You are not smarter than the art you critique

For as long as I was working as a critic, people who wanted to be critics – or just thought it would be fun to write criticism – would ask me for advice on how to write great reviews. I'd usually say a bunch of bullshit about how criticism is in conversation with both the art and the reader, a bridge between the artist and the audience, meant to serve as an interpretive lens. Eventually, their eyes would glaze over, and they would realize I'm terrible at succinctly explaining anything.

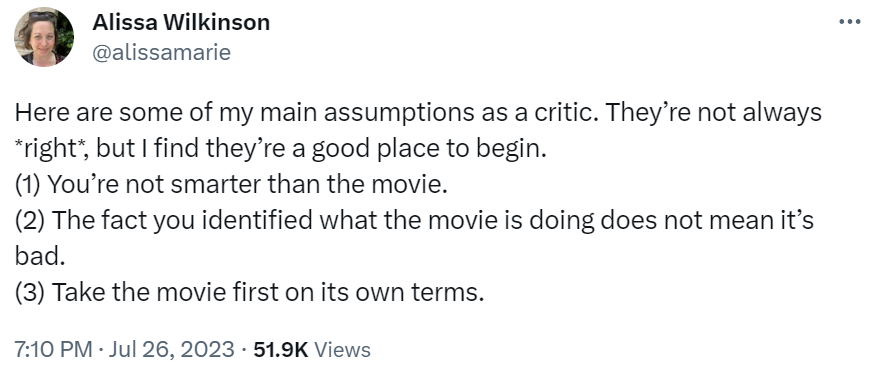

Anyway, then my former colleague and long-time friend Alissa Wilkinson put it succinctly so I didn't have to:

(Alissa's thread goes on from there and is worth reading in full, while Twitter still exists as some shadow of itself.)

"You're not smarter than the movie" is now the thing I would say when people asked me for advice if people still asked me for advice on how to write criticism. Because a lot of people come to love criticism via reading vicious, funny reviews by critics who run the gamut from Roger Ebert to Esther Rosenfield, the assumption they make is that criticism equals dunking on something. This attitude is not new. Negative reviews have possessed an element of performative smugness as long as we've had negative reviews. (Read what the Greeks had to say about each other!) Read enough bad reviews by Ebert or Rosenfield or [insert critic you like here], and you'll find that even their harshest reviews contain a deep, abiding love of the medium they're writing about and a willingness to be surprised by even the filmmakers they've most disliked in the past.

Consider, for instance, Ebert's review of Mulholland Drive or Rosenfield's review of Oppenheimer, both of which engage with why they continue to wrestle with filmmakers whose work they have not previously liked. Sometimes, a filmmaker you don't love – or even outright hate – will come up with a film you adore because that's how art works. It's a weird mind-meld, and when you're in the zone, it feels incredible. When you're not, it feels just a little repulsive.

The mistake I see a lot of new critics making is to assume that if they don't like a thing, then its existence was some sort of accident, rather than a series of deliberate choices by the artist that led to the thing they disliked. It's far easier to decide that you know better than the artist, that they are here to listen to you about where they failed, than it is to consider that the choices they made are just not choices that spoke to you. To be clear and to repeat myself slightly: You do not have to like those choices. You do have to engage with them. You have to take the work seriously on some level, even if you're going to write an excoriating review of it. Otherwise, you just end up being mean. Being mean can be fun in short bursts for every critic – god knows I've written mean reviews – but it's ultimately a dead end. Once you're too far down that road, you box yourself in to a jeering self-certainty.

As Alissa would have it: You are not smarter than the movie.

(Sidebar: One of the big reasons I left criticism is because I felt myself starting to get sour and mean when I didn't like things. Some critics do their best work in this space, but I don't know who was served by me writing stuff like this about This Is Us, a show I had tried to engage with before but mostly just seemed angry about in the linked piece.)

Where I think this natural tendency in critics dovetails with the Problems of Our Modern Age comes from sites like TV Tropes. These sites are entirely fine in a vacuum, and I use them semi-frequently to pin down what I'm thinking about (though far more often as a fiction writer than as a critic, weirdly). Their existence, however, has led to a belief in a certain kind of viewer or amateur critic that if you can accurately catalog every element of a plot and pin it to a display board, you will have mastered it, dissected it, and robbed it of its power. Then you can move on to the next thing. Art is not to be engaged with; it is to be taxonomized.

This tendency has been combined with the work of YouTube channels like CinemaSins and any number of "bad movie" podcasts. Often, the critics whose work these folks are drafting off are vital, interesting voices, doing groundbreaking criticism in spaces where it hasn't always been practiced. But, again, you see a harsh but funny review of something on YouTube and wonder if, hey, maybe there's a way to simply catalog everything wrong with a movie...

What I find dispiriting about this isn't necessarily the existence of this kind of criticism – a little of it is probably inevitable and even necessary – but the ways in which it has infected every element of how many people talk about art, this is most evident when looking at how, too often, a person comparing a current work of art to an older one is attempting to invalidate the newer one, a tendency that has led to situations where a critic comparing one artwork to another (a vital part of our jobs) is seen as attacking one or the other in the process. I wrote a little about this for Vox in the midst of an Olivia Rodrigo "plagiarism" controversy, one that clarified a lot of my thoughts on these matters. (If you want to read this newsletter but at greater length and with more references to pop stars, click on the link!)

One of the failings of the modern pop culture landscape is the way internet platforms have tended to flatten all art into one thing: content. TV, movies, books, music, games — when we’re buried under an avalanche of them, an understandable anxiety to experience as many works as possible becomes evident. To be completely morbid about it, there are only so many more movies I can see, so many more novels I can read, and so many more TV shows I can make it through before I die. Shouldn’t I try to maximize the amount of stuff I consume in that time?

In a word: no. Even though criticism is my job, endless consumption runs the risk of reducing everything I watch to just another notch in the belt. I need to see a lot of stuff to write what I do, but watching too much ends up obscuring deeper themes or more nuanced readings in favor of surface-level qualities of plot and immediately noticeable flourishes. When all we see are those surface-level qualities, it becomes dangerously easy to miss the forest for a handful of brightly colored trees.

It might be fun for you to hold an artwork in contempt and shit all over it, and sometimes, those sorts of reviews are cathartic. But when you begin from the assumption that a work will suck, and it has to win you over, I don't know that you're doing the best writing. Criticism is a conversation, sure, but it's a generous one. Think of the art you criticize not as something to angrily interrogate but someone you haven't seen in a long time whom you'd love to get caught up with. Maybe they will be someone you no longer see eye to eye with. Maybe they'll make you extremely mad. But at least you tried. That's all anybody can do.

Consider becoming a paid subscriber: Running this newsletter is absurdly expensive, and by becoming a paid subscriber, you'll both help keep the newsletter online and keep posts like this free for those who can't afford to upgrade. But you'll get other stuff, too! Paid subscribers get access to comments, a weekly discussion post on Fridays, and occasional other special posts and features. There will be some other fun treats along the way. Click the button to learn more!

Three things: I've been into things this week, and here are three of them.

- My bio mom was here a week ago, and while we have a striking amount in common (DNA!), she loves audiobooks, and I dislike them. (Despite my enmity, we cast a surprising number of audiobook narrators on Arden.) Or so I thought. What I realized was that I've never properly given audiobooks a shot, and maybe they would be just the thing to listen to when visiting the gym. So far, I'm not a full convert, but I have to admit I'm really enjoying them as a conduit for romance. Currently, I'm making my way through The True Love Experiment by Christina Lauren (narrated by Jonathan Cole and Cindy Kay), chapter by chapter, and there's something about hearing a narrator describe what it's like to look at the heroine (or describe what it's like to be seen by the guy) that makes everything a little more visceral. Audiobooks! They might have something going for them here! (List your favs in comments!) (My birth mom recommends the audiobook for Trust by Hernan Diaz!)

- As a former South Dakotan, I have to recommend this essay by Garrett Bucks on visiting Mount Rushmore. Bucks writes a newsletter about being a white guy trying to better understand how white supremacy infects everything in America, and as such, he went to Rushmore for the first time, viewing the monument through that lens. What's even more interesting in this piece are his reflections on talking to people all over the country on his travels. An excerpt: "I can’t remember the last time I’ve had a meaningful conversation with anybody from either side of the political spectrum who actually feels optimistic about the current direction of our country. That’s not to draw a moral equivalence between those whose angst stems from naked assaults on human rights vs. those who are angry that drag queens exist and sometimes enjoy reading children’s books. It is notable, though. We’re all filled with dread, but it’s as if we’re afraid that if attempt to make sense of that shared ennui honestly, that somehow the center won’t hold."

- It's day 100 of the WGA strike, and the AMPTP still refuses to negotiate with us in good faith. If you see a writer today, give them a little hug. And if you just want to know how to help out, there are some great mutual aid opportunities linked here.

This week's reading music: "Ambulance" by TV on the Radio

Next week: Trauma and furniture.

Episodes is published twice a week, with an edition for all subscribers on Wednesdays and one for paid subscribers on Fridays. It's written by Emily St. James, who covers whatever she feels like writing about, but if you have suggested topics, please reply to the email version of this newsletter or comment (if you are a paid subscriber).

Member discussion