Episodes: "A Wonderful Guy" from South Pacific

(We're talking about show tunes this week, because I feel like talking about show tunes this week. You can nominate some of your favorites! I probably won't write about them.)

Since I received it as a Christmas gift last year, I've kept Stephen Sondheim's complete, collected lyrics close at hand, for whenever I need something to flip through at a moment's notice. If you haven't purchased this set yet and enjoy musicals even slightly, it's a must own. You don't even have to like Sondheim! He has so much to say about other composers and aspects of a life in the theater that you'll find plenty to enjoy. (Of course, liking Sondheim is a definite plus.)

One of the things I have been most struck by in reading the book, however, is the way that Sondheim talks about rhyme structures in musical theater. In essence, he argues, you need to have rhymes and not just false rhymes or "clever" rhymes. They need to be as true of rhymes as you can make them. If you're going to say "cat," in other words, you'd better rhyme it with "bat" or "rat" or "that," not baccarat or atarunjuat or some other word that seems like it rhymes but actually drifts off in its own direction.

Sondheim's reasoning for this is sound, of course. He argues that the audience for a musical needs to follow the lyrics to follow the story and/or character arcs. And true rhymes help with that. Your ear knows when it hears "cat" that "bat" is right around the corner. And if it isn't, you get thrown, then spend just long enough trying to suss out the not-quite-rhyme you just heard that you miss some of what comes next. Without being able to follow the rhyme scheme, your brain starts to fall behind, and you can become hopelessly lost. Sondheim has a reputation for being clever, but read his lyrics, and you'll see that he usually follows an at least somewhat strict rhyme scheme.

This, to some degree, is why popular music (and especially modern pop and hip-hop) has struggled so much to make incursions into the theater. Hip-hop is a form completely built around lyrical dexterity and cleverness, where half the fun is your brain being surprised by little verbal fireworks explosions built into the rhythm of the piece. But that's hard to make work over a two-act show (though Lin-Manuel Miranda is the exception that proves the rule)! Similarly, rock music has struggled on the stage, because rock lyrics are often about feel and sweep, rather than anything concrete. Once rock music starts to rhyme precisely, it's no longer rock music, which is why so many so-called "rock operas" feel far more like the latter.

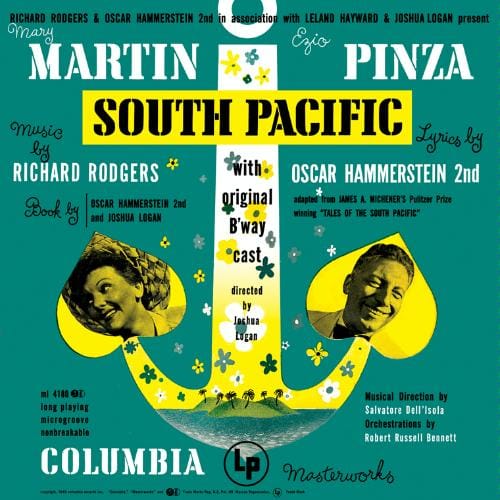

I use all of this as a lengthy preamble to talk about Rogers and Hammerstein, who are, of course, unavoidable in this context. Oklahoma was the show that changed everything, and Carousel is their best show, but South Pacific won them a Pulitzer, and it was the one I had the most fun starring in in college, so you're going to get to hear about that.

Aspects of the show have certainly dated poorly, but at its core, South Pacific has a lot of truth and beauty that forgives the very 1940s things in its plotting (like the whole subplot with the beautiful teenage Polynesian girl, which ick). And it also, as with all lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II, has absolutely impeccable rhyme schemes. I was originally going to talk about "There Is Nothing Like a Dame," which keeps rhyming "dame" with "dame" in a way that somehow expertly conveys pent-up sexual frustration, but then Crazy Ex-Girlfriend (a wonderful show you should watch soon) kept beating "A Wonderful Guy" into my head, and here we are. (Let's listen to Kelli O'Hara's version, shall we?)

Obviously, the rhymes in "Wonderful Guy" are airtight, but let's look at one of the verses anyway:

I'm as corny as Kansas in August

High as a flag on the Fourth of July

If you'll excuse an expression I use

I'm in love, I'm in love

I'm in love, I'm in love

I'm in love with a wonderful guy!

There's only one obvious rhyme here: "July" and "guy" rhyme, more or less. But look at how Hammerstein builds out lots of other lyrical signposts to lead us through the material. "August" is followed by "July." They're not only both months; they're both months in the heart of summer. (Later, he'll work in May as well.) Then both "corny" and "Kansas," as well as "flag" and "Fourth" start with the same sounds, building out little islands of alliteration that give us safe ground to stand on. (It also doesn't hurt that they're all rich with Americana in the images they invoke.) Then, finally, we have the internal rhyme of "excuse" and "use," which helps build into the endless repetition of "I'm in love," which only serves to build to the verse's emotional high point. Later, Hammerstein gets away with the word "bromidic," which most of us would probably have to look up, because he pairs it with "bright," which we all intuitively understand.

There's so much thought in every word chosen in this song. I get that thinking about lyrics in this fashion can make them feel like a math problem, but sometimes, doing a math problem is as fun as working on a creative writing assignment. There's a beauty to art that is rigidly, rigorously structured, which can be easy to miss until you start pulling it apart.

"Wonderful Guy" is kind of a crazy song when you start pulling it apart. (It's about a woman celebrating giving up her independence for a man, for one thing!) But the combination of Rogers's music with Hammerstein's perfectly deployed words means it doesn't feel like that at all. It feels, instead, like the first blush of new love, like the moment when you realize that your whole life is going to change because of a person you just met. Every song in a musical is some mode of transportation, taking us from one place to another in the narrative of the story. And "Wonderful Guy" works so well because it's a rocketship.

--

Episodes is published daily, Monday through Friday, unless I don't feel like it. It is mostly about television, except when it's not. Suggest topics for future installments via email or on Twitter. Read more of my work at Vox Dot Com.