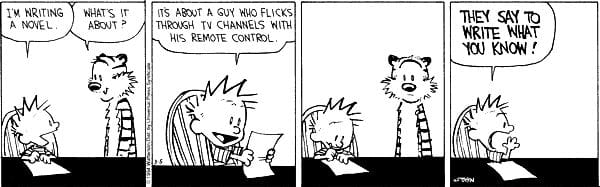

Episodes: Write what you (don't) know

Over the weekend, New York Times TV critic James Poniewozik, a friend, tweeted something that resonated with me: of all the pieces of writing advice you can give someone, "write what you know" is about the lousiest. (James's two tweets are here and here.)

It's easy to see why "write what you know" gets out there. When you're just a baby writer, you don't want to be writing stuff that makes no sense, and making sure you stick close to home base is a good way to be sure that happens. And yet, when we're kids, we more often than not write stuff that's just crazy and imaginative and made up. It's in no way writing what we know. It's just writing what we're excited about.

But "write what you know" is part of the mid-20th century movement to downplay anything but realism, in both fiction and non-fiction. These strictures have lasted so long that we're only just now beginning to really think about how artificial they are. And "write what you know" goes hand in hand with them.

For a long time, I amended "write what you know" to kids, telling them they should "write what you know to be true," which allowed for all manner of amendments to the original. If what you know to be true is that human beings will always betray each other in the end, well, you can tell that story in a quiet house along a suburban lane, in the Wild West, or on the surface of Mars in the year 2162. You can tell it as fiction, or as non-fiction, or as a humorous essay. And because you deeply believe in it on some level, it will sing with the passion of writing what you know.

But since I made the shift over to Vox, I increasingly think even that's not enough. Now, I would say, "Write what you know to be true -- and can you back it up?" The more time I spend reading young critics, for instance, the more it becomes obvious who has both a strong voice and some sort of knowledge base beyond the inside of their own heads, and those who just have strong voices.

The best critics, I'm increasingly realizing, are often also the best reporters, people who have a natural curiosity about the medium they cover, whether that leads them to talk endlessly with those who are immersed in it, or sends them on deep dives into the archives to see the hidden webs connecting the past and present to potential futures. And you can tell when someone is just sort of messing around, saying something that's backed up by nothing more than what's in their head. (Trust me: we all do this. We just try not to.)

"And can you back it up?" also applies to fiction. There, you don't really have to prove anything, but you do have to make sure that the audience follows your emotional and psychological swings, that they're painstakingly led every step of the way, given time to feel and think about the things you want them to feel and think about, even if that's causing them disorientation. The best writers are almost always the best at structure, at the sheer nuts and bolts of picking the right word and building the right sentence and crafting a paragraph with no fat on it. And that's tough to realize is the case, because that's work.

I was reading a piece recently by someone who was lamenting how they'd never gotten very far in their field of choice (it had nothing to do with writing, but it works well enough as a metaphor that I'm going to stretch a little bit), and the more I read the piece, the more it was obvious why: they were largely uninterested in doing the work it would take to make the next step up. In writing terms, they were all voice, no backup. They could talk a great talk, but there was nothing there to give that talk the added depth and weight it would need to really convince people.

I was there, to be sure, for a long time. I spent way too much of my 20s waiting for a door to burst open and someone to offer me a job. That was how it had always worked in my little town, where everybody knew everybody, and everybody knew I wanted to be a writer. But it didn't work in a world where nobody knew who I was, and it took me embarrassingly long to figure that out (again, most of my 20s). And even once I did, it took a long time for me to be ready, to really get clips to a place where they might actually sell. Arguably, I'm still in the long process of getting ready, of heading toward whatever the next thing is.

So if you want to write, really, really want to write, answer these three questions:

--What do you know?

--Do you know it's true?

--Can you back it up?

And after you've gotten past that, consider something else: What don't you know? Can you find out? Then you're off on some other quest entirely.

You'd be surprised how much these questions will make everything better in the end, even if they create lots of hard work in the short term. Good luck!

--

The newsletter unexpectedly took a week off last week while I was in Atlanta for work. We should be back on the regular schedule this week, but I am going to Austin for the Austin TV Festival, which might lead to more delays.

--

Episodes is published at least three times per week, and more if I feel like it. It is mostly about television, except when it's not. Suggest topics for future installments via email or on Twitter. Read more of my work at Vox Dot Com.