dr. Google and the online groups also say what the rheumatologist doesn’t.

Don’t listen to any asshole who tells you to just do yoga, they tell me. Learn strength, little bits at a time. Buy this stand so you don’t have to hold up your hair-dryer. Use frozen meals; there’s no shame in pre-minced garlic. It’s easier to fall asleep on your back if you use a weighted blanket. It’s okay to not see the silver lining. It’s okay to hate your life. Be angry. Mourn. Be loud.

Take the accommodations available to you.

Demand help.

Madeline brings my cracked Android to where people with a certain coupon code are getting free lawn chairs with drink holders. Free chairs, as long as you can lift them or find someone who can. I’m overwhelmed with joy — these are the things that thrill me. Truly, as I get comfortable in the fold-out with my Diet Coke, strapping on my wrist braces (since it gets colder at night and cold makes my joints feel crunchy), I briefly feel something adjacent to celebratory. I asked for a chair. I chose to sit. I’m doing what I need.

Florence floats onto stage. The other women with long, gauze-y dresses and free-flowing hair — which is to say, all of them — shoot up around us. Madeline does too. I have a brilliant view of the mega-screen, and I am comfortable in my seat, and Florence is beautiful, and so is everyone else.

“Welcome to the matriarchy,” Florence says at one point. “Tonight, we are having a collective experience. Put your phone down, and just — just tell the person next to you that you love them.” I can do that.

“It’s not hard to be Florence-y,” she says at another. “Just put your arms up and sort of wave them about.” I can do that.

“I demand you all get up and start dancing,” she says. “This is not the sort of concert where you can just be here and listen. If you come to a Florence concert, you are not allowed to sit.”

I do not believe that Florence Welch is actively ableist. She simply wasn’t thinking about those words. Four years ago, I wouldn’t have thought anything of that sentence. But I do now. I did on that night.

And I do not believe the parking attendants actively wanted to keep me or anyone else from easier lives, and I do not believe someone I hear in the gym saying no one should want to live without running actively believes in eugenics, and I do not believe that the person who calls a pain essay I recommended a “pity party” is actively self-centered. They’re just not thinking about me or other folks with more visible disabilities. We are an extra detail — sometimes, yes, an inconvenience.

I stood for that one song, jumped, waved my arms about. It felt good to get it out of my system. It felt better to sit again after.

Why shouldn’t I use the word disabled? I wondered then. And I decided during the rest of the concert, amid love and music and dancing: I am disabled. It says what I mean, so I’ll say it. I am not able to do the things people parking elsewhere are. I am not able to be the person Florence says her concert-goers must be. Whether or not I identify this way, I am not able. So I might as well stop being coy about it.

I am disabled. I need accommodations. I will ask for help.

And I am coming to the concert. And I am going to sit.

Episodes is published three times per week and edited by me, Emily VanDerWerff. Mondays feature my thoughts on assorted topics. Wednesdays offer pop culture thoughts from freelance writers. Fridays are TV recaps written by myself. The Wednesday and Friday editions are only available to subscribers. Suggest topics for future installments via email or on Twitter. Read more of my work at Vox.