American film could use a little more J-horror in it

American horror looking to break clichés should borrow some ideas from Japanese horror films, writes Lily Osler.

Last year, I saw something that made me believe, however briefly, that American horror was finally starting to learn the lessons I’d long hoped it could take from classic turn-of-the-millennium Japanese horror films.

What I saw was a very brief scene in Longlegs, Osgood Perkins’ extremely divisive 2024 FBI horror-thriller. Right around the movie’s act one/two break, our protagonist, special agent Lee Harker, finds a terrifying life-sized doll beneath a dusty crucifix in the floorboards of an old house. In a sterile white room, a surgeon in scrubs stands over the doll as he explains to Lee that he’s found a stainless steel orb inside its head. “I’ve been calling it the brain,” he says, half-jokingly. The sphere is inert, but an ultrasound wand reveals a horrible noise emanating from within it. No one knows how.

It’s a quiet, still moment in a film that’s (at least ostensibly) concerned with men who commit family annihilation murders, made immensely creepier — and, importantly, far more uncanny — by the blasé manner in which the orb’s baffling nature gets shown off to both Lee and to the viewer. Without anyone in the film, at that point, saying as much, it communicates a clear and urgently horrific sense of something ancient and unknowable enigmatically contained within something entirely modern, complicating any safety you may have been feeling in rationality or logic or explanation. The tools of medical science can let you hear the screams of whatever cryptic, malign force is lying invisibly in wait inside that featureless orb, but they can neither explain it nor give you control over it.

I am generally a Longlegs skeptic; I’m certainly more of one than Emily. I think the movie has interesting ideas it wants to express (about patriarchal violence within the family, in particular) but that it lacks either the clarity to get those ideas across effectively or a sufficiently interesting surreal imagination to let me believe in its dream logic. But one thing you definitely can’t accuse Longlegs of is bowing to indie horror trends. Unlike many of its bad middlebrow contemporaries (The Invisible Man, Men, The Woman in the Yard, the Halloween requel trilogy, arguably The Night House, Smile 2), it engages with a real trauma/social issue without beating you over the head with “the monster represents this particular trauma/social issue.” It approaches patriarchal violence both directly and obliquely, as an ancient evil reasserting its power over and over in a world that wants to have moved past it. For all the things about the movie that I find silly at best, it, nonetheless, often manages to feel like a haunting both on and off the screen, as though it (or at least its better images and ideas) might just follow you home.

In all these ways — in the tiny particularities of the ultrasound scene and in the broad strokes of how it approaches its themes — Longlegs is deeply (and explicitly) indebted to the Japanese horror film boom of the late Nineties and early Aughts, a period I'd define as spanning roughly from Ringu's release in 1998 to Koji Shirashi's mid-2000s output ("Y2K J-horror" hereon out for concision). Longlegs doesn’t go quite far enough in its J-horror emulation for my taste, of course, but it’s closer to finding a way to make American horror that follows the principles of Y2K J-horror than just about any film I’ve seen. And as we come up on 25 years since the peak of the J-horror boom in America, I’m hoping that even more young filmmakers influenced by its structures and precepts will make their mark on American horror cinema.

But what would American J-horror (A-horror? No, absolutely not) actually look like in practice? Most likely, not very much like Y2K J-horror at all. Japanese horror, like American horror, is pretty culturally contingent; there’s a reason none of the American J-horror remakes (save maybe the Naomi Watts Ring) manage to pull off transferring Japanese stories wholesale to an American context.

Rather, what I’d love to see — what I think American horror could really use, given its clumsy last few years — would be an American horror cinema that uses the principles of Y2K J-horror to craft movies that are lived-in, specific, and terrifying. With the caveat that I'm a fan but by no means a subject matter expert, I've identified four common structural conceits I've seen across Y2K J-horror films that fit this bill.

Become a paid subscriber: You'll get access to two weekly newsletters only paid subscribers receive, the Episodes Discord, and almost a decade of archives. Sign up for as little as $5/month below!

The past usurping the present

This is, perhaps, the most famous tenet of the J-horror boom, and for good reason! You’d be hard-pressed to find a movie from that wave whose evil does not come from the sins of the past. Many of the most famous J-horror monsters, from Ju-on: The Grudge’s Kayako to Ringu’s Sadako to Dark Water’s Mitsuko, are vengeful ghosts, but you can find everything from ancient deities-slash-possibly-aliens (Kagutaba in Noroi: The Curse) to new practitioners of obscure and murderous hypnosis techniques (Mamiya in Cure). Occasionally, you’ll find a J-horror villain that emerges from diffuse ills of the past (the internet ghosts in Pulse), but much more frequently the monsters are born from a specific, clear, bounded act of past evil.

(It's worth noting that this means J-horror’s approach to evil — as an explicable consequence of past monstrosity — matches up more closely with the less-reputable branch of American horror film descended from Friday the 13th than with the traditionally “smarter”/more philosophical branch descended from Halloween, but that’s another essay!)

What’s particularly important in Y2K J-horror is that the past evil is rarely asserting itself upon a present that in any way resembles the past. Sadako, famously, died on a farm on a still-rural island decades ago but now haunts the VCRs and cordless phones of Tokyo. Pulse’s ghosts, driven mad by the eternal loneliness of the afterlife, find unexpected kinship in Very Online teens whose perpetual internet connections only serve to isolate them further from one another and themselves. Kagutaba is angry because the village that once worshiped him is now behind a dam and beneath a lake. Its residents have spread throughout the countryside and become permanently severed from their former appeasement rituals. Even when only a generation separates the evil-creating violence from the movie’s setting, the world the monster once knew has been irrevocably transformed.

I recoil a bit when people talk about Americans as inherently forgetful of the past, mostly because that sort of simplification reduces “Americans” to “straight white Americans,” ignoring the tightly-held memories of Black and Indigenous Americans in particular. But there is some truth in the cliché, particularly since American horror film is still disproportionately made by, well, straight white people. The mainstream white American sense of the US as existing outside of history and contingency could stand a few movies in which the many, many evils of this nation’s past claw through the thin sheet of the present in a more thoughtful manner than the old, offensive "ancient Indian burial ground" trope.

Subtle, specific literalism

Another distinguishing feature of Y2K J-horror is that the way the landscape has transformed is almost always culturally and temporally particular. It’s tempting, as an American in the 2020s, to read, say, Pulse as a film about the Internet’s isolating effects writ broad, but, like many other J-horror films, the way it views technological change is clearly informed by the particularities of Japan’s rapid uptake of cutting-edge communications technology after World War II and the country’s malaise after its Nineties economic crash. This specificity, evident in the lived-in way characters in Pulse interact with the Internet, helps keep the movie from feeling dated in the way a quarter-century-old Internet horror movie very easily could.

Likewise, Y2K J-horror gets much of its power from allowing the social issues its monsters illustrate to be highly specific. Kagutaba’s shrine was drowned in an attempt to electrify the countryside; Kayako was murdered in an act of femicide by her husband, who suspected that she was having an affair; Sadako, another femicide, died at her parents’ hands, in no small part for being neurodivergent. In all these cases, the details really do matter. They lead to films that feel more relevant and more incisive than anything vaguely “about trauma” ever could.

It’s also worth noting that, in the case of every film mentioned above, a monstrous force representing a societal problem is never just an allegory for that societal problem. Pulse is literally about the lonely ghosts of the past identifying with lonely Internet users in the (then-)present. It’s a blunt sort of thematic work, but I’ve found it’s often more effective than “x represents y” allegorical horror, in no small part because it doesn’t have to waste time handholding its viewer to understanding what its themes are and how they work.

Present ways of seeing revealing an uncanny past

The first thing I clocked about that scene in Longlegs that made me think about J-horror was the doctor’s affect as he examines the doll. He’s direct, removed, casual, curious about the eldritch forces he’s investigating but only slightly. Or, to put it another way: He’s being a modern forensic physician, even when confronted with ancient knowledge beyond the purview of modern science.

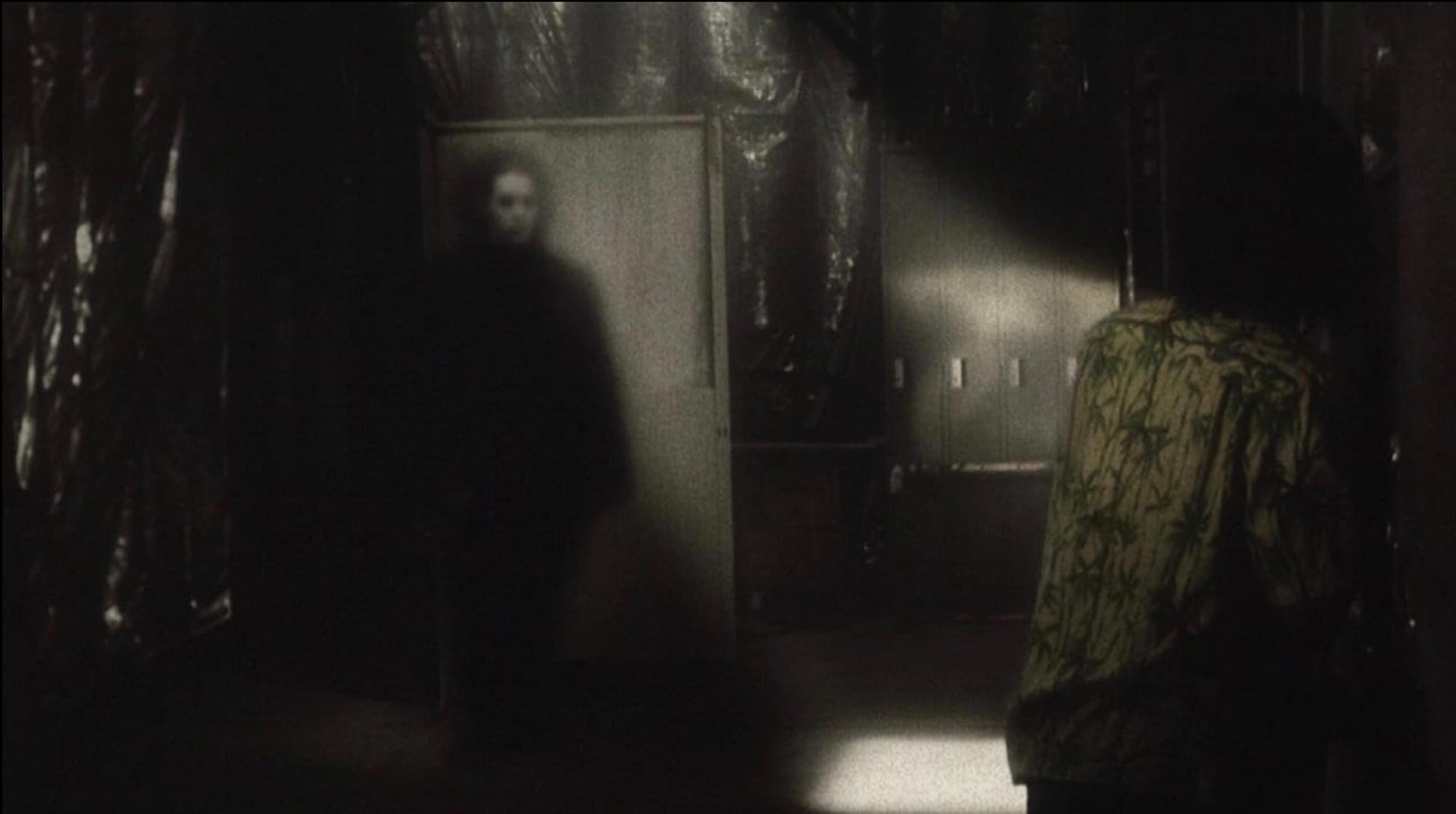

This sort of contrast — the evils of the past, seen through the detached, alienated lenses of the present — is maybe J-horror’s greatest aesthetic contribution to modern horror. The most famous example of it, probably, is the neutral plastic-and-glass case of the television in Ringu framing the infectious, wrathful evil of a murdered child, but you can see it everywhere in the genre: in the moments in Noroi where Kagutaba’s face erupts in glitch effects on a docudrama’s tape, in the sterile police station in Cure where Mamiya demonstrates his hypnotic gifts. This juxtaposition even influences the way the camera moves in J-horror films, as in this astonishing static shot from Pulse in which we the viewers see a ghost for the first time. It’s a terrifyingly uncanny effect, and one that emphasizes both the persistence of past evils and the particular kind of past evil a given film is choosing to focus on.

Ritual and knowledge are an insufficient solution

Something my wife told me years ago that I’ve been pondering since is that J-horror films are shaped fundamentally differently than most American horror films; the plot engine of most American horror films is survival, but the plot engine of J-horror is almost always investigation. American horror protagonists search for knowledge in isolated spurts, sure, but they rarely spend multiple scenes traveling to the university archives or village historical centers that J-horror protagonists love to frequent, always searching for the historical context of the evil they’re fighting.

In many (not all!) Y2K J-horror films, these protagonists do actually solve the mysteries they’re investigating, whether it’s realizing that Sadako’s buried at the bottom of a well or finding a video of the rituals that might put Kagutaba at peace once again. They do exactly what they’ve been told they need to do to end the curse, which usually involves righting, in some way, the historical wrong the evil presence emanates from. They believe that they’ve put things right.

And then, inevitably, the evil reappears. Sadako crawls back through the TV screen after seven days, hungry for the life of the person who thought they’d finally put her spirit to rest. It’s a deflating gesture, a purposeful denial of the catharsis we thought we’d felt a few scenes earlier, a subversion of the trauma plot premise that the revelation of past harms and a symbolic gesture to set them right will fix everything. While it’s hard not to find this sort of ending depressing, it’s also a meaningful way to honor the depth of the past horrors that haunt these films, to give them the weight they deserve. Finding Sadako’s bones is a nice thing to do, but it won’t un-kill her.

In an American horror landscape in which the trauma plot is cloying and unavoidable, it would be unbelievably refreshing to see filmmakers start to embrace these sorts of downer endings, moments that remind us, in a world where the past feels either impossibly distant or magically fixable, how little control we really have over the evils that precede us.

A Good Song

The free edition of Episodes, which (usually) covers classic TV and film, is published every other Wednesday, and the subscriber-supported edition of Episodes, which covers more recent stuff, is published every Friday. Paid subscribers also have access to the weekly Monday Rundown. Our editor-in-chief is Emily St. James, and our managing editor is Lily Osler. If you have suggested topics, please reply to the email version of this newsletter or comment (if you are a paid subscriber).