Toward a definition of "Egg Cinema"

TO BEGIN WITH:

I don't love the term "egg," which I broadly define as "a trans person before they have self-accepted." (You can see a bunch of memes about being an egg here.) It is a useful term, since it explains a concept we need a word for. Yet it often also becomes a trap lots of, uh, eggs fall into. Once you get to a point where you are self-aware enough to accept that you might be somewhere under the trans umbrella, you can put off going any further than that point a long time by simply having a word that describes you.

Furthermore, the term "egg" is sometimes applied too liberally to a lot of people who might otherwise be dissociating for some other reason. Like, yes, I've met seeming cis men who had a distant, disconnected look in their eyes, one that felt a little like their real self was floating behind their bodies like a balloon, but I've had enough trauma therapy by now to realize there are plenty of reasons you might end up dissociating your way through life. Not all of them involve an acute case of gender.

Finally, it's really gross, imo, to speculate about if someone is an egg! Unless you're in private company with a handful of other trans friends, and then the topic is just going to come up, I'm sorry. It's unavoidable!

THAT BEING SAID:

There are certain works of art that can best be described using the adjective "eggy." I saw the film Being John Malkovich again last week, and while it remains one of my favorites ever made, Christ, what an eggy movie! I had similar feelings about Yorgos Lanthimos's new film Poor Things. As I thought about what I meant by this, I realized I needed a definition.

THEREFORE:

Let us define the egg cinema.

First: Some qualifiers

"Egg cinema" heavily seems to imply "films made by eggs," so I have to hasten to say, no, I do not think Yorgos Lanthimos is an egg. Yes, some films I would call "egg cinema" are made by eggs, or at least trans people on the verge of self-accepting. The Matrix springs readily to mind! Yet the closer you get to grappling with your own gender, the harder it is to make a movie that falls under the "egg cinema" umbrella. The Matrix Resurrections, for instance, is not a film I would consider egg cinema.

Indeed, I would argue most egg cinema is made by cis people who accidentally stumble into a field rife with Gender Interpretations and Trans Readings. For instance, several Stanley Kubrick films have substantial overlap with egg cinema, as does Steven Spielberg's A.I. I never like to assume people's genders, but I do think Kubrick and Spielberg are probably cis. Have you seen Jaws? That might be the most cisgender film ever made!

If I were to briefly define egg cinema, I would say: a film that is aware of the prison that is the gendered human body but unsure of what to do about that prison.

For instance, Greta Gerwig's Barbie definitely fits the first half of that equation, but it's also a film that tries to propose a way out of the thicket. Therefore, it's not egg cinema. For a film to be egg cinema, it must capture the experience of being an egg, of feeling a little bit at a loss to explain why everything feels off somehow.

With all of that in mind, here are five ways you might know you are watching EGG CINEMA. Not all films under the egg cinema umbrella will fit all five categories, and some might not fit any at all. This is, primarily, a vibes-based assessment. But if you are, like, "Wow, this movie about being John Malkovich sure seems like it's crying out for a trans reading!" then let this list of signifiers be your guide! If it hits just one, maybe it's not egg cinema. If it hits three or four, though... consult your local trans film scholar.

Also, to be clear: Every movie I talk about in this newsletter, I like. Bad egg cinema exists, but it's usually... really bad.

Also, to be clear: This is all written about from a trans feminine perspective because that's my experience. There are plenty of films I'm sure trans guys or non-binary folks would argue are egg cinema, but I'm not going to be able to speak to that. Still, I'd love to read that piece!

Consider becoming a paid subscriber: For as little as $5 a month, you can support this newsletter and help keep it rolling. Paid subscribers get a weekly post on Fridays, access to comments, access to my Andor recaps, and a link to the Episodes Discord server. There will be some other fun treats along the way. Click the button to learn more!

A checklist to answer the question: Are you watching egg cinema right now?

1. The film is aware of gendered power dynamics but only in the most cursory of ways. For example, Being John Malkovich knows that Craig, its protagonist, played by John Cusack, is a piece of shit who takes his spouse, Lottie (Cameron Diaz), for granted and openly lusts for his business partner, Maxine (Catherine Keener). It's also aware that both Lottie and Maxine are limited in their ability to maneuver socially by their seeming genders. (To clarify something: Lottie briefly comes out as a trans man, then seems to un-come out later in the film. I will deal with this in greater depth in a second, but for purposes of this argument, it's worth noting for the entire running time of the film, the world perceives Lottie as a woman.)

Similarly, Poor Things knows that the world too often only has use for women as either beautiful innocents or vessels to have babies. Yet after developing this theme fairly well through its first half, it then... mostly hangs out in that space. It's like the film knows how hard life as a woman can be, but it hasn't really thought beyond that core idea to probe at anything new.

For a lot of trans feminine eggs, the received wisdom that "being a woman is so hard" becomes a sticking point, leaving them forever on the precipice of coming out. Being aware of your own womanhood but not wanting to do anything about it because you are aware patriarchy exists but don't want to think about it in any real depth is a distinct trans feminine mood, and a lot of egg cinema captures it.

2. Yet the film also fetishizes gender performance, though usually in ways that read more as envy than anything romantic or sexual. Craig in Malkovich is obsessed with Maxine. He's deeply intimidated by her, immediately infatuated with her, and intently focused on getting her to be his. Yet the film possesses just enough detachment from him for viewers to realize he's treating her not as a person but as an object. Craig doesn't just want to sleep with Maxine; he wants to possess Maxine as a means to become her. Craig wants her confidence. (You'll note that Maxine is the one major character in the film who never actually gets to "be" John Malkovich. The one time she goes through his portal, she gets shunted into his subconscious.) Another Charlie Kaufman-driven example here might be how Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind presents Joel's fascination with Clementine.

On the opposite end of this spectrum, lots of people wrote about how the original Matrix presents its characters as, simultaneously, fetishized and just a bit sexless. This quality particularly comes through in Trinity, but it could be just as easily applied to Neo or Morpheus. The envy here is for a world where gendered performance isn't considered so obligatory, where all can be as androgynous as they would like to be.

The line between envy and attraction is complicated and not always easy to pin down. There's a reason so many queer people have to puzzle out whether an object of attraction is someone they want to fuck or want to be. Egg cinema can get lost in the hazy middle ground of that "or," never quite understanding just what it wants but knowing that it's somewhere just over there.

3. The body is, ultimately, a prison one cannot escape, and you just need to learn to accept its confines. Lottie has a huge revelation after the first time through the portal that allows one to be John Malkovich: Lottie is a trans man and can only self-actualize by going to his allergist(???) to ask for medication to begin the process toward "sexual reassignment surgery." The film treats this desire of Lottie's as patently absurd, and by the end of the film, gender has defeated Lottie Schwartz, who seems to once again live life as an apparently cisgender woman, having made peace with a gender assigned at birth. That Lottie might be a lesbian is treated as quite natural – why wouldn't one want to escape the company of men?? That Lottie might be a man underneath it all is treated as farcical. Lottie's body is Lottie's body. Any attempts to do anything about it are doomed to fail.

To toss in a TV example, Joss Whedon's short-lived Dollhouse involves a world where consciousness has been liberated from the body and turned into raw data that can be uploaded to any other form. Our protagonist, Echo, is a "doll" who can have any number of other consciousnesses loaded into her body. The invention of this technology causes the apocalypse. Once a person is no longer confined to the body they were born into, existence starts to fray around the edges, and one of the core mysteries of the series is who Echo "really" is.

The core experience of being an egg is grudgingly making do with the body you have and treating any attempts to make it more in line with your conception of yourself as doomed to fail. Why would you ever try to be someone else when you have to be yourself? Your body is your body is your body, and, more importantly, you don't get to decide what to do with it.

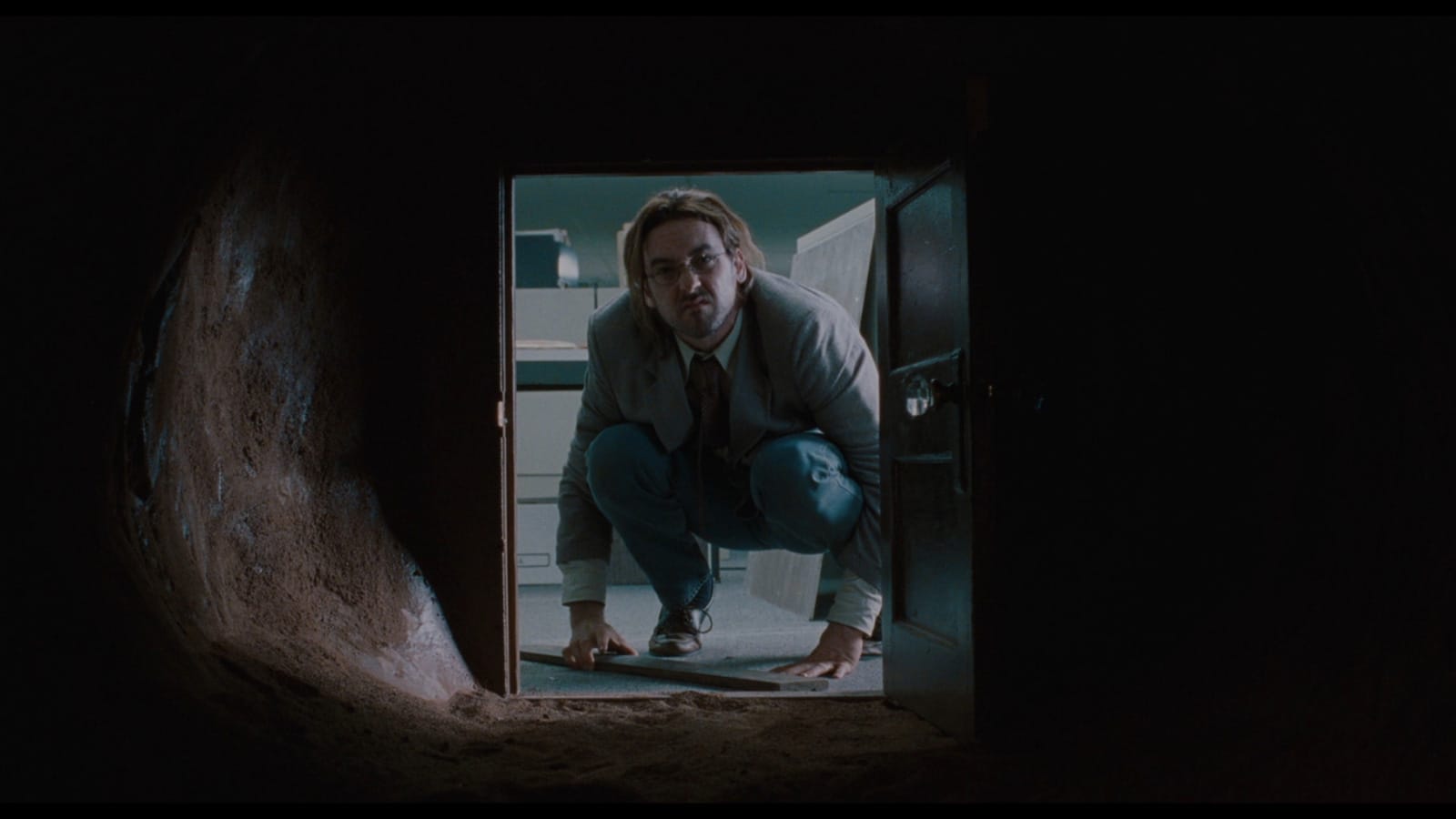

4. There is some sort of portal or door into another world where the rules of identity are different from your own. In Malkovich, the presence of the portal is quite obvious. When you go through a tiny door, you are sucked into the brain of John Malkovich and able to see the world through his eyes. Easy-peasy! Or consider James Cameron's Avatar, in which you go through a neural network to enter an alien body. Similar idea!

Yet in many other films under the egg cinema umbrella, the portal is more understood than anything else. Midsommar, a film whose trans reading I have written about before, takes the characters out of their normal lives into a different world, down a long stretch of rural road that has a distinctly portal-like feel. Once there, the various ways in which they define themselves are tossed asunder, and our protagonist finds some piece of herself that went missing in the highly gendered lives of the Harga.

A fairly common pre-coming out trans experience is the longing for some sort of door into another life where your entire self might shift and change. To be clear, plenty of cis people long for a door into another life, too. There are a lot of reasons to want one! But combine that desire with a motivation driven by a struggle with gender or identity, and you might find yourself in egg cinema territory.

5. Mainstream critics and audiences talk about how inventive the film is. I will never forget the experience of seeing Being John Malkovich for the first time, going to read reviews of it, and learning that everybody was talking about how wild and original it was. Yes, I could understand that in the vast universe of films that had ever been made, Malkovich was pretty unique! But to me, it also captured something fundamental about how I saw the world. The same thing happened with The Matrix and nearly every other movie I've talked about here. I saw them and thought, "Yep, it's just like that!" and people were, like, "Such wild invention!"

The thing about egg cinema is that, uh, cis people usually don't think about this stuff as often as trans people do. (Maybe you are a cis person, and you think constantly about gender, but in that case, I would recommend you consult a specialist.) So when a film comes out that brushes up against these ideas – accidentally or intentionally – cis people can lose their fucking minds.

To be sure, exposure to egg cinema can be a great thing for the cis, who should probably think more about how society polices their gender and bodies in ways that might seem invisible to them. But the way even eggs who later come out usually get to considering those ideas is via occasionally laborious metaphors.

When I saw Malkovich and it just made sense to me, it was because it had stumbled over a trip wire in my own brain in its attempt to present the wildest, most unusual story imaginable. I followed that trip wire back to its origin point and discovered some cool things about myself.

The value of egg cinema, even for The Cis, is in how it asks us questions about what it means to have a body and what it means to live in the world with that body. Whether it gets there via the filmmakers sincerely thinking about their own gender or just trying to put interesting stuff up onscreen is immaterial. It got there, and if you let it take you there, you might figure some things out about yourself too.

The free edition of Episodes is published most Wednesdays, and the subscriber-supported edition of Episodes is published every Friday. It's written by Emily St. James. If you have suggested topics, please reply to the email version of this newsletter or comment (if you are a paid subscriber).

Member discussion