The surprisingly conservative core of Boy Meets World

The '90s sitcom, often lauded as progressive and ahead of its time, was all about lauding middle-class whiteness.

(Welcome to the Wednesday newsletter! Each week, I’m publishing a new pop culture essay from a freelancer. Remember: Your subscription fee helps me pay these freelancers for their efforts! This week: Madison Davis on the not-so-progressive core of Boy Meets World.)

Across its seven-year run, Boy Meets World went through multiple theme song changes, common in sitcoms of the time. In season four, Cory Matthews, the “boy” of the title, bounds down a flight of stairs of his house to join his friends in a red Chevy. An upbeat rock instrumental plays as the gang drives down the road. The car’s mirrors and the blue sky reflect clips of the show’s past. The cast members smile wistfully at the clips, as if daydreaming of the scenes themselves — their own true memories.

Here are two boys enacting an elaborate handshake routine. Here is a little white girl, laughing and blonde. Here is a man holding his wife. Here is a teen boy gazing into the eyes of a teen girl. The memory-scenes tell us that this is a show about love, a show about friendship, about sons and daughters, husband and wife. In the 21 seconds that the theme song lasts, we’re shown that these teens are already plagued with a happy nostalgia. Together they drive, the past propelling them onward to creating new memories. A new millennium is just a few seasons away.

By some regards, the Matthews are a traditional, middle-class, American family. That tradition is explicitly one of whiteness and heterosexuality. They prefer “Merry Christmas” over “Happy Holidays.” They are presumably Christian, despite the Jewish heritage of lead actor Ben Savage. They reside in Philadelphia, a city not nearly as racially homogeneous as shown on screen.

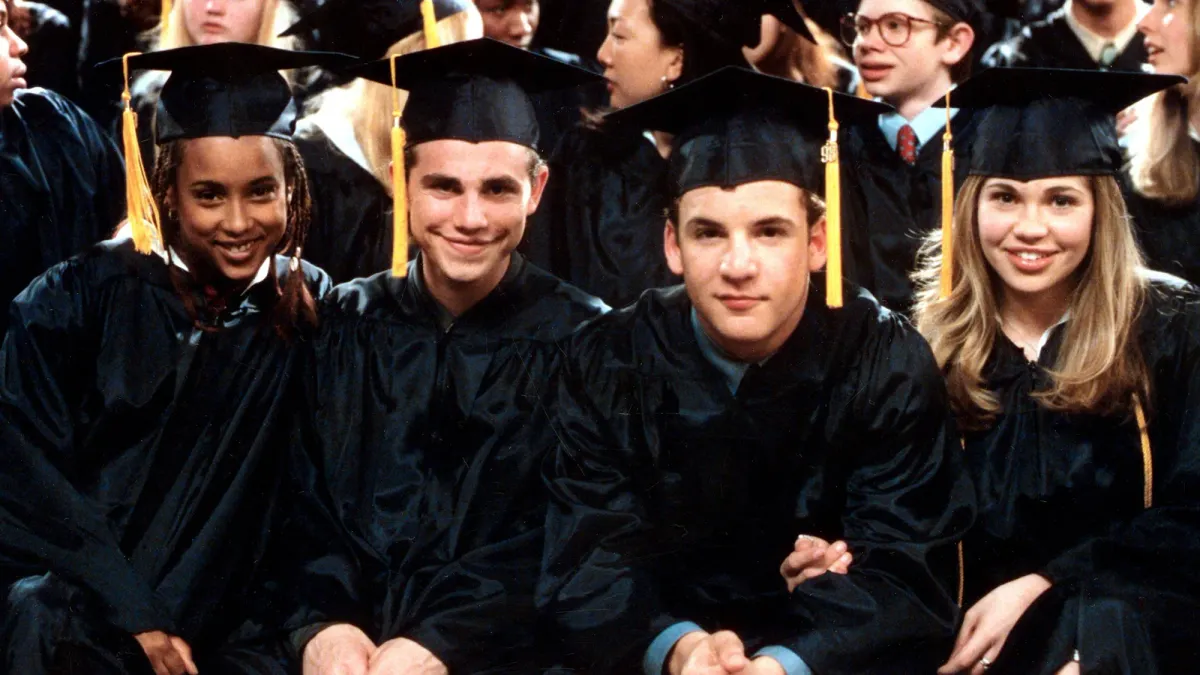

Boy premiered in September of 1993, a year-and-a-half before I was born. I can’t recall a time when I didn’t know the name of the show or its main characters — protagonist Cory (Savage); his older brother, Eric (Will Friedle); his girlfriend, Topanga Lawrence (Danielle Fishel); his best friend Shawn Hunter (Rider Strong); and his next-door neighbor and lifelong teacher, Mr. George Feeny. I have vague memories of sitting in front of the T.V. with my older sister, watching ABC’s TGIF lineup but it was after the show ended in 2000, that it became a lifelong staple for me via syndication.

Despite recent classifications as “woke” by some, Boy Meets World always centered the perspective of a conservative white middle-class. Though it was understood that not everyone fell within the series’ narrow parameter, differences were often subtly painted as unfortunate deviations to be corrected. Cory’s life stands in stark contrast to leather-jacket wearing heartthrob Shawn, who lives in a trailer park with his frequently unemployed and absent parents. Where the Matthews represent the hope of the nuclear family, the Hunters show the danger of its breakdown. Through Cory’s family we see the advantages of middle-class security, which the show subtly argues are brought only by hard work. Via Shawn, we’re warned about the effects of poverty, such as inherited alcoholism or joining a youth cult (yes, this actually happened at the end of season four).

The conservative core of Boy Meets World

Boy Meets World was more concerned with conveying values than it was replicating reality. That quality allowed for a playfulness with the sitcom form. “By the fourth or fifth season, we just started to get more and more meta,” Strong, who played Shawn, said in 2013 during a reunion panel ahead of the preview of spinoff Girl Meets World. “Our show was weird, you know? Our show did weird things. That’s turned out to be the lasting value of the show, I think,” Strong said in 2019.

It's true that the absurd humor appeals to me now as much as it did as a child. Storylines that called attention to themselves, in particular, stuck with me. One particularly meta episode involved Eric discovering he is a talented actor. He is offered a part in a TV show called Kid Gets Acquainted With The Universe, which focused on the experiences of Rory (played by Savage as a tyrannical actor named Ben Sandwich). With its easily digestible 20-minute episodes, it’s easy to see why Boy Meets World recirculated in syndication long after its finale.

But the self-aware jokes never teetered into self-critique or examination. Unlike the current growing genre of TV that aims to satirize the entitled egotism of whiteness through white-centered narratives (White Lotus, Succession) with varying, debatable success, Boy Meets World was comfortable in its narrow focus and protective of its conservative conventions.

Angela Moore, Shawn’s first long-term girlfriend, played by Trina McGee, was the only recurring Black character to last more than a season on Boy Meets World. She was the earliest reason for my continued loyalty to the show.

The charm McGee brought to Angela was a welcome presence. As a child, I was mindful of the way her hair changed from episode to episode without comment or wandering white hands begging to touch it. She wasn’t a caricature of Black femininity. She portrayed the confidence and humor I saw in my sister, my cousins, and myself. At one point, she tells Cory that they were never really friends and turns away from him, leaving him stunned. The scene is intended to evoke surprise or even sadness, but I laughed at the flippancy of her delivery, a tone that conveyed, “Boy, get out of my face.”

Race is rarely addressed on Boy Meets World and never within the context of Shawn and Angela’s relationship. McGee’s own feelings about the depiction interracial couple may have contributed to this in some part. During the airing of the show, she wrote an op-ed for the LA Times in which she argued that the colorblind love shown on television had the potential to help usher in a more racially harmonious future.

Unlike Cory and Topanga, however, Shawn and Angela didn’t receive a happily ever after ending. In fact, McGee is the only cast regular who doesn’t appear in the series finale. It’s a decision Boy Meets World co-creator, Michael Jacobs stands by, claiming that to keep them together would have been dishonest. “Forget the color. They never meshed. Every episode was about why Shawn and Angela would not sustain,” he said in 2018. “There can only be one Cory and Topanga, and if Cory and Topanga and Shawn and Angela succeed, it lessens what I always thought was the mantra of the core show.”

The resolve that Shawn and Angela weren’t destined for each other wasn’t unbelievable but their union wouldn’t have been any less realistic than Cory and Topanga’s childhood sweethearts to newlyweds arch. It’s telling that Jacobs’s quote suggests the poor kid and the Black girl couldn't represent the “core mantra” in a show about aspirational whiteness. And Jacobs’s comments echoed in my mind when in January of 2020, McGee tweeted about the racism she endured while filming BMW as well as during her guest spot on the 2014 spinoff Girl Meets World. The allegations included being “called Aunt Jemima” as well as a “bitter bitch” by castmates.

Called aunt Jemima on set during hair and make up. Called a bitter bitch when I quietly waited for my scene to finish rehearsing that was being f’ed up over and over due to episode featuring my character. Told “ it was nice of you to join us” like a stranger after 60 episodesJanuary 12, 2020

“I couldn't seem to shake the hurt of some words and situations that were said not only on that set but on most of the sets that I’ve worked on,” McGee later said in an interview with Yahoo in July 2020, explaining her choice to speak years after the incidents occurred. If it could be argued that Boy Meets World succeeded in creating a colorblind love story the series had failed to deliver on its promise of blanket equality where it mattered most: in the treatment of the Black person occupying the role. Even the hair changes I loved so much were marred as McGee revealed that she’d spend entire nights before a day of shooting doing her hair because there was never a stylist who could.

The mask never comes off in older sitcoms, because it was never on to begin with

The ability to poke fun and pull at the seams of older sitcoms stems, in part, from the time in which they were created. Since Boy Meets World’s first airing, television has fashioned itself for binging and replay. On Netflix and Hulu, entire series are released with the awareness they may be watched in one’s day worth of indulgence.

The combined power of the internet and tech advances has also reframed audience viewership. When Jacobs convinced ABC to conduct an online poll with viewers to determine whether or not Topanga and Cory should marry by the series’ end in 2000, the internet itself was still novel. Now, the Algorithm — the present moment’s designation for an all knowing entity that specifies a collective awareness of being manipulated by power — tracks and aptly predicts taste in, well, everything (much to our chagrin). Streaming site originals often have the air of being developed in relation to online discourse, tepidly covering the most basic tenets of representation and liberal politics, all the while delivering stories as flat and uninspired as the debates they seek to mimic.

Beyond nostalgia, perhaps the allure of dated sitcoms is that when watching, there's no waiting for a “mask-off” moment, because the mask was never on in the first place. The stakes are lowered in this sort of viewing, providing an ease not always afforded in contemporary white-run and centered TV shows that insist they’re in on the joke without fully understanding the object of ridicule. I’m certainly not yearning for a return to Happy Days, but it’s important to consider that a simple acknowledgement of social issues is not inherently more investigatory or a sign of progress than the presence of a singular non-white person in the cast, like Angela on Boy Meets World.

“I said it way before I knew any of the world’s changes were about to happen,” McGee said of her January 2020 tweets in her Yahoo interview. “I do believe in divine timing.” McGee was referencing the protests against the murders of Black people by police that had begun weeks prior and quickly spread across the United States and around the world. America’s Racial Reckoning headlined the pages of major media outlets in admission that we were as far as ever from a post-racial utopia or the colorblindness depicted in ‘90s sitcoms.

The American Dream style ethos of Boy Meets World was always at odds with the progressiveness it has sometimes been lauded for. To position whiteness as the default and the norm to be protected necessitates the perpetuity of racial disparity, even if offscreen. This contradiction is mirrored in the singularity of declarative headlines implying America is finally waking up to its racism, instead of situating the uprisings of 2020 within a consistent lineage of protests in response to racial violence.

In a country founded on generations of genocide and one that may have forever bound a people to the category slave, we are always on the cusp of the beginning and an end. Centuries of resilient combat against, survival in spite of, joy found away from, prove that we have always been in the midst of a reckoning.

Episodes is published three times per week and edited by Emily VanDerWerff. Mondays feature her thoughts on assorted topics. Wednesdays offer pop culture thoughts from freelance writers. Fridays are TV recaps written by Emily. The Wednesday and Friday editions are only available to subscribers. Suggest topics for future installments via email or on Twitter. Read more of Emily's work at Vox.