Episodes: Empires of the air, OR Your big friend in the Midwest

Immediately after finishing Kelly Reichardt's achingly melancholy new film Certain Women, which tells the stories of three different women in small town Montana, whose lives intersect in unexpected ways, I headed over to Vox, to read my colleague Alissa Wilkinson's interview with Reichardt.

In it, I found a truism about the great empty portions of my country that I had never quite thought about in that way. Wilkinson asks Reichardt about why her films feature so many characters simply sitting and listening to the radio. In response, Reichardt says:

And it’s another level of community: strangers calling in and connecting over the airwaves. A voice on the radio that becomes like a friend, that tells you not to go out in the snow. The community over the radio, which I suppose happens less these days but it still exists.

(Don't worry. I'll come back to this.)

Certain Women has been criticized in some corners for being too slow-moving, too meandering. I can see where you might think that. It's certainly a movie where not a lot "happens." It takes place in the interiors of the women's heads, and since they're played by Laura Dern, Michelle Williams, and newcomer Lily Gladstone (with able assists from folks like Kristen Stewart, Jared Harris, and James LeGros), those interiors are beautifully delineated.

But a Reichardt movie is never a film you go to for a pulse-pounding plot. Indeed, the Dern portion of this film -- in which her character goes to talk to a client of hers who's taken a hostage -- is about as close as the director has ever gotten to something like a crime drama, with big, dramatic stakes. (When you see the film, you'll realize how amusing this statement is.) And certainly most of the folks who have criticized the film will know that. Maybe Reichardt just isn't for them.

While Certain Women isn't my favorite Reichardt film (that will probably always be Wendy and Lucy, though Meek's Cutoff is tremendous, too), I do love the way she captures certain types of lives that we don't really see up on screen with the verisimilitude they deserve. There's an almost documentary-like fascination with, say, the way Gladstone's characters (a ranch-hand) does her chores, and Reichardt marks the passage of time in opening the barn door for the horses, then closing it again at night. She captures the rhythms of these lives with a real precision.

And as she points out in her interview, part of that precision involves listening to the radio. A lot. Sometimes just to get information. Sometimes in need of a particular piece of community news (especially if there's a blizzard and school might close). And sometimes just to hear another human voice in a day when you might not realistically expect to hear one.

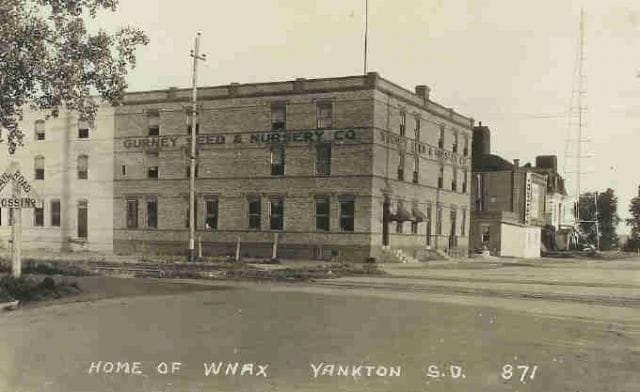

Of all of Reichardt's realizations about rural areas, this might be the most piercing to me. I don't remember a day in my life when the radio wasn't on, tuned to WNAX (your big friend in the Midwest, 570 AM). We'd listen to the morning show guys read the farm report and joke around about the weather or sports, and after the kids were off to school, it would be time for a show called The Neighbor Lady, in which a woman named Wynn Speece would share recipes and homemaking tips. The afternoon mostly featured country music, and the night was for sports -- Twins baseball games or high school basketball and football. Weekends featured church services and other programming (including some show that was pretty much just fiddle music).

That radio is so important when you're out in the middle of nowhere, with no real guarantee of Something Else coming to break your monotony. A favorite song becomes a way to get through your chores, and a trusted DJ or personality feels almost like a friend. And if you're driving somewhere through the night -- as you often are in a rural area -- the high-pitched whine of the AM station, layered over some program or another (often Coast to Coast AM) is everything separating you from the oblivion of that darkness.

As I write this, I know the radio in my dad's shop is on, turned to oldies, so the cats who live in the shop will have the sound of voices. He'll have it on throughout the day, then just leave it playing when he heads back to the house. I can remember summer days spent at my grandmother's house, as she went about her chores and listened to whatever Wynn Speece was up to that day. And I think of my father-in-law, whose long hours in a local pharmacy were never complete without radio to join him.

I think, in some ways, this is why it's been hard for progressives to understand the rise of conservative talk radio. Stations like WNAX, which you came to think of as trusted friends, discovered they could pull in even better ratings with syndicated talk shows, and they simply started replacing their old shows with right-wing talk, the louder the better. And in rural areas, hey, what were you going to do? Stop listening to the radio?

I fear sometimes that the radio station as community outpost is slowly disappearing. But go out driving in the middle of nowhere at night. Turn your radio on scan. See what pops up out of the dark, which voices are there to guide you back where you belong.

--

Episodes is published three-ish times per week, and more if I feel like it. It is mostly about television, except when it's not. Suggest topics for future installments via email or on Twitter. Read more of my work at Vox Dot Com.