Episodes: What's in a show bible?

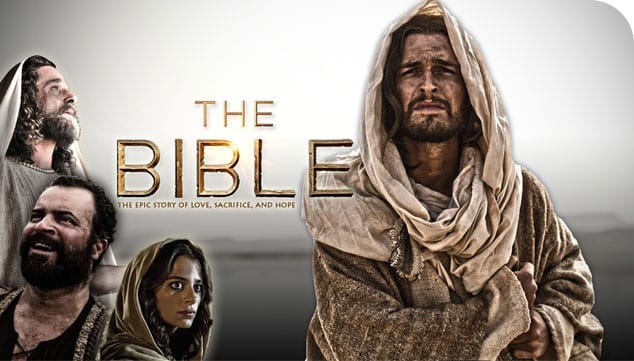

(The bible for The Bible was particularly complicated.)

If you read enough stuff about TV writing, or creating a TV show, you'll see a sorta cryptic phrase come up quite a few times: the show bible. But what is this thing? Where does it come from? How do you write one of your own?

The first question is the easiest thing to answer: the show bible is a document purporting to give a rough idea of what the show is, beyond the pilot episode. It will usually have character biographies and details on the show's world. In our era of serialization, it will probably have a sketch of how the creator thinks season one should go, with brief bullet points for where the series might go after that. But it's really up to the individual creator (because, yes, she writes the show bible).

But the last question -- how do you write one? -- there's no good answer for that.

Truth be told, there's no hard and fast template for writing a show bible. You can find a few simple guides around the internet, but for the most part, show bibles are as unique as the shows that spawn them. The (justly famous) True Detective show bible, written in a highly literary voice, is vastly different from the wonky bible for Battlestar Galactica. But if you read both, you instantly get a sense of what each show will be and why and what it will be going forward.

A friend of mine says that the show bible isn't about proving you can write. That's what the pilot script is for. It's about proving that you have a grasp on the problems inherent to running a TV show, especially the one you're pitching, and that you've thought through some workarounds to those problems. To use one example: the Freaks and Geeks bible -- an incredibly messy document -- contains one section where Paul Feig talks about the good business sense of putting on a show about teens in the '80s, because you can attract both the current teenagers of 1999 and their parents, who were teenagers in 1980. It... didn't really work out that way, but this section indicates to the network that he's already thinking about how hard teen shows can be to sell.

I'm a connoisseur of show bibles, reading every one I can get my hands on, and they're all incredibly different. Every so often, one of these will make its way into the wild, and the public will laugh about how, say, the creators of Lost didn't have 100 percent of their mythology mapped out, or they were promising to do standalone episodes or something, but this almost always ignores that the show bible isn't supposed to have every answer. It's, instead, supposed to convince the network you're not nuts. And by suggesting how Lost could have standalone episodes, that show bible immediately answered a question the network head would almost certainly have.

I've heard from people in the industry that bibles are becoming more and more important in an era when greener and greener creators are being trusted with TV shows. Yes, they can usually be paired with a veteran showrunner who can show them the ropes. But that's not going to be any good if they don't have a vision for the show beyond the pilot. A great bible will calm a lot of nerves, as it did when Nic Pizzolatto launched True Detective or Sam Esmail launched Mr. Robot. Neither had been a showrunner before; both showed they could make great ones via their bibles.

But here's the twist ending: if a show bible is too comprehensive, that can be just as scary to a network as well. A showrunner who thinks she knows exactly what's going to happen in every episode of her show, across 10 seasons, is a showrunner who is almost certainly going to run into the hard realities of an industry that's always, always changing. Many of the serialized dramas of the mid-00s -- the ones that arose in the wake of Lost and 24's success -- had these incredibly complicated ideas for where their shows were going to go, which were fleshed out in detail in their bibles, but they hadn't really thought about the steps on the way there. So they would often launch with a solid to great pilot (Flash Forward, The Nine, etc., etc., etc.), then flounder for several episodes because they'd been thinking more about season five than episode five. You can course correct for this (Fringe did, for instance), but it's hard to do once everybody from the network to the lowliest staff writer has an idea of "the template."

Anyway, if you are at all a TV fan, I invite you to google show bibles. There are a bunch of them here, and taking a look at them will probably give you a stronger sense of why some shows turn out the way they did and why. I've always found it instructive, at the least.

---

Our Friday mailbag feature is a lot of fun! Please email me your questions over the course of the week, and I'll pick a few to answer. I'll always answer at least three per week, unless I just don't have the material. For ease of inbox search, please put "mailbag" somewhere in the subject line of your email. Thanks!

--

Episodes is published three-ish times per week, and more if I feel like it. It is mostly about television, except when it's not. Suggest topics for future installments via email or on Twitter. Read more of my work at Vox.