Episodes: What you learn not working

In case you haven't noticed, I'm a slight workaholic. I like to think I come by it honestly. My father loved to work, and if there's one thing he drilled into my brain, it's "If a job is worth doing, it's worth doing well." That, combined with a Type-A streak, has led to being the kind of perfectionist who can spend a whole day writing stuff at work, then turn right around and write an additional newsletter for no real reason whatsoever.

But the thing about my father was that he was a farmer, so from about November 15 through roughly April 1, he worked a lot, lot less than he did the rest of the year. Sure, he had chores taking care of our hogs during the day, but when he didn't also have to worry about crops, he had a lot more time to be there for our recitals and games and other crazy pursuits. And he always found a way to take a week in the summer to go on vacation, even if it was just to the Black Hills or something.

I am... not so good at this. Some of it, yes, is the way I'm like a chocoholic, but for work. But just as much is that two things happened in rapid succession to me in 2009. The first was that I was unemployed (by choice, though I picked a shitty time to quit my job). The second was that I was unemployed long enough that I got a little desperate to find something I enjoyed doing.

And then, thanks to the generosity of Keith Phipps, I suddenly had my dream job. (Seriously, I made a list of jobs I wanted in early 2009, and "TV critic at The A.V. Club" was number two.) I got stuck in a wacky feedback loop where I became convinced that if I didn't work all of the time, somebody would realize I was a huge fraud and fire me, so I'd have to take a job writing about medical devices in Oklahoma City (a job I very nearly ended up with when I was unemployed).

Plus, I was working from home. The nice thing about having an office job is that it develops a dichotomy between "work life" and "home life," one that you don't really get when you work from home. That means it can be hard to stop screwing around on the internet (perfectly acceptable "at home" behavior), but it can also be hard to stop writing TV recaps (not so perfectly acceptable "at home" behavior). In the early days at the AV Club, 16 hour days were my norm, and there was one time I worked 36 hours straight.

I say this not to brag, nor to suggest that anybody made me do this. As mentioned, I did this to myself. And I like to think the fact that I found a way to gradually decrease my workload over the years, and never worked a 36-hour stretch again, is a sign of... something. Possibly not personal maturity and growth, but definitely something. And, of course, working a lot got me to where I am today, which is a place I enjoy being.

But I still spent last week, when my wife and I were dealing with a long-planned surgery that we finally got the go-ahead for her to have, doing nothing but caring for her. I took work off, mostly putting up pre-written things that I had been saving for just such a week. I didn't take part in a daily writing exercise I do for a different writers group I'm in. And I didn't do this newsletter. I didn't write. I just watched TV. I played board games. I ate food I loved and watched movies. I slept and slept and slept and slept. I hung out with my wife, when she was conscious.

And the thing I realized as I did this was that there were parts of my brain that weren't getting the proper love and attention they needed. They were like plants without sunlight or water, withering away without me occasionally hanging out with them. Using work brain as much as I do leaves work brain feeling exhausted, the same as if you were doing a workout that only focused on, say, your arms or legs. You need to use the other muscles at some point, too.

This is, of course, basic self-care stuff. But it's easy to forget on the internet, and especially in internet publishing, where workaholics and those who never quit working are rewarded, almost as a matter of course. Vox Media, God bless it, has lots of great policies about work-life balance, but they only really work if you, the employee, decide to live by them. And I've been lousy at living by them for years and years now. And I'm just now starting to realize that's maybe made me a worse employee, writer, and editor than I could have been.

Because another thing that happened while I was out was that Gawker lost Hulk Hogan's lawsuit against it (over a sex tape the site published), with the jury awarding Hogan more than he had asked for. I think the decision is basically ridiculous, and I expect an appeals court to strike it down. But that it ever got this far in the first place is a testament to how getting so deep into your own work eventually creates a feedback loop where the only thing that satisfies you is the work and what you get out of it, be that traffic or acclaim or Twitter mentions. (I thrive on all three, thanks.)

The Hogan stuff wasn't even the most chilling portion of the trial. That was when the story of a rape victim's failure to have video of the incident pulled was recounted. The picture was clear: once you become part of a news story in that iteration of the site (but on the internet, really), you cease to be human and become a web traffic delivery mechanism.

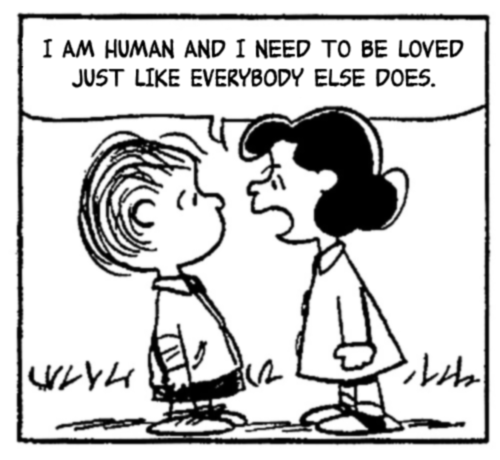

The level of insight I have into why Gawker published that tape is exactly zero. But I'm willing to bet that the consideration of whether the tape might have an impact on the livelihoods of actual human beings -- even those who worked at Gawker itself -- was swept aside in favor of how much it could benefit The Work. And don't get me wrong; I'm all about sacrificing things for The Work. But the second you place anything in a position of authority over yourself, be it a cult leader or Chartbeat, you can forget, so quickly, how to be human.

The most important lesson I ever learned about journalism was also, probably, the dumbest one. An instructor who would later come to hate me for reasons I never fully understood once took me aside and drew the inverted pyramid for me. Then he flipped it over and drew a little head and feet for it. "See?" he said. "It's just a little man."

His lesson -- find the human in every story you report -- doesn't apply 100 percent of the time, but it's one I think about often. What, for instance, is the human element of a bad review? Well, a completely savage one can feel like an unmotivated attack. Is there a way to be honest, but also be kind? Afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted, yes, but can we remember that on all sides of that story are people, not symbols?

The internet distracts us from this, because the internet rewards us with constant work that lets us forget to be people, too. Somewhere in there, we have to figure out how to live again, because it's in the process of living that the best work is done.

Or so I think. After a week of trying.

--

Episodes is published at least three times per week, and more if I feel like it. It is mostly about television, except when it's not. Suggest topics for future installments via email or on Twitter. Read more of my work at Vox Dot Com.