1984: the greatest year in American pop music

From Michael Jackson to Prince and from Bruce Springsteen to Huey Lewis, the year rang with enormous, amazing hits.

(Each week, I’m publishing a new pop culture essay from a freelancer. Remember: Your subscription fee helps me pay these freelancers for their efforts! This week: Sergio Lopez on the greatness of American pop music in 1984.)

1984 was the greatest year in American music history.

As the swelling waves of commercial forces, critical acclaim, and musical production crested, cheap and broadly available technology meant that Americans across the country were able to listen to the same things as never before. Just five mega-albums dominated the year — a feat that had never happened before, and will probably never happen again.

Each of these albums also tells an overarching story about the country, a story written by artists and producers, the hand of commerce, and the forces of fate. Here’s what each of them tell us about the landscape of American culture — then and now.

Thriller, Michael Jackson (Jan. 7 - Apr. 14)

Michael Jackson’s Thriller was released in 1982, when it could be heard from boomboxes and Walkmans around the country. Its surging beats and wicked guitar licks still dominated in 1983. And in 1984, it rang in the new year, holding its spot atop the charts.

Yet despite the mass appeal of one of the most infectiously danceable albums of all time, there’s a dark undercurrent of paranoia and violence underlying the album. The title song pays explicit homage to horror, while the titles of “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’” and “Beat It” are as much a warning as they are an invitation to dance. And then there’s “Billie Jean,” either a story of obsessive delusion or of a man running out on his responsibilities — delicious ambiguity, alongside one of the greatest dance beats in musical history.

As a child I was obsessed with the line, “For forty days and forty nights, the law was on her side …” It carries biblical resonance — the amount of time the earth was inundated during the flood in the Old Testament; the amount of time Jesus Christ was tempted by Satan in the desert in the New. It felt like the line was the key to unlocking the song, itself a story of violence and temptation. Was 40 days and nights the length of a trial? Time spent in jail, or in the court of public opinion? Deliriously, I imagined it was the amount of time the narrator and his erstwhile lover spent on the dance floor, locked together in a dance of obsession, desire, and paranoia.

The dark and violent possibilities of the album reflected the insecurities of Jackson’s own childhood, of the abuse at the hands of his father, and of his ensuing ambition to make the greatest pop album in musical history. The result is all-American: violence as allure, a darkness that you can’t help but dance to.

Footloose: Original Soundtrack of the Paramount Motion Picture, Various artists (Apr. 21 - Jun. 23)

Since Martha and the Vandellas sang “Dancing in the Street” in 1964 — sounding as much like an anthem of free-wheeling revolution as it did a dance track — other artists had invoked the call to take to “the street” to reflect their changing times. In 1968, as the hope of the first half of the decade curdled into senseless violence in its latter half, Mick Jagger sang that “the time is right for fighting in the street.” In 1978, amid stagflation and recession, Bruce Springsteen sang forlornly of hard-up characters going “Racing in the Street.”

1984, however, brought the Footloose soundtrack and with it Shalamar’s “Dancing in the Sheets.” A phrase that had begun as a communal call to action became a private invitation to a different kind of action. With the 1960s in the rearview mirror, personal revolution and expression was at hand — and at the level of a mass audience.

The soundtrack to Footloose, the mega-hit film starring Kevin Bacon, is also wildly derivative. “Dancing in the Sheets” takes its cue from Prince’s “1999,” the instrumental introduction to Kenny Loggins’s “I’m Free” sounds suspiciously like “Beat It,” and the grab bag of genres on the album are a pretty good synthesis of the charts as a whole that year.

But who cares if it’s derivative? None of these concerns take away from the sheer enjoyment — and fun — of the album. Sometimes, you just need to dance.

Sports, Huey Lewis and the News (Jun. 30)

The chart trajectory for 1984’s top albums reads like a visual gag — four of the most dominant albums in music history. Then, sandwiched in between, there’s one week for Sports. That’s not a slight against Huey Lewis and the News, whose album slowly but steadily clawed its way up the charts before breaking into the top spot.

In fact, Sports is a deeply enjoyable album, one that sounds best blasting at full volume on a hot summer day as you’re driving down the freeway. Two years later in 1986, Lewis would sing that it was “Hip to Be Square.” Sports is firmly in the same tradition. Indeed, Sports’ third track, “Bad is Bad,” with its playful chorus reminding us that “cool is a rule, but, sometimes, bad is bad,” can be read as a pre-emptive musical rebuke to Jackson, who in three years would release Bad, his follow-up to Thriller. (“Bad Is Bad” and Bad have nothing to do with each other, of course; Huey Lewis does not possess psychic powers.)

Huey Lewis and the News came from a different musical tradition than Jackson, one steeped in honky-tonk country and rockabilly as much as it was in rock and pop. As if to drive the point home, Sports ends with a cover of country crooner Hank Williams’ “Honky Tonk Blues,” which had been a major hit — in 1952.

Born in the U.S.A., Bruce Springsteen (Jul. 7 - Jul. 28)

Neatly picking up the baton from the closing track on Sports, Springsteen quoted Williams when he sang, at the end of the first song on Born in the U.S.A., which was also the title track: “I’m a long gone daddy in the USA.!” (Williams sang, “Well, I'm a long gone daddy, I don't need you anyhow.”) What was a tale of personal domestic woe for Williams became, in Springsteen’s retelling, the personal not just made political but writ large. “Born in the U.S.A.” is all about the heartbreak that comes from betrayal by a country you once believed in and sacrificed for.

The path to the release of Born in the U.S.A. was a fraught one. Many of the actual studio recordings dated back to two years prior, and some of the songs, like “Downbound Train” and early iterations of what was eventually shaped into “Born in the U.S.A,” had their roots in the 1970s. Everyone who listened to the recordings knew Bruce had a mega-hit album on his hands — if he would only let go and release it. He did so reluctantly, knowing the limitations of commercial appeal and success, though also the possibilities they opened up for communicating to an audience. With the singer’s biggest ever singles — smash hits like “Dancing in the Dark,” “Glory Days,” and “I’m On Fire” — the album ensured his place in the upper echelon of pop stardom.

So when Springsteen released the single “Born in the U.S.A.” — the core of a hard-hitting protest song wrapped up in the shiny shell of a pop mega-hit — it’s hard to imagine that he was entirely blindsided by the confusion that followed its release, when the song became an unofficial national anthem. George Will sang Springsteen’s praises, and at a campaign stop in New Jersey, Ronald Reagan told his audience, to rapturous applause: “America’s future rests in a thousand dreams inside your hearts. It rests in the message of hope in the songs of a man so many young Americans admire—New Jersey’s own, Bruce Springsteen. And helping you make those dreams come true is what this job of mine is all about.”

The speech was one small step along the way to Reagan scoring one of the most crushing landslide victories in U.S. presidential history. This by the man who four years earlier had started his first presidential campaign at the site of a racial lynching, promising to fight for the dog-whistle of “states’ rights.” In a mass communication culture, whether politics or media, Reagan or Springsteen, differences can be elided. Audiences can receive the message they want to hear. It’s why I’ve often wondered, listening to Reagan’s speech where he quoted Springsteen’s mega hit: Whose dreams was he making come true?

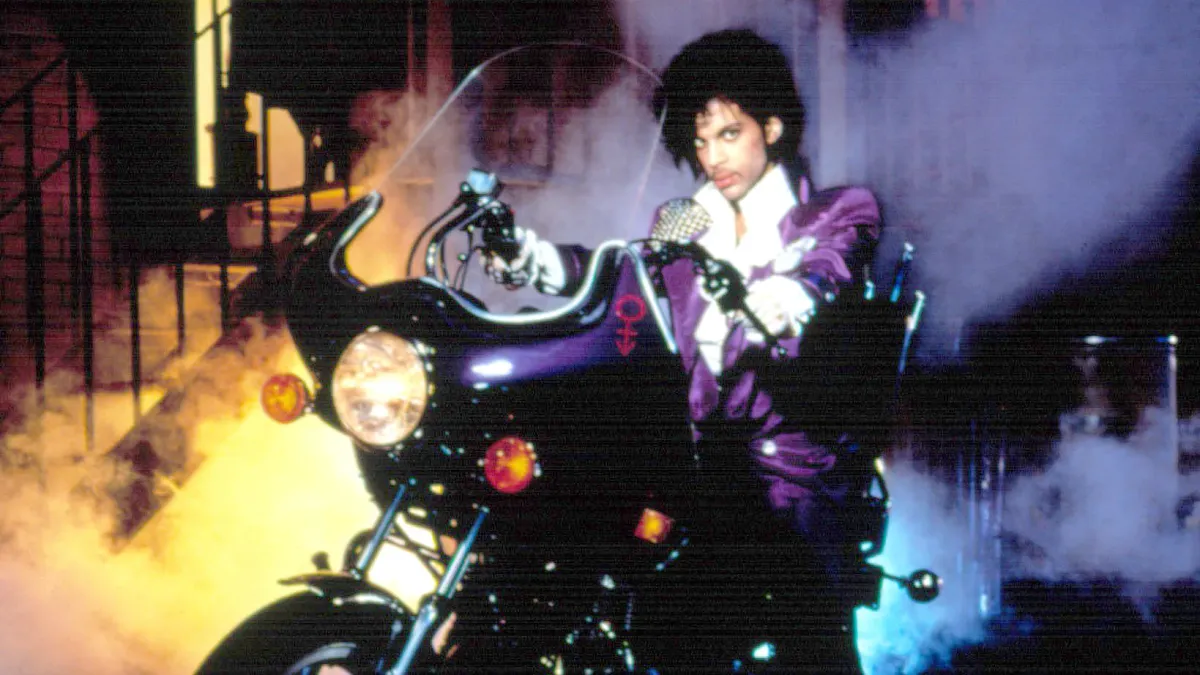

Purple Rain, Prince (Aug. 4 - Dec. 29)

On “I Would Die 4 U,” Prince sings: “I am something that you’ll never understand.” The claim was just as true for his bending the lines of gender and sexuality, though, as it was for his fraught relationship to race.

One place that remains just as segregated in 2021 as it was in decades past are music genre classifications. Walk into almost any record store in the country or browse Spotify’s playlists and you’ll easily find “Rock” and something labeled along the lines of “Funk/Soul.” But compare the musical contents of each and you’ll find that they’re divided not by musical style or influence but by race. Musical pioneers like Sly Stone, James Brown, Stevie Wonder, and, yes, Prince — polymaths who both influenced and were influenced by the “rock” genre — will nonetheless be relegated to a separate section of the store.

Prince foresaw and feared this fate. On the eve of his major label debut, he told a Warner Bros. executive, “Don’t make me Black.” It wasn’t a commentary on the color of his skin so much as a recognition of the fact that music has always been segregated commercially and on the charts, whatever the reality of its audience’s actual listening habits. Likely because of this, Prince’s PR team for years pushed the fiction that he was biracial.

But with Purple Rain (and the feature film it was technically a soundtrack for), Prince was utterly dominant on the charts in 1984, and he held the top spot on the Billboard Album charts for longer than any artist that year.

With Purple Rain, the charts came back full circle to Thriller — two of the most talented Black performers in pop culture history, rivals; each playing homage to the Black performers who had come before them but who hit a ceiling to their financial success despite lasting influence. Jackson was raised a devout Jehovah’s Witness, going door to door as a child, and Prince converted to the religion went door to door himself after reaching the heights of success. Each of these artists had a complicated relationship to race and attempted to transcend it in their work, each in turn succeeding and failing to do so in different ways.

Nonetheless, despite their complex relationships with race, for nearly three quarters of 1984, the album charts were dominated by two Black artists who were utterly at the top of their game and who appealed to the American monoculture at its absolute zenith.

In fact, all of the top-charting albums that year, to differing degrees, cut across racial, ethnic, class, and gender lines, as everyone, it seemed, blasted the same music from boomboxes and danced to it on club floors. It was before the many genres they spanned splintered into not just sub- but sub-sub-genres. Each of these albums told a different story about America and how it perceived itself, and as each hit single went out along the airwaves, was further reinterpreted and recontextualized by listeners in turn.

It was the biggest year in American music history.

Sergio Lopez is a historian, cultural critic, and City Councilmember for Campbell, CA. You can read more of his work at sergio-lopez.com/work and follow him on Twitter @lopezforca.

Episodes is published three times per week and edited by Emily VanDerWerff. Mondays feature her thoughts on assorted topics. Wednesdays offer pop culture thoughts from freelance writers. Fridays are TV recaps written by Emily. The Wednesday and Friday editions are only available to subscribers. Suggest topics for future installments via email or on Twitter. Read more of Emily's work at Vox.