Fleabag: "Season 2, Episode 3" and "Season 2: Episode 4"

In which Fleabag wouldn't like me much

(This is the fifth installment of my weekly recaps of Fleabag, the Prime Video series that aired two seasons in 2016 and 2019. I love the show, and I wrote these reviews in 2020 when exploring the idea of doing a paid version of the newsletter. As such, they don't have all our regular features, but I hope you enjoy them anyway. These recaps are only available to paid subscribers.)

"Season 2, Episode 3"

This is the episode of Fleabag that makes me think Fleabag wouldn’t like me much.

I mean, I know that’s true. Fleabag doesn’t really like anybody, after all, and even the people she likes are subject to her oft-repeated castigation. She oozes snark and pain in a way that makes clear that she is unwilling to live her life in a way that compromises to social niceties. Even now, in season two, when she’s a little more put together, she can’t resist trying to get Claire’s goat. It’s just who she is, deep down in her DNA.

But the scene between Fleabag and Belinda (Kristin Scott Thomas) at the bar is a scene that makes my stomach a little queasy. The context for this is something Phoebe Waller-Bridge surely didn’t intend, but it’s there nonetheless. The UK has been swamped with a wave of virulent transphobia in recent years, represented by the many, many TERFs who are central to much of its political discourse (especially in its opinion pages), so every time I hear a British woman of a certain age talking about what it means to be a woman, then tying that experience to certain biological parts, I get my hackles up.

And to be clear, Fleabag doesn’t entirely subscribe to Belinda’s point-of-view. This is a show about a complicated character meeting other complicated characters, and the ultimate effect of the scene is to make Fleabag rethink her relationship to Claire – as if she sees in Belinda a sign of something in Claire that needs to be healed. And the stuff Belinda says is true. Women are valued less the more their fertility dries up, and older cis women are too often shunted out of society unless they scream and howl (and therefore turn off certain parts of society even more). There is no indication, in text, that Belinda is a TERF or a gender essentialist (someone who would say, for instance, “all women have vaginas,” to use a very baseline example).

But boy, those words in that accent – it was a warning flag for me when I watched this show back when it debuted, a few weeks before publicly coming out. And seeing the scene so celebrated among cis women TV critics at the time made me feel even more isolated.

I’ve softened on the scene a bit over time, both because my coming out went so much better than I ever dared dream and because the episodes that follow place it in more useful context. But goodness, in rewatching it for this project, it still made me feel a little panicky, like my Twitter mentions were about to fill with people telling me how I would always be a man.

And it’s too bad that it comes in this episode, which is otherwise one of the series’ funniest installments and which features the moment when the Hot Priest first notices that Fleabag is talking to somebody else, one of my favorite moments in a TV show ever, ever, ever, both for how unexpected it is and how much it turns what we think we know about the show on its ear. I love this episode, I do. It just hits something very primal in me at the same time, something I can’t avoid.

But who am I kidding? Fleabag would love me. I’m awesome.

"Season 2, Episode 4"

In every great series, there’s at least one episode where everything comes together, where if I said, “I could quibble,” I would be lying. (I think I can always quibble, but sometimes I just can’t.) So it is with the fourth episode of Fleabag’s second season. This is perfect television, from its opening moments to its glorious final shot.

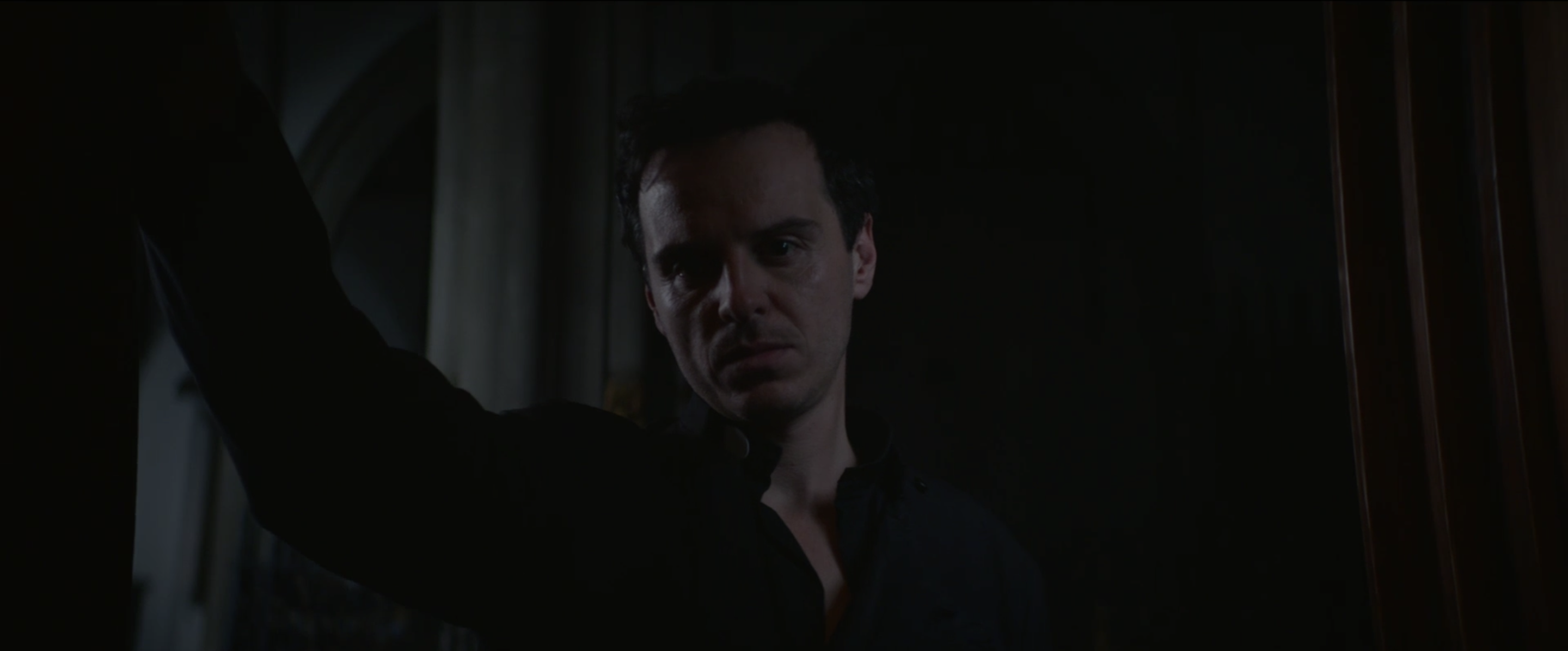

What’s more, it walks the line between the two sides of this show’s personality. It has some tremendously funny stuff involved, but it also turns into one of the rawest, most dramatic moments in the entire run of the show when Fleabag gets into that confessional booth. And then, it’s almost indescribably sexy. The connection between Fleabag and the Hot Priest boils over, and when he commands her to kneel – in a way where you know exactly what’s about to happen – it’s hard to resist the chemistry between Phoebe Waller-Bridge and Andrew Scott.

I almost don’t want to talk about this episode because whatever I might say will feel insufficient. But I want to focus on that scene in the church, from when Fleabag enters the confessional on. Waller-Bridge is not the first person to unpack some level of queer subtext, or at least dom/sub subtext, to the relationship of any random person to the almighty, but she uncovers a rawness within the character that has been carefully hidden all season long. Fleabag has been running and running and running away from her own despair, and here, in an unguarded moment, it comes spilling out.

As I alluded to, there’s a queerness to this that is oddly inescapable. Waller-Bridge, with her tall, thin frame and her coltish gait, has a slightly androgynous feel that meshes well with Scott’s vaguely pansexual energy. It’s alluded to, several times, that something in the Hot Priest’s past caused him to tumble, headlong, into the priesthood, and it’s not hard to imagine that something might have been sexual in nature. There’s a feral quality to the way he looks at her that suggests he’s incredibly hungry, but he kind of stares at everything with that feral quality. (I’m reminded of the way Greta Gerwig talked about Timothee Chalamet and Saoirse Ronan as weirdly genderfluid when discussing why she’d cast them as Jo and Laurie in Little Women.)

The relationship also exists outside of societal propriety on some level, which also creates the sense that it’s about as queer as an ostensibly heterosexual pairing can get. Like, I’m not going to sit here and argue that this pairing is queer – it’s not. But it’s definitely designed to live in a grey area that society would frown upon should it be revealed. (Or maybe not. It’s not hard to imagine, like, Fleabag and the Priest getting together and everybody shrugging it off. The power of compulsory heterosexuality!)

No, where this scene is at its most queer is in its examination of power, of how on some level we want to be dragged by our noses to what we need. I remember in the long days before I came out, I used to imagine that someone would enter my life and see me and force me to become a woman. I wanted the choice taken out of my hands. I didn’t want free will anymore, didn’t want to be responsible for my own happiness and my own life. In some ways, society is set up to create effortless systems where people are told what they should want, and queer folks have always complicated that simply by existing. By saying I want to be a woman – no, that I am a woman – I’m fucking with something that others dare not even look at. Yet here I am.

But that’s the thing. Fleabag spent all her time between seasons one and two doing all of the things she was “supposed to.” Her life is better, but she’s not happier. Is she content? Maybe. But she’s also just as unsure as she always was. Longing for somebody to tell you what to do isn’t a desire solely of the religious. It’s a desire as human as needing food or oxygen. We are all of us tasked with the complicated reality of the way our own lives are, to some degree, dependent on our own ability to figure out what the fuck we want and then to find somebody who will listen.

Next week: This is a love story.